What would a fashion industry dominated by oligopolies look like? A new set-up that would solve some problems and create many more

Index

1. A New Paradigm for Luxury

2. Like in the '90s?

3. Fashion Like Tech

4. To Each His Own

5. Who Could Be the "Fantastic 5"?

6. But Do We Want Such a Luxury?

7. Takeaways

1. A New Paradigm for Luxury

The crisis that fashion faced in 2025 was not just a simple sales collapse. More and more, among new M&A, commercial deals, and distribution models, we are noticing that the main effect of this collapse has begun to rewrite the way the fashion business works at its most basic level. Think about how LVMH is lightening its brand portfolio by getting rid of Stella McCartney and (it's said) of Marc Jacobs. Think about the curious, some would say suspicious slowness with which the deal between Prada and Capri Holdings for Versace is unfolding. Think about how the king of independents, Armani, has written in his latest will the order to welcome external investors, to break the monolith that the brand had become.

Think especially about Kering, the true epicenter of this crisis, which to save itself has called in a new CEO, Luca De Meo, precisely to review without unnecessary preconceptions the entire functioning of a gigantic luxury ecosystem, and identify its critical issues. From the latest news we receive, the critical issues were many: Bain & Company and BCG have been summoned to conduct a "diagnosis" of the fashion department, the dependence on creative directors has already been declared the main hole in the hull of the group, employees of the unprofitable McQueen have been cut, and according to Lauren Sherman the brand itself might soon be sold to simplify things and, above all, Kering Beautè has been sold to L’Oréal for 4.7 billion euros.

This very sale is not just a financial move to lighten the group's debt but seems to represent the first "trumpet blast" that will open a new trend in managing luxury empires: the linearization and consolidation of the sector after years of absolute financial bulimia. Empires that are too big split up, herds that are too populous slim down, and after years of tumultuous growth, businesses must become more efficient and agile so as not to collapse under their own weight. And the signals we see in the industry, combined with the shrinking of the luxury customer base, now focused on the ultra-rich; the emptying of the intermediate market segment now colonized by fast fashion; and a slow and cumbersome model like that of fashion all indicate that a new era is about to begin.

2. Like in the '90s?

@ornelgamag Did you know that LV and Dior are part of the same company? Let me explain you a bit about the leading Luxury Fashion conglomartes… #fashionnews #tiktokfashion #lvmh #kering original sound - ornelgamag

In some ways, today's situation reprises the late '90s scenario in which LVMH and Kering thrived: tons of historic brands now old and tired, drained by wild licensing deals made to put money in the pockets of founders or heirs. An old ecosystem onto which the new super-predators emerged who conceived the idea of a luxury industry consolidated into a series of conglomerates capable of offering a platform for dying businesses, too late and too tired for the new millennium.

This is how the Arnaults and Pinaults of this world built their fortunes: by merging brands under the same big name, giving each a more or less common production and distribution base, corporatizing what were old-school family businesses, and cutting off the thousand silly licenses to keep merchandise, prices, and positioning under control.

An excellent model that today needs renewal: the market is once again overpopulated with superfluous brands, split between those that churn billions and others whose revenues are much more mediocre, all the big names produce in the same factories and expand into the usual fields of perfumery, furniture, real estate and hospitality. A waste of resources, a dilution that now must narrow again to leave only the true essence. In short, is fashion about to become a big oligopoly?

3. Fashion Like Tech

The five macro-areas into which the global fashion market is dividing today are that of traditional luxury, that of mid-tier brands that thrive through e-commerce and social ecosystems, the world of "conventional" fast fashion that is moving ever more toward the middle market, ultra-fast fashion of brands like Temu, and finally, the emerging market for wearable tech that is taking its first steps through the alliance of Meta and Luxottica. Such coagulation into a system of pseudo-oligopolies is already happening in the world of beauty and eyewear.

