The return of Hipsters It will never end

The first things that come to mind when we think of the word hipster are handlebar mustaches, long beards, and oversized glasses frames. But also Wes Anderson movies, striped shirts, skinny jeans, MacBooks, and fixed-gear bikes. At least as far as aesthetics and status symbols are concerned. When it comes to music, the mind naturally jumps to Pitchfork, Vice, and the whole gang of indie-rock bands with improbable names, like Clap Your Hands Say Yeah, Death Cab For Cutie, and Vampire Weekend. In short, a summary of everything that was considered “cool” in an “alternative” way between 2001 and 2011. A world that seemingly disappeared at least a decade ago, but maybe never really left and now seems ready for a comeback. After all, following the return of the Oasis and the ‘90s, it was inevitable to move on to the next decade.

Death and Rebirth of the Modern Hipster

@isaach.p Average Hipster conversation #isaachp #trending #fyp original sound - Isaac H.P

The decline of the modern hipster occurred when the mainstream side began to overpower the underground one, swallowing the very concept of the hipster caught between both worlds. But another fundamental element that united all versions of the hipster—from the Black hipsters of the 1940s to modern ones—was their (real or not, it doesn’t matter) ability to be essentially seen as synonymous with superior cultural knowledge compared to the masses. Generally, hipsters are known for claiming they discovered a new cultural trend first, hence the (self-)ironic T-shirts saying: “I Listen To Bands That Don't Even Exist Yet”. It’s understandable how this kind of prolonged behavior became somewhat annoying and a source of irony, eventually turning into self-parody: for example, the TV series Portlandia (sadly never aired in Italy) with Carrie Brownstein from Sleater-Kinney and Fred Armisen, brilliantly mocking all hipster stereotypes. Or the famous joke from The Onion: “Two hipsters angrily call each other hipster.”

Coming to the present: is it true—as rumored—that hipsters, who fell from grace in the 2010s, are coming back? Well, there’s definitely a certain favorable atmosphere. As mentioned, the world has changed rapidly in recent years, and the search for authenticity in art is surely a topic back in the spotlight, given recent technological developments and new ethical implications related to creative content generated by artificial intelligence. Alongside the question of the authenticity of the artistic object, there's also the issue of so-called artistic curation—the search and selection of the most worthy cultural objects in an age of infinite choices.

@lysslester i carried my nikon dslr everywhere with me lol #2010s #indiekid #hipster #2009 Deadbeat Summer - Neon Indian

In the age of social media, we witnessed the rise of influencers—book bloggers, music tellers, etc.—who can be seen as the capitalist degeneration of the hipster who once told you what “real music” was. Except, while the hipster did it for self-affirmation, building a sort of socio-cultural capital, influencers often promote cultural products for profit, usually in a clear and transparent way. The next step was the rise of the algorithm: today it rules and guides your cultural consumption, but unlike human curators, it’ll never suggest anything too different from what it already knows you like, making it unlikely to lead you to discover anything truly new. That’s why “curators/creatives”, once dismissed, now seem more necessary than ever and have slowly reorganized in new forms: think of the boom in podcasts and Substack newsletters. Another concrete expression of the new hipsterism is the site Perfectly Imperfect (also originally born on Substack), where basically a bunch of cool people recommend cool cultural products. The ABC of hipsterism.

