There’s a new substance popping backstage at Fashion Week Model Theodora Quinlivan admitted to using drugs on the catwalk, yet no one was surprised

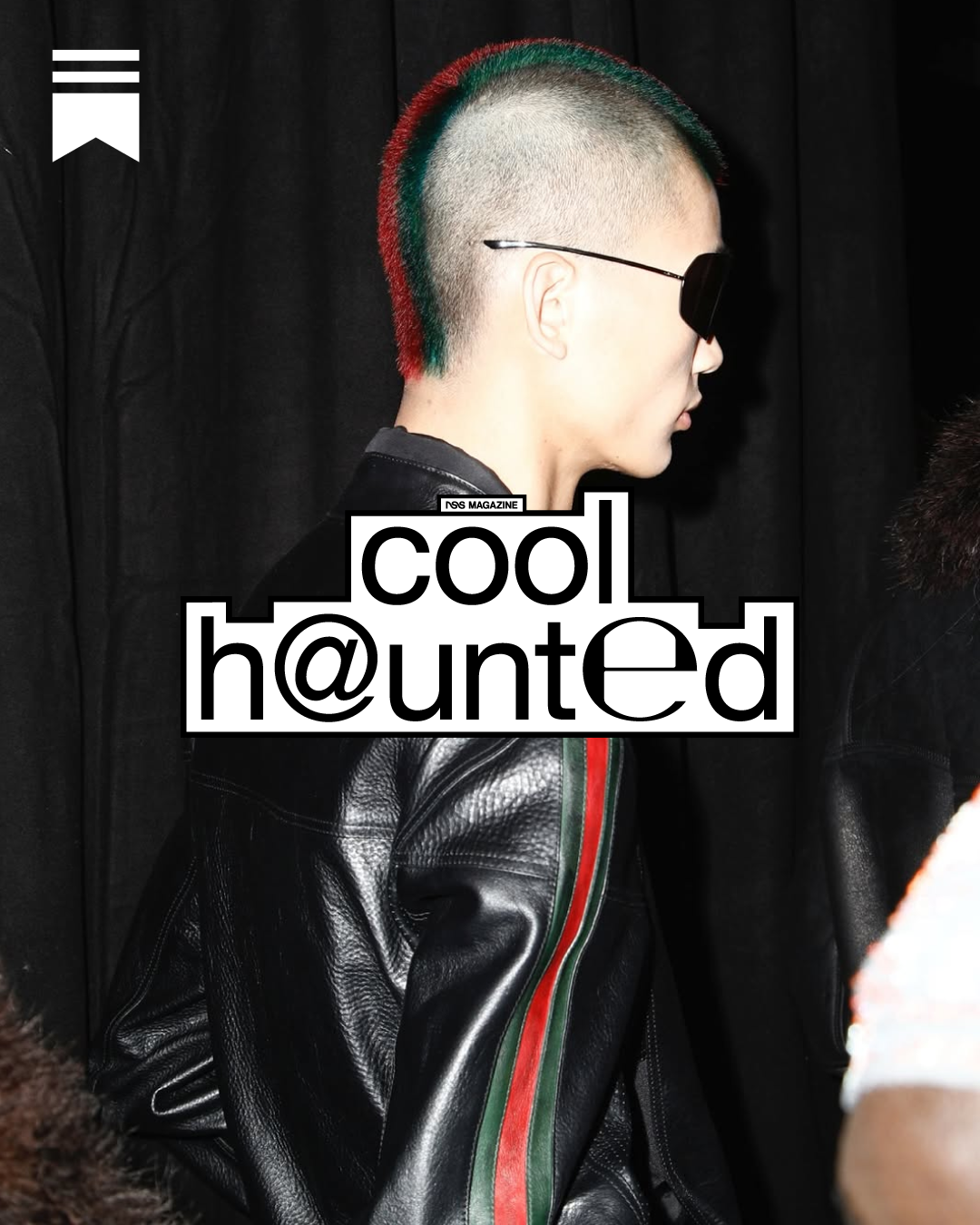

«I did poppers before walking Dsquared2… a couple times», says Theodora Quinlivan on TikTok, where she is known as @teddyquinlivan6. The images that follow show her strutting down the runway with a fixed gaze and loose, fluid movements. «And also backstage in a couple other shows, but Dsquared2 was the most important one», she adds nonchalantly. The first video in the series Diaries of a Difficult Model has already reached 136,000 views and collected positive comments ranging from «mind you this is my first impression of you, and I love it» to «no because thats very on brand they should pay u extra». A reaction that says a lot about how fashion today narrates a phenomenon that has never been foreign to it: openly, without shame, without consequences. Welcomed with admiration.