The situation recalls the Silicon Valley of the 2010s: too many small and powerful kingdoms always end up, one way or another, consolidating by merging into each other, as happened with the Big Tech of various Apple, Microsoft, Alphabet, Amazon, Tesla, and Meta, among others. Large companies that slowly acquire the smaller ones, centralizing social media, search engines, telephone services, and so on. It remains to be seen if it could happen: certain businesses like eyewear are too profitable to be handed back to EssilorLuxottica, Marcolin, or the Safilo Group (Kering's eyewear division is the healthiest part of the business at the moment), but many others could be reabsorbed into each other.

LVMH in market to sell its 50% stake in Fenty Beauty. With sales at $500m+ the rumored sale price is $2B.

— Fan Bi (buy/ advise $5-50M brands in special sits) (@lifeofbi) October 29, 2025

The behind-the-scenes story is Kendo, LVMH’s secret beauty VC.

Kendo = the “can-do” incubator born inside Sephora.

It creates tests scales exits beauty brands.… pic.twitter.com/EfMyU8qzMO

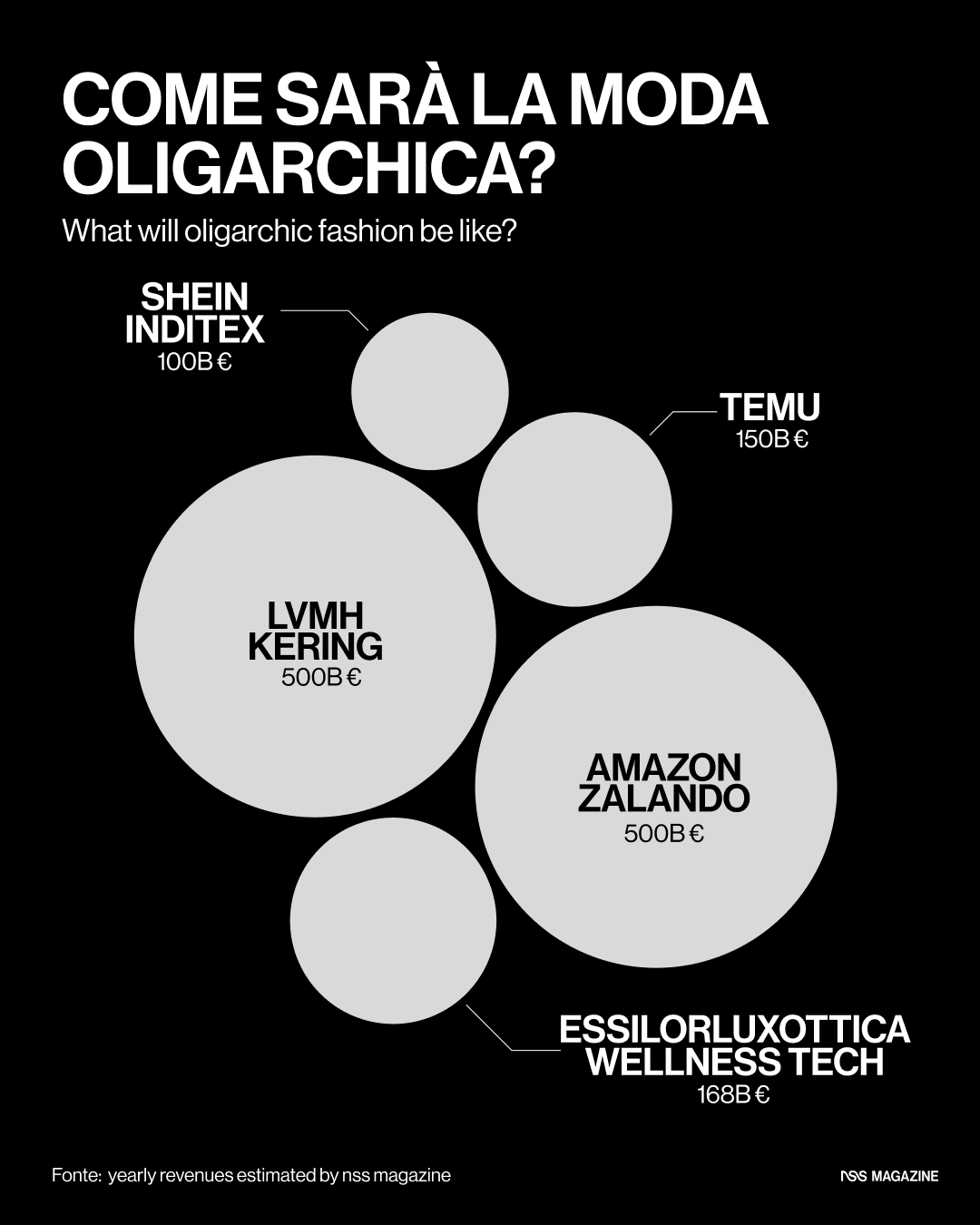

If it happened, the lifestyle sector (a mix of fashion, e-commerce, wellness, and digital) would evolve into an oligopoly dominated by five giants, the result of mergers and acquisitions that would reduce fragmentation to a market controlled 80% by a few players by 2030. The outlined scenarios? LVMH swallowing Kering, Amazon absorbing Zalando, Shein allied with Inditex, Temu as a lone wolf, and a wellness-tech hub led by EssilorLuxottica. Of course, this is all speculation, but the hypothesis echoes real trends, like Amazon's historical interest in Zalando or LVMH's serial acquisitions through L Catterton, and captures the zeitgeist of an industry on the brink between tradition and revolution.