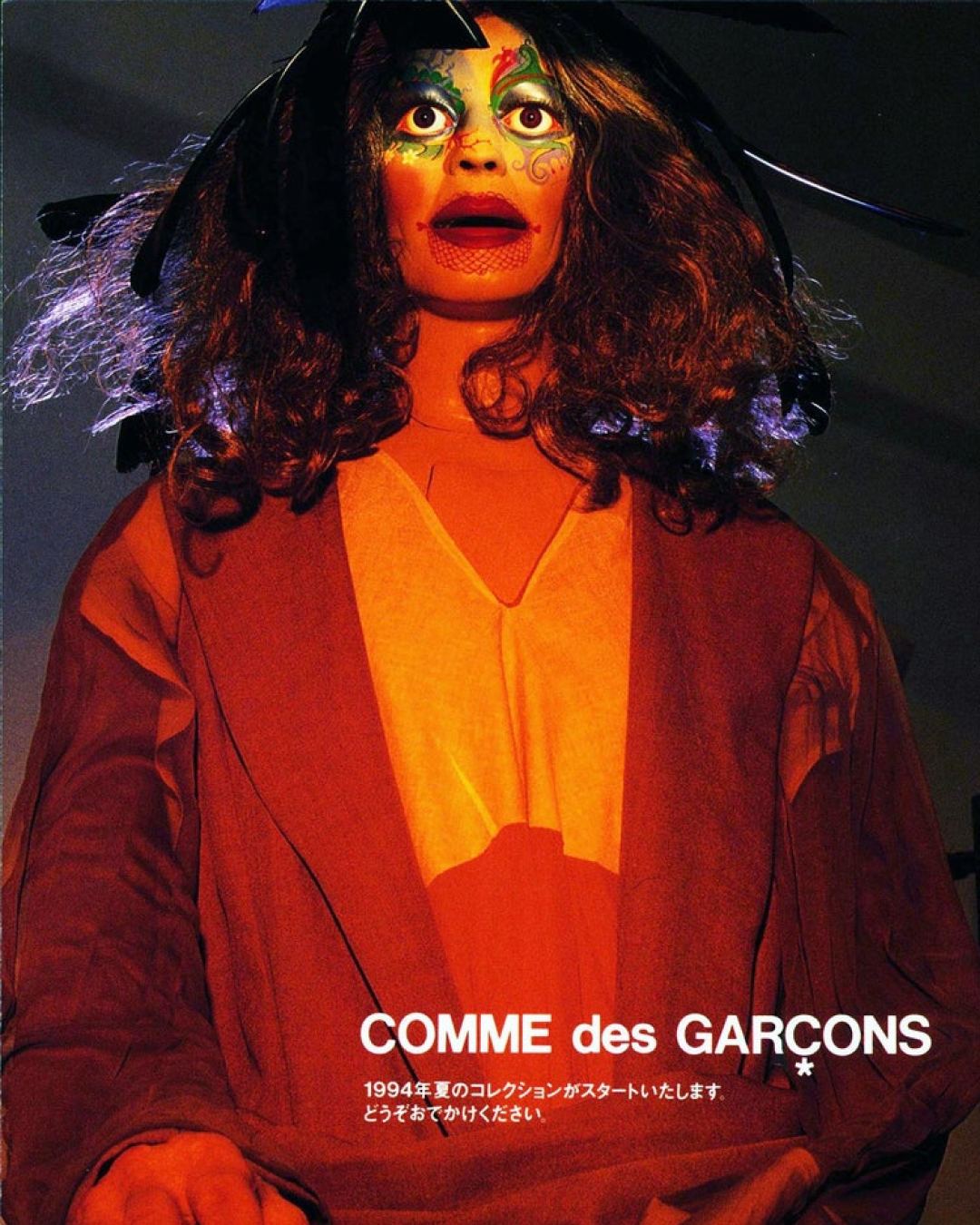

Although hipsterism is primarily a state of mind, it has always come with a clearly defined aesthetic, which is in fact the first thing we associate with hipsters. Well, by now you’ve probably noticed that for some years people have been talking insistently—we’ve talked about it too—about the return of the indie sleaze style, a neologism coined by TikToker Mandy Lee to describe the deliberately scruffy style of the early 2000s, which actually characterized super stylish bands like New York’s The Strokes or their British counterpart The Libertines.

@pietrofantini__ non avrò bisogno delle medicine degli psicofarmaci del lexotan #lexotan #icani #niccolocontessa #postmortem original sound - Pietro Fantini

Now, both the Strokes and the Libertines have tried to make a comeback in recent years without much success. But this year, things seem different, and lately there’s been a lot of buzz about two big comebacks from “indie-hipster” bands (pardon the redundancy). One is the reunion of The XX, headlining both Coachella and Primavera Sound, and just recently invited to the Prada show at Milan Fashion Week. The other is Tame Impala, Kevin Parker’s fake “band” that never really stopped, just slowed down, now returning with a pair of recent singles—End Of Summer and Dracula—that bode well for their upcoming album (out October 17) and the 2026 tour, which includes a stop in Italy. Narrowing the focus to the Italian scene—what could be more hipster than the return of I Cani? They reappeared out of nowhere with a surprise album and a tour that sold out unexpectedly, forcing organizers to add more dates. Clearly, hipsters are coming back—or maybe they never left. And if we look at their history, it’s likely that the return of the hipsters—as a song by I Cani says - «It will never end»

History and Evolution of the Term Hipster

To better understand the phenomenon, it’s worth knowing that, in reality, even the hipsters of the 2000s were already "returning hipsters": in essence, it’s as if the very concept of the hipster is destined to be born, die, and then return and evolve over time. The “originals,” in fact, date back as far as the 1940s and had apparently little or nothing to do with the ones we just described. The term hipster originally emerged within the African American community as a synonym for hepcat, referring to jazz enthusiasts, especially those who were less traditional, more avant-garde, and closer to the emerging bebop scene.