Are the days of Kate Moss really back?

@ksynote one sneeze and it’s snowing.#fyp #modeling #katemoss original sound - KEYNOTE.

Makeup and hair done, a quick hit of poppers and off you go. «I would let it rip. And I would serve cunt every single time», Quinlivan admits, which, in plain terms, means absolutely killing it with confidence and pride. In the TikTok video, the model recounts an initial concern about taking drugs at her workplace. A concern that quickly dissolved once she realized that backstage there were far heavier substances circulating. By comparison, poppers felt like child’s play.

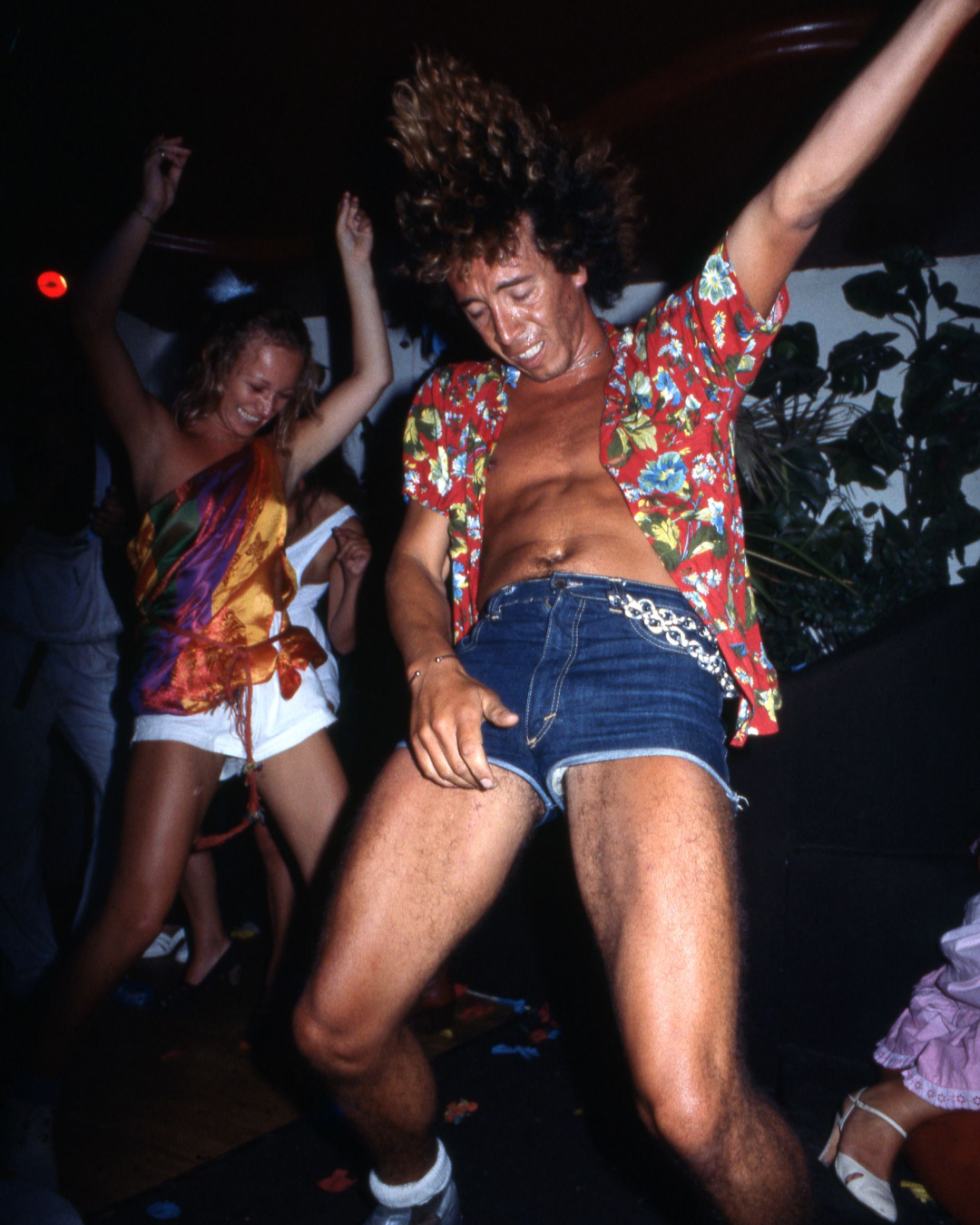

There is something ironic about starting the new year by talking about drugs in fashion. It feels like watching a script repeat itself. At the beginning of last year, Kate Moss – also known as Cocaine Kate and Kate Mess – went viral on TikTok not for her work as a supermodel, but for the imagery tied to her extreme lifestyle, marked by substance abuse and a turbulent love life. The audio track that sparked this renewed fame went: «She’s had plenty of drug problems and has dated some questionable men. She’s been blamed for promoting anorexia and heroin use, and her nicknames include cocaine kate & kate mess. She’s Kate Moss and she’s a rockstar trapped in a supermodel’s body».

Images of a high-as-a-kite Kate Moss were elevated to timeless icons; girls and models showcased their thinness and Y2K-inspired outfits. Years of wellness culture rhetoric wiped out by a few seconds of audio. At the same time, on Chinese social media, the “cocaine walk” was circulating: a sharp, jittery stride paired with wide-open eyes, one you might recognize on Mariacarla Boscono.

The fashion–drugs pairing

model cara delevingne dropped a coke baggie and tried to hide it with her shoe: pic.twitter.com/CrKo3OEMyk

— popculturediedin2009 (@pcd2009) May 18, 2023

From Theodora Quinlivan’s 2-minute-and-24-second monologue, two key aspects emerge. The first is the complete lack of hesitation in recounting what happened. No justification, no shame, no regret. In fact, the model explicitly states that her lack of professionalism is entirely irrelevant when weighed against an impeccable performance. She even hints at a certain indifference from Dsquared2 founders Dean and Dan Caten toward this shortcut. She talks about after-parties, fun, and extreme shows: the classic house menu.

