What does anonymity mean to Maison Margiela? Now that the brand has chosen Miley Cyrus as its ambassador, there seems to be a change on the horizon

“Of course I like Martin Margiela,” Alexander McQueen once said to The Independent. “I’m wearing him right now. His clothes are special for their attention to detail. He thinks of everything, the cuff of a jacket, the structure of the armhole, the height of the shoulders. I think it’s mainly about cut, proportions, and shape, simplicity, and sobriety. His clothes are modern classics. I don’t know any woman who doesn’t have at least one Martin Margiela piece in her wardrobe.” When McQueen spoke, Martin Margiela was still at the helm of his brand, which he left in 2009 when the ambitions of the OTB group became too vast for the kind of project the Belgian designer had in mind, and his myth was still fueled by his radical pursuit of anonymity.

For years and years, Martin Margiela’s anonymity was not just a style but a reaction against the commercialized fashion industry of the 1980s, when the myth of creative directors and the cult of their personalities began to develop in Italy and then in France. Today, things have changed significantly: Maison Margiela has become a major international brand and has had to find a more sustainable balance to survive in today’s media ecosystem—a process that culminated first with the long creative direction of John Galliano, then with the appointment of Glenn Martens, and, in recent weeks, with the announcement that the brand has found its first celebrity ambassador in Miley Cyrus. This has sparked discussion about what the philosophy of a brand like Maison Margiela should be. But where does this philosophy come from?

Why Did Martin Margiela Always Want to Remain Anonymous?

Martin Margiela, born in 1957 in Belgium, founded Maison Martin Margiela in 1988 alongside Jenny Meirens. From the outset, Margiela chose anonymity as a form of rebellion against the fashion industry, which in the 1980s and 1990s was dominated by the cult of personality surrounding designers, top models, and excessive commercialization. He never gave face-to-face interviews, refused photos, and often communicated via fax—somewhat like the Olsen twins at The Row do today, drawing inspiration from him in both design and approach. He didn’t even appear for the final bows at his shows, preferring to let the “collective” of the maison speak instead of himself. In a famous 2001 Vogue shoot, the entire atelier sat for a group photo where a single chair was left empty in the front row: that of the founder. His was an attempt to eclipse himself behind pure design, which was meant to transcend the illusions of celebrity and leave room for the clothes alone. When the MM6 line was introduced in 1997, it too remained programmatically anonymous and still is today.

A Portrait of Martin Margiela by Annie Leibovitz for Vogue US, 2001 pic.twitter.com/R0zOVOik7Z

— mars (@antifashun) July 19, 2018

Speaking anonymously to Interview Magazine in 2008, the brand’s collective explained: “What some consider a marketing strategy or a kind of snobbery is more like a sacrifice: he could have had all eyes on him, the glory, and the fame. Instead, he chose to step back, to let the clothes and the Maison speak for him, for his love of what he does, and for the respect he has for his team. […] We prefer that people react to a piece based on their taste and personal style, not on the impression they have of the individual or group that created it, as translated and publicized by the press.” Even after leaving the maison in 2009, Margiela remained invisible for years, though he continued to work as an artist.

How Was Anonymity Expressed in Martin Margiela’s Design?

@margielarchive Café de la Gare, a well-known theater and artistic venue in #Paris, was chosen as the location for Margiela's SS89 runway presentation. #margiela #maisonmargiela #martinmargiela #fashion original sound - margielarchive

The first and most significant code of the brand is the masks. They first appeared in the SS89 show at Café de la Gare in Paris, where models wore veils or masks to obscure their faces. Initially, there was a practical reason: the limited budget didn’t allow for hiring famous models like those at Dior, so the masks served to focus attention on the clothes, not the faces. But soon, the masks became a philosophical choice, evolving over time: in SS93, they were ethereal cotton muslin veils; in FW95, they were colorful; in SS95, they were black bands like duct tape censoring the eyes; in SS96, entirely black; in FW2000, they featured exaggerated fringes; and in SS2009 (Margiela’s last), they were combined with wigs and fake red lips.