As early as 1948, journalist Anatole Broyard described them unflatteringly in his essay A Portrait of the Hipster, published in Partisan Review, effectively declaring the movement’s demise. In Broyard’s words: “The hipster promptly became, in his own eyes, a poet, a seer, a hero”, and the hipster lifestyle “became more rigid than the institutions it had decided to defy. It became a dull routine. The hipster, once an irreducible individualist, underground poet, guerrilla, had become a pretentious poet laureate.”

@tim.collins he served me an overpriced burger... #hipster #hipsterphase #indiekids #2010snostalgia #2010sfashion #2010sthrowback #manbun #comedyskit #parody #millennialsoftiktok original sound - tim collins

In the 1950s, the term evolved to describe a figure of white counterculture who, in some way, admired the vitality of African American jazz musicians and their bohemian lifestyle, free from social conventions. Writer Norman Mailer explored the concept in his famous essay titled The White Negro: Superficial Reflections on the Hipster, published in Dissent in 1957. According to Mailer, the white hipster was an existentialist whose only viable response to modern reality was to “live with death as an immediate danger, divorce from society, exist without roots, and undertake that unexplored journey toward the rebellious imperatives of the self.” Jazz remained essential, Mailer wrote:

“To give voice to the character and quality of his existence, to his rage and to the infinite variations of joy, lust, languor, growl, cramps, pinches, screams, and despair of his orgasm. Because jazz is orgasm; it is the music of orgasm, and so it spoke to the entire nation, it had the communication of art even where it was watered down, perverted, corrupted, and nearly killed. It spoke in whatever popular and sanitized form of the instantaneous existential states to which some whites could respond—it was truly a communication through art because it said: I feel this, and now so do you.”

The hipsters persisted throughout the 1960s (the hippie movement actually branched off from them) before fading into obscurity in the ’70s, only to be reborn in disguise in the late ’90s, eventually reaching their peak between 2003 and 2010. Like every respectable subculture, as soon as the hipster began to spread more widely among the general public, it also began to be viewed negatively and described in derogatory terms.

Even though there were many legitimate artists among them, Simon Reynolds—today considered arguably the most important living music critic—described them as a class of curators/creatives who, “work in fields like Information Technology, media, fashion, design, art, music, and other aesthetic industries. A class of quasi-creatives—pejoratively known as hipsters—found in any city in the developed world large and wealthy enough to support an upper middle class worthy of the name.”

@tinfoilbot5 let’s get far far away from this town #hipster #nostalgia #2010s #portland Song For Kelly Huckaby - Death Cab for Cutie

Canadian writer Douglas Haddow even went so far as to say that the spread of hipster style represented “the end of Western civilization,” due to its nostalgic inclination toward the past: vintage clothing, Polaroids, vinyl records, etc. But as Tiziano Bonini, author of a valuable modern essay on hipsters, wisely observed, this kind of obsession with the past was actually an obsession with the search for authenticity—in music, in design objects, in food, and so on. The hipster, Bonini wrote in 2014, “is the most significant cultural expression of the generation of the 2000s, because this generation grew up with a level of insecurity never experienced before by previous generations. Precarious in work, digitized in social relations, this generation needs—even just symbolically—to rediscover the authenticity of things.” If we think about how our society has evolved a decade later, with the proliferation of fake news and AI-generated content, we can understand just how much the issue of authenticity is today more than ever a fertile ground for yet another hipster revival.

The Question of Authenticity

@swag.on.the.beat Name one Harley Davidson song… #swag #fyp #hipster #davidguetta #xyzbca #foryou original sound - swag.on.the.beat

The issue of intrinsic authenticity in the modern hipster has been most clearly explained by what we can consider the most insightful and attentive scholar of the phenomenon to date: American literary critic Mark Greif, associate professor at the New School University in New York and co-founder, along with Keith Gessen, of the literary magazine «n+1». Among many things, Greif is also the author of two key essays on the topic: The Hipster in the Mirror and What Was the Hipster, both published in 2010 in the New York Times and New York Magazine, respectively.

In these essays, in addition to debunking the myth that there is no clear definition of hipster, Greif traces the social and cultural substratum that led to the birth of the modern hipster in the 2000s. The starting point was the late 1990s youth subculture, often called “alternative” or “indie,” which defined itself as anti-consumerist—the Seattle people, the No Logo generation, etc. But this sort of “neo-bohemia” made up mostly of young aspiring artists with precarious