My idea of fashion, by Vittorio Lingiardi Thoughts on contemporary fashion

A few days before the release of his new book - Farsi Male, Einaudi - this Thursday’s newsletter features the signature of Vittorio Lingiardi, Italian essayist, psychiatrist and psychoanalyst, professor of Dynamic Psychology at the Faculty of Medicine and Psychology of the University of Rome “La Sapienza.” Lingiardi draws on the words of Roland Barthes and compares them to the present day to reflect on the meaning of the word “fashion”. We are now far removed from the 1960s, when the French critic was writing, and yet his theories still find fertile ground. Perhaps because, while fashions pass, return, and reinvent themselves, human vanity remains unchanged.

Lingiardi discusses fashion as identity, not clothing. As a tool for understanding what place we occupy in the world and communicating it to others, not for covering ourselves on cold days or countering heat on summer ones. Whether it’s keeping a beard long, groomed or scruffy, not ironing shirts, or wearing jeans with an undone hem, ultimately every stylistic choice we adopt suggests our cultural position, sometimes even our political leanings.

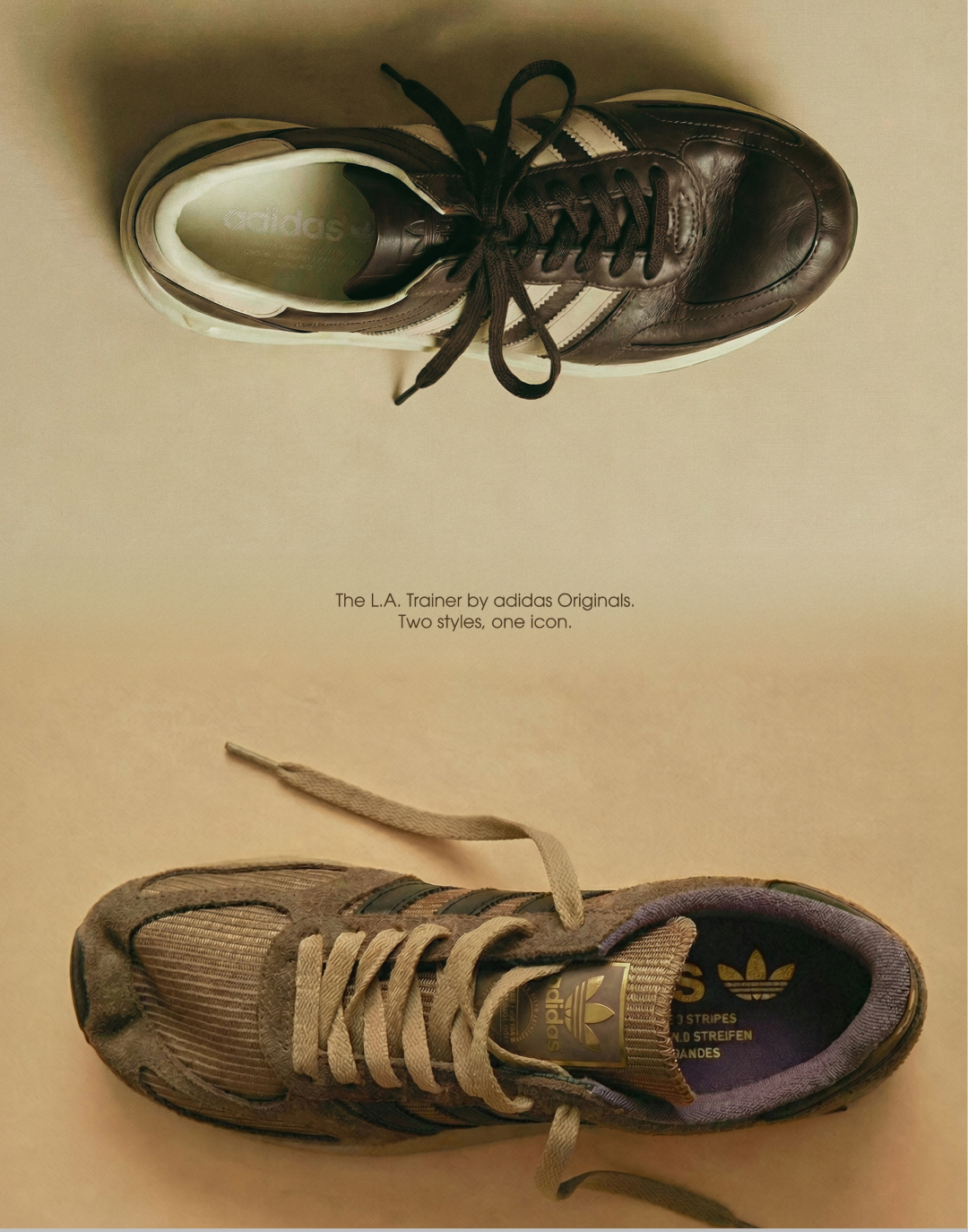

At a time when politics plays a central role in the fashion industry - both regarding market laws (just think of the tariffs Trump waves over the heads of brands around the world) and stylistic ones (recalling the boom of conservatism on the runway and in street style, quarter zips worn by rappers), fashion is ideology. Why do we dress today? According to Lingiardi, it’s a matter of aesthetics, whether they originate from the bottom up or from the top down, and also a matter of the body, which we rewrite through clothing, sometimes in unnatural ways. How much does the body define the garment, and vice versa? The final word is yours.

What do I write about fashion, I who know little about fashion? As I hum this little tune to myself, a personal deity comes to my aid, Roland Barthes, with his System of Fashion (1967). A personal deity, for example, because he writes: «I am a Daruma doll, which is constantly tapped, but which always regains its balance, supported by an inner keel (but what is my keel? the force of love?)». Returning to the System of Fashion, it is a study of sentences taken from fashion magazines (such as “blue is in fashion this year”), a journey through clothing codes. A work, Barthes says, that «concerns neither the garment nor the language but, in some way, the ‘translation’ of one into the other, insofar as the former is already a system of signs».