In their time, the "Fab 4" of Silicon Valley consolidated 70% of the digital market through predatory acquisitions: think of Facebook swallowing Instagram or Amazon absorbing Whole Foods. Similarly, hybrid luxury, which would include all the AI and wellness ramifications of fashion, would require giants to invest in innovation. McKinsey estimates that by 2030, 80% of luxury sales will pass through digital channels, with AI personalization as the competitive key. Yet, fragmentation persists: over 100 independent brands struggle against complex supply chains and rising costs, while fast and fierce realities like Temu (grown 200% year-over-year, with 300 million users) and Shein (which totaled 10 billion in revenues in 2025 and is increasingly infiltrating Europe eroding fast fashion market shares) democratize lifestyle at rock-bottom prices.

4. To Each His Own

@ornelgamag Did you know that LV and Dior are part of the same company? Let me explain you a bit about the leading Luxury Fashion conglomartes… #fashionnews #tiktokfashion #lvmh #kering original sound - ornelgamag

In this scenario, the idea of consolidation makes sense because, thanks to the "glue" of licenses, competition turns into synergy. By selling its cosmetics department to L'Oréal, which already controls 20% of the global beauty market, Kering steps out of an expanding segment, leaving the field to a super-predator that could integrate these licenses to launch exclusive lines and scale in Asia. Meanwhile, Kering lightens its operational load while maintaining profits through lucrative licenses.

When Tom Ford sold his empire a few years ago, the business was even split up: beauty and fragrances went to L’Oréal while clothing stayed with the Zegna Group, already a licensee of Ford. Instead of a new owner managing a new business, each part of the company ended up in the hands of a specialist who integrated it into their core business, minimizing margins of error and maximizing those of profit. The invisible hand of the market redistributes assets and resources according to a principle of affinity – it is therefore logical to think that a mega-company that deals only with clothing and accessories functions better than one that has to handle it together with beauty, hospitality, eyewear, and so on, diluting its resources and exposing itself to potential risks.