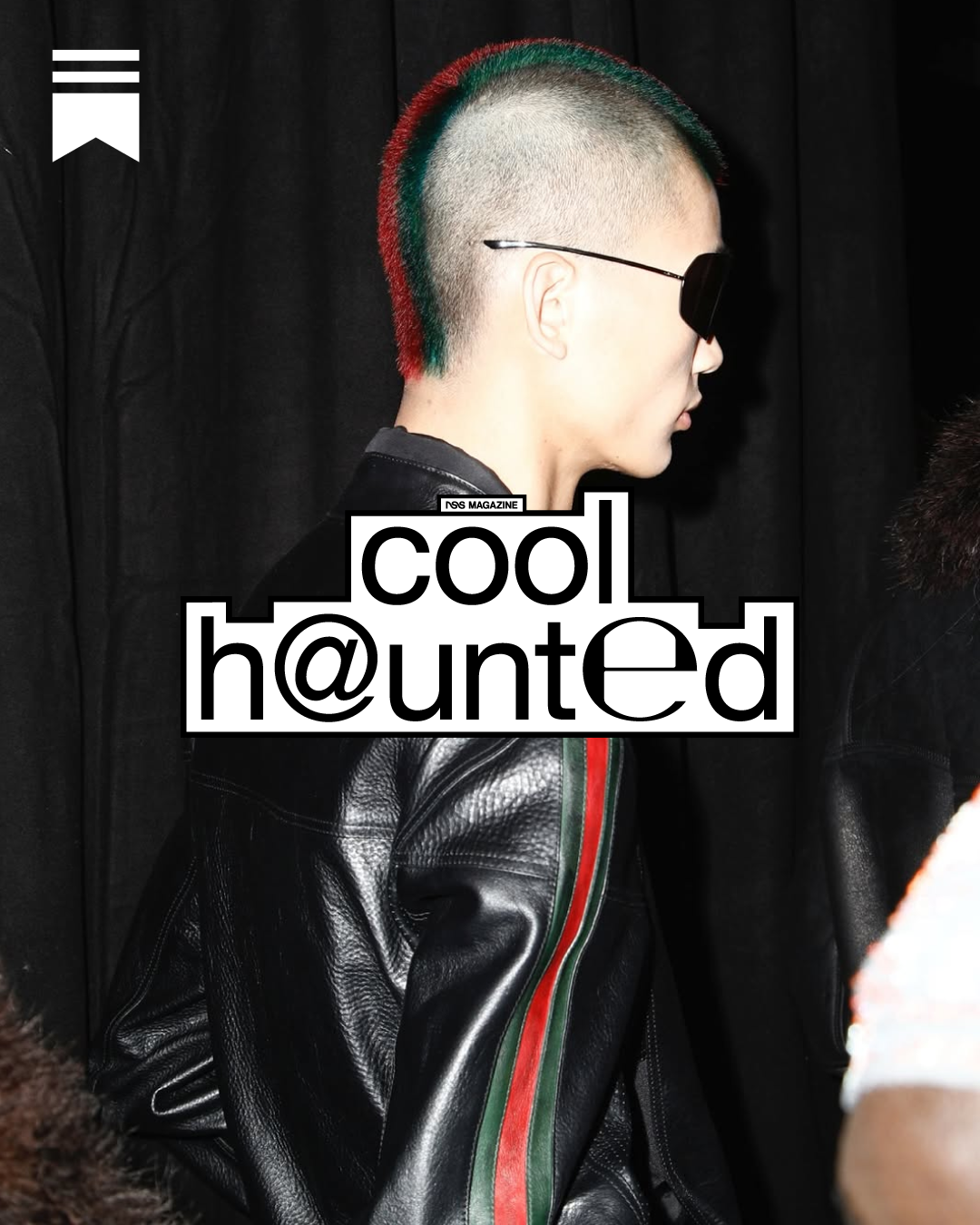

This tradition continues with his successors. Matthieu Blazy (head of the team from 2012) covered them in crystals, making them a hit with Kanye West, who popularized them during his 2013 Yeezus tour, and then with John Galliano. Glenn Martens, the current creative director, used them in his debut show in various forms: as veils, crystals, and, most notably, crafted from hammered and bent tin boxes shaped around the models’ heads like helmets. But anonymity extends to generic design and branding. All employees wear white lab coats to eliminate hierarchies and focus on the collective. Labels are blank and white for Artisanal products, without logos or monograms, rejecting obsessive visibility. Products are numbered from 0 to 23, with black circles indicating the line, while the “Replica” line reconstructs historical and vintage pieces—also “anonymous” because they lack a defined author.