The second aspect concerns the public reaction: comments do not condemn, they celebrate. Cheers, ovations, someone even asks for her zodiac sign in an attempt to get to know her better. It is a complete reversal compared to the scandal that hit Kate Moss in 2005, paparazzied by The Sun alongside four lines of cocaine on a table. Let’s be clear: the romanticization of drug use in fashion has always existed.

In the early 2000s, cocaine, amphetamines, and ecstasy were markers of belonging to an elite that lived at night, traveled constantly, and made excess an aesthetic code. It was embedded in images, shows, and campaigns. The images published by The Sun brought into the open what had until then remained in the shadows, marking the end of the era of media innocence. A shift that came at a high cost for the English model: Chanel, Burberry, and H&M canceled planned collaborations, resulting in a total loss of $4 million.

So what has really changed?

For a long time, the drugs–fashion duo rested on an unspoken principle: if the problem is individual, it does not concern the system. In 2011, John Galliano was arrested in Paris for antisemitic insults under the influence of alcohol and drugs and lost his creative directorship at Dior. A reaction that reveals an uncomfortable truth: fashion does not punish abuse, it punishes the loss of image control. The system protected him despite being aware of his addictions, as long as he generated symbolic and economic value, only to distance itself once he became a threat to LVMH’s reputation.

The same happened with Lee McQueen. After taking his own life at a very young age, following the use of cocaine, sleeping pills, and tranquilizers, media attention focused on the “tormented genius”, on clinical diagnoses (including insomnia, anxiety, and depression), rather than on the role of the industry. In 2015, The Sunday Times wrote: «Pereira (ed. Stephen Pereira, McQueen’s psychiatrist) identified the extreme ends of the fashion world as a problem to McQueen, as he plummeted from the giddy highs of the catwalk shows to the comedowns afterwards and the severe lows they took him to». McQueen suffered from the extremes of fashion, a well-known mechanism that has never truly been questioned.

Today, however, this framework seems to have collapsed. TikTok reactions show no scandal, no outrage, no solidarity. There is transparency turned into content, consumption turned into storytelling, and an audience that applauds. Comments stress the iconic nature of taking poppers before stepping onto the runway, underline personal involvement in the story, and emphasize amusement. If in the 2000s drugs were fashion’s dirty secret, today they are its viral content. And when excess becomes entertainment, there is no one left to shock.