And in the face of advantages like the integration of global supply chains and the linearization of many processes that today happen in parallel with considerable waste of resources, there are equally risks. A fashion dominated by oligopolies not only risks becoming pure creative slop (one of De Meo's principles, for example, is to rely 80% on market analysis rather than the fallible flair of a creative director) but in general the formation of monopolies on supply chains could lead to unjustified price increases for consumers and a compression of opportunities for small and medium enterprises, which risk being excluded from the dominant distribution circuit.

Not to mention the open war that half the world's nations would wage on the oligopoly. On the other hand, the opportunities could be equally interesting, like accelerated investments in environmental sustainability that adopt large-scale circular practices, such as material recycling and digital traceability of supply chains through blockchain. If so, consolidation would not only strengthen supply chains against potential global crises (which are always around the corner) but create the premises for transnational collaborations for shared ethical standards, long one of the utopias of activists.

5. Who Could Be the "Fantastic 5"?

In a hypothetical world where fashion were dominated by oligopolies capable of controlling 80% of the global market valued at 450 billion euros in 2024 according to Bain & Company, everything would be different, from supply chains to accessibility but with the serious risk of total creative leveling. Imagine a unified block of brands, like a hypothetical merger between LVMH and Kering, that absorbs 30% of the world's supply in a colossus worth over 500 billion euros, unifying supply chains for 15-20% cost cuts and pushing expansion into emerging markets like India or Brazil.

Here, the potential for synergies in innovation and sustainability would clash with the danger of a monopoly that stabilizes prices but crushes the remaining 60% of the market, namely any independent and small medium enterprise, creating a standardized and less authentic offer. Similarly, a "block" that merges Amazon and Zalando together could generate an e-commerce giant worth 500 billion euros annually, integrating same-day logistics in 20 countries with augmented reality for immersive shopping, capturing Gen Z which represents 40% of online luxury consumers; the opportunities for AI personalization for hybrid outfits would be immense, but risks of antitrust investigations under the EU's Digital Markets Act could impose concessions, centralizing data and homogenizing the experience to the point of diluting the European heritage against rivals like Temu and Shein.

Precisely for this purpose, if Shein and Inditex were to become a single entity, it would unite the low-cost market with agile supply chains for an ecosystem worth over 100 billion dollars annually. Here too, the opportunities related to the circular economy and the conquest of 20% of the middle segment market would push toward a merger or integration of different models like combining low-cost fast-fashion with more ethical and medium-quality elements. But the oligopoly would risk uniforming ethics and quality as well as destroying quality.

In this scenario, Temu and its 292 million global monthly active users would remain a unique block, while EssilorLuxottica with wellness tech could form a visual hub worth 168 billion dollars, controlling 20% of the eyewear market and growing exponentially in the wearable tech market, integrating AI like in Ray-Ban Meta (which already sold 1 million units in 2024) for the definitive union between the fashion and health industries. The potential for personalized fitness monitoring would be revolutionary, but risks of oligopoly on health data in the hands of AIs would be a regulatory, bureaucratic, and ethical nightmare. In this scenario, the idea of an oligopoly promises scale for innovation, but presents us with the dystopian vision of a homogeneous luxury that would betray the very premises of the luxury concept.

6. But Do We Want Such a Luxury?

The ultra-utilitarian mentality that is beginning to emerge with the first "remedies" envisaged in De Meo's plan for Kering is not illogical. The CEO has widely praised Inditex for the agility of a mass-market-driven model that depends only literally 20% on the authorship and creative vision of the creatives who created the narrative on which the entire business rests in the first place.

Of course, in the history of fashion, there is a tendency to forget that behind every successful brand there is not only a visionary designer but also a businessman who makes the numbers add up: for decades, fashion has been divided between the Valentino and Saint Laurent and the Giammetti and Bergé. Of course, over the years both brands, despite the glory achieved, ended up in debt and put up for sale to enter the conglomerates that today dominate the market which, in turn, have already transformed the identity of founders and designers into a kind of enamel to apply to every imaginable product category regardless of narrative plausibility. In this sense, the change wanted by De Meo (and the more general consolidation of luxury it implies) sanctions an impoverishment that has already widely occurred.