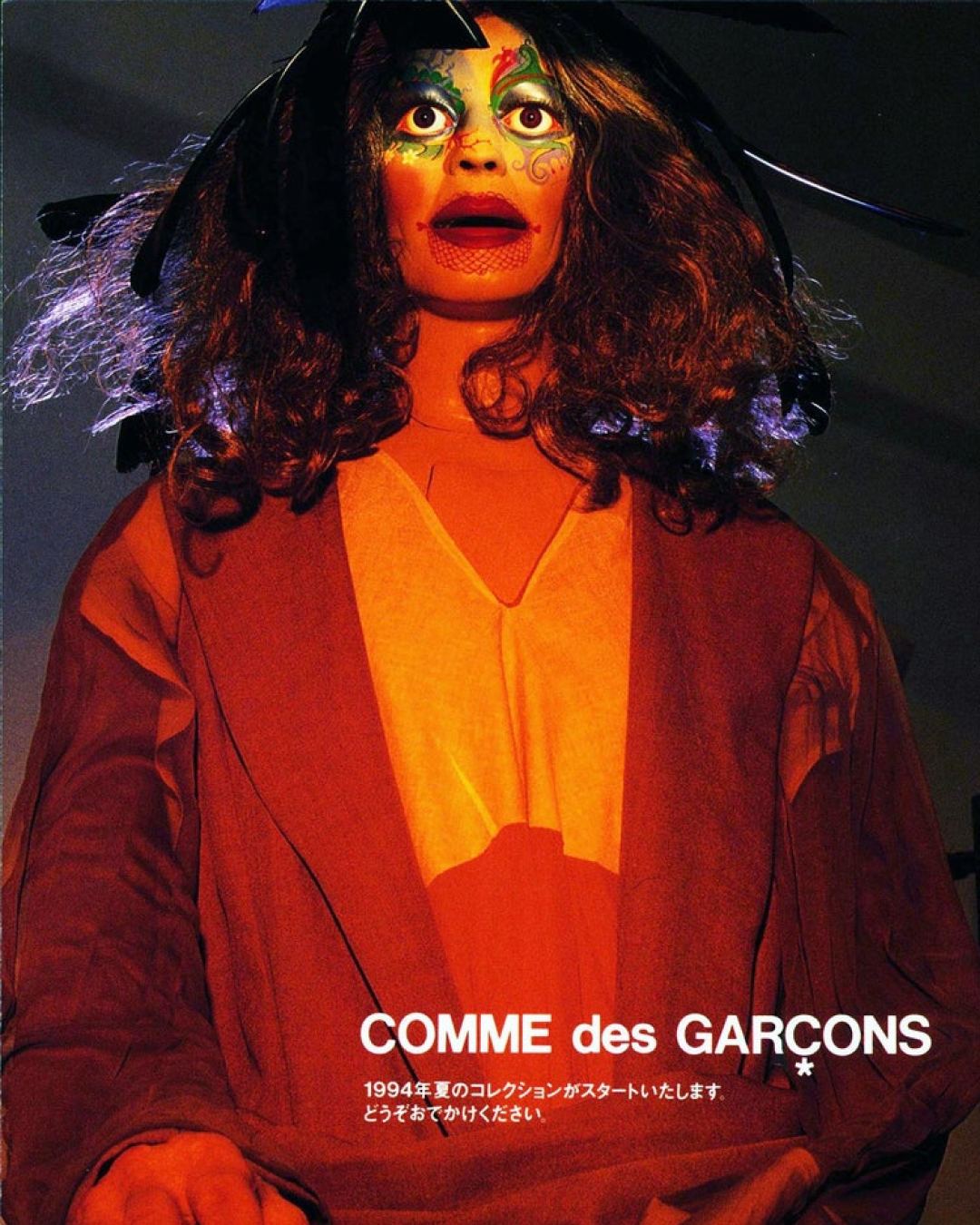

Fashion is therefore not an aesthetic fact, but a structured system of signs that produces meanings: a language. Barthes does not study real clothes, but written fashion, where the garment becomes narrative, symbol, ideology (another example: “She loves studying and surprise parties, Pascal, Mozart and cool jazz. She wears low heels, collects small scarves, adores her older brother’s sturdy sweaters and puffed, rustling skirts”). The real object disappears, and only its description remains; the fabric becomes material for discourse. Fashion is not “how we should dress,” but “how we should be”: a device that regulates identities, desires, social roles. Starting from the idea that fashion is above all the way the garment is “told” rather than “worn,” Barthes ends up stating that fashion needs the body yet at the same time erases it. The “real,” physical body - with its measurements, imperfections, postures - disappears and is replaced by an abstract body, a sort of linguistic mannequin that serves as a neutral support for the meanings of clothes. Fashion never describes the body, but what the body must do to highlight the garment: hide, stretch, adhere, discipline itself. In this sense, fashion does not represent the body, it normalizes it; it does not express it, it writes over it; it does not listen to it, it trains it. In Barthes’s discourse, the body becomes an effect of fashion: not a natural given but a cultural construct, idealized and shaped. «Fashion», he writes in a brilliant summary, «consists in imitating what, at first, presents itself as inimitable».