The Meaning of White for Margiela

Another symbol of Martin Margiela’s desire to create a uniform identity and let time leave its marks is the use of white, called “bianchetto,” both on the clothing itself, such as the Tabi boots covered in white paint that chips and fades over time, creating unique colorations, and in the brand’s historic headquarters, the former Ecole Professionnelle de Dessin Industriel in Paris, acquired in 2004 in a state of complete disrepair. “There are two reasons we chose white: a practical one and a conceptual one,” a brand spokesperson told Another Magazine in 2009. “When Jenny [Meirens, co-founder of the brand] and Martin started, they collected furniture from all over. They had no money, and the furnishings were all in different styles, so to give a sense of coherence, they decided to paint them all white.”

White defined the brand’s identity during the iconic 2006 menswear show at the Teatro Puccini in Florence, when models arrived in luxury cars and white scooters, wearing re-editions of archival pieces, recreated entirely in white: denim patchwork, buckled jackets, shearling coats, ivory blazers, and heavy knitwear. All walked with their eyes covered by silver tape, foreshadowing the iconic L’Incognito glasses of 2008. The choice of white went beyond the clothes: the entire setting, from the theater to the surrounding spaces, was redesigned in the Maison’s image with newsstands, shops, ice cream parlors, posters, and even a large white hot air balloon suspended above the venue. Interestingly, this show demonstrates that, despite his love for anonymity, Margiela was even more passionate about theatricality and irony.

The “Replica” Line and the German Army Trainers

German Army Trainers were a shoe developed by Adidas/Puma (no clear answer which one) during the ‘80s for German Soldiers and Margiela liked the silhouette a lot so he made his own version of it. here’s some ones from the ‘80s for reference pic.twitter.com/Ql2PoEMeTt

— ean (@SlattSoldier) May 16, 2023

The Replica line was born with the FW95 collection, one of the brand’s most conceptual and revolutionary, where the designer experimented with the idea of faithfully reproducing existing archival and vintage garments, accompanied by a white label detailing their origin. One of the most legendary groups in the collection was “Clothing reproduced from a doll’s wardrobe,” where clothes from a 1960s doll, believed by many to be Barbie’s, were enlarged 5.2 times, retaining the original disproportionate buttons and stitching. In this gesture, Margiela not only introduced the notion of replica but deconstructed the idea of perfect sizing and ideal bodies, paving the way for a new conception of fashion as a critical language.

@rabbithole.arch This shirt/jacket and the whole collection perfectly describes the design language of the house and was extremely important for the whole fashion history. In 1994 Margiela launched the Replica line witch focused on reproducing identically already existing garments. And the first approach to it was reproducing dolls garments and resizing them to human size, with the same cut and disproportions Impossible to get it anywhere else, there hasn't been any other sold online, the only photos where you can see it are from the original 1994 photos from Martin's studio and from the museums. Available for $4200 on my Vestiaire and Vinted. #fashion #archivefashion #margiela #maisonmargiela #archive Angel - Massive Attack

The Replica approach, therefore, was not merely a recovery of used clothing (a practice that earned Margiela the label of “sophisticated grunge”) but a deliberate act of reconstruction and recontextualization. Military, athletic, artisanal, or vintage pieces were studied in detail, from proportions to materials, and reproduced to give new life to items already bearing witness to other eras. The Replica philosophy also emphasized the centrality of the process over the finished product: the most iconic piece is the GAT sneakers, now known as Replica, introduced in 1999, which replicate the athletic shoes of the German army originally designed by Adolph and Rudolph Dassler. In 2002, the brand purchased a batch of these sneakers, changed the labels, hand-painted the soles, and had each team member draw or write something on them, then sold them with a note inviting the buyer to add their own graffiti. In subsequent years, the shoes were reproduced, but those from 2002 remain the most coveted by collectors. When the brand expanded further in 2012, earning Haute Couture certification, it extended the Replica concept to perfumes with the eponymous line—now one of its best-sellers.