The question thus becomes: can luxury survive without its narrative? Can luxury become totally industrial and do without its authors, with their mistakes and strokes of genius? If in a hypothetical future every luxury brand were just another facet of a single, colossal macro-organism, what would be the criteria for preferring one brand over another? And without competitiveness in the sector, with the cost-cutting mentality typical of today's management, who assures us we won't see fashion transform into a glorified version of Uniqlo? The challenges of a fashion dominated by oligopolies are all here: those who want to grow will have to efficientize to death, those who want to maintain the human dimension of luxury will perhaps instead have to degrow. We, as usual, will end up paying.

Takeaways

A New Paradigm for Luxury: The 2025 crisis has accelerated mergers and sales in fashion giants. LVMH is selling Marc Jacobs for about 1 billion dollars, while the Prada-Versace deal has received EU approval and will close by year-end. Armani has stipulated in his will the sale of a 15% stake to investors like LVMH or L'Oréal. Kering, under the new CEO Luca de Meo, has tasked Bain and BCG with reviewing the model, with cuts to McQueen and the sale of Beauté to L'Oréal for 4.7 billion euros – a signal of consolidation to reduce debts and focus on the essentials.

Like in the '90s?: Today, like at the end of the '90s, luxury is fragmented by exhausted brands and inefficient licenses. Back then, Arnault and Pinault created empires by unifying production and distribution, corporatizing families, and cutting waste. Now, with overpopulated markets and dilution into sectors like beauty and hospitality, a similar renewal is needed: narrowing resources for efficiency, transforming fashion into a leaner, more agnostic oligopoly.

Fashion Like Tech: The fashion market divides into five poles: classic luxury, digital mid-tier, fast fashion middle-market, ultra-fast like Temu, and wearable tech via Meta-Luxottica. This echoes the Silicon Valley 2010s, where Big Tech centralized 80% of the digital with predatory acquisitions. By 2030, lifestyle could be dominated by five giants at 80% of the market (1.48 trillion euros in 2024, per Bain), with scenarios like LVMH-Kering or Amazon-Zalando – speculative, but rooted in real trends.

To Each His Own: Licenses turn rivalry into alliances, like the Kering Beauty sale to L'Oréal (20% global market), which integrates to scale in Asia while Kering collects royalties. Similar to the Tom Ford split: beauty to L'Oréal, clothing to Zegna, to maximize profits with specialists. Advantages include unified supply chains and less waste; risks are diluted creativity (De Meo aims 80% on data, not flair) and monopolies that raise prices, exclude SMEs, and attract antitrust.

Who Could Be the "Fantastic 5"?: In an oligopoly controlling 80% of the market (450 billion euros estimated by Bain for 2024), LVMH-Kering would unite 30% of supply, cutting costs 15-20% and targeting India-Brazil, but risking standardization and crushing independents. Amazon-Zalando would create e-commerce worth 500 billion with AI for Gen Z (40% luxury online), exposed to EU rules. Shein-Inditex would found low-cost and ethics for 100 billion, uniforming quality. Temu would stay solo with 417 million active users (Q2 2025, +68% YoY). EssilorLuxottica would lead wellness-tech worth 168 billion, with Ray-Ban Meta (1M units 2024), but with privacy data dangers.

But Do We Want Such a Luxury?: De Meo praises Inditex for its agility (only 20% on creativity), prioritizing data over visionaries. History shows that behind designers like Valentino or Saint Laurent were managers like Giammetti or Bergé; today, conglomerates dilute identities into "enamels" for every product. This consolidation impoverishes narrative luxury: can it survive without authors and their errors-geniuses? In a macro-organism, how to distinguish brands? Efficientism risks turning it into premium Uniqlo, pitting growth (fierce cuts) against human degrowth – and consumers will foot the bill.