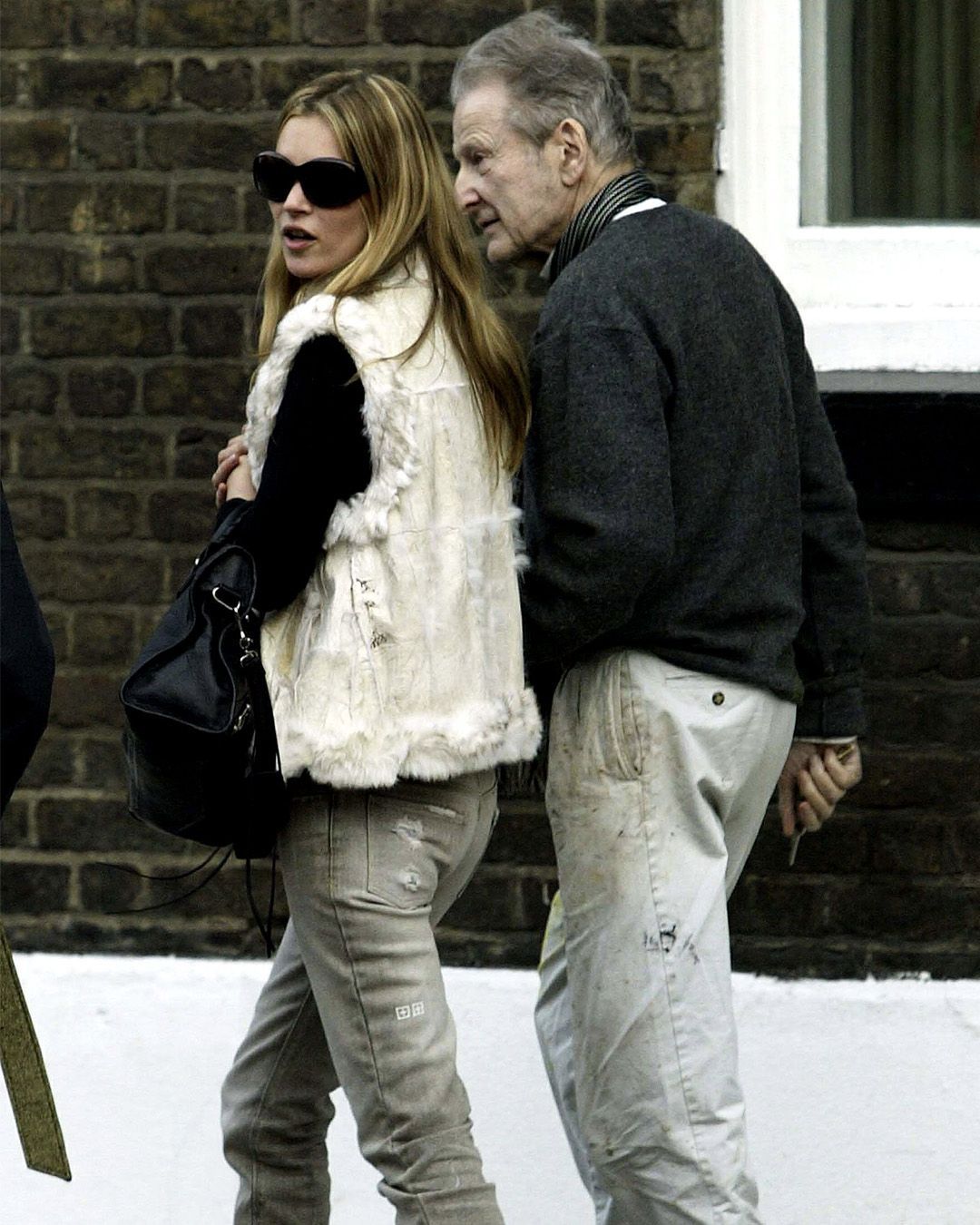

Since I know little about fashion, I don’t know whether Barthes’ observations from 1967 are still relevant. Whether fashion, by changing, has changed in its epistemological status. Over time, it seems to me that its inimitability has been enriched by the more or less prestigious ratification of aesthetic adventures born from below. Among the many interpretive layers suggested by Barthes, the one that interests me most is the relationship between clothing and the body of the person wearing it. Perhaps for me the “fashion system” works in reverse. What I look at is how much the body manages to triumph over fashion, how much the body defines the garment. I don’t care whether it is expensive or cheap, elegant or not, traditional or unexpected: what interests me is how the garment enters into dialogue with the wearer’s physical and cultural personality. This personality is made up of aesthetic or erotic markers that speak differently to each of us: almond-shaped eyes, high cheekbones, large hands, gapped smiles, small breasts, protruding ears, long legs, crooked legs, short legs. It is «the immense vocabulary of faces and profiles», Barthes says again, «in which each body (each word) signifies only itself and yet refers to a class». In this way we can experience both «the pleasure of an encounter» and «the illumination of a typology (the feline, the rustic, the one round as a red apple, the savage, the Laplander, the intellectual, the foolish, the lunar, the radiant, the thoughtful)». And be touched by an enchantment both sensual and cognitive: what seemed unclassifiable and inimitable finally finds its place.

So I have no exclusive preferences; I like baggy pants and button-down shirts, recycled materials and velvet jackets, midnight blue and forest green, but also pastel colors. It depends on how bodies wear them in their physical and cultural truth. Of course, I have my aesthetic standards and I remain perplexed by certain fashions (more those of the body than of the garment): overly decorated nails, for example, overly groomed beards, or excessively repetitive tattoos. Practices I observe as counterpoints to my idea of a living body, not plasticized, unique in its dialogue with the context and with the “fashion system.” I hope for a body that can live by reinventing, transforming, and overturning what is indicated to it as fashion. A body that - with its vitality, its way of inhabiting the world, its local, geographical, political, sexual cultures - gives value or beauty or grace or power to the garment, and not the other way around.