The urban myth of Leoncavallo A few days after the eviction, we retrace the history of one of Italy's longest-running social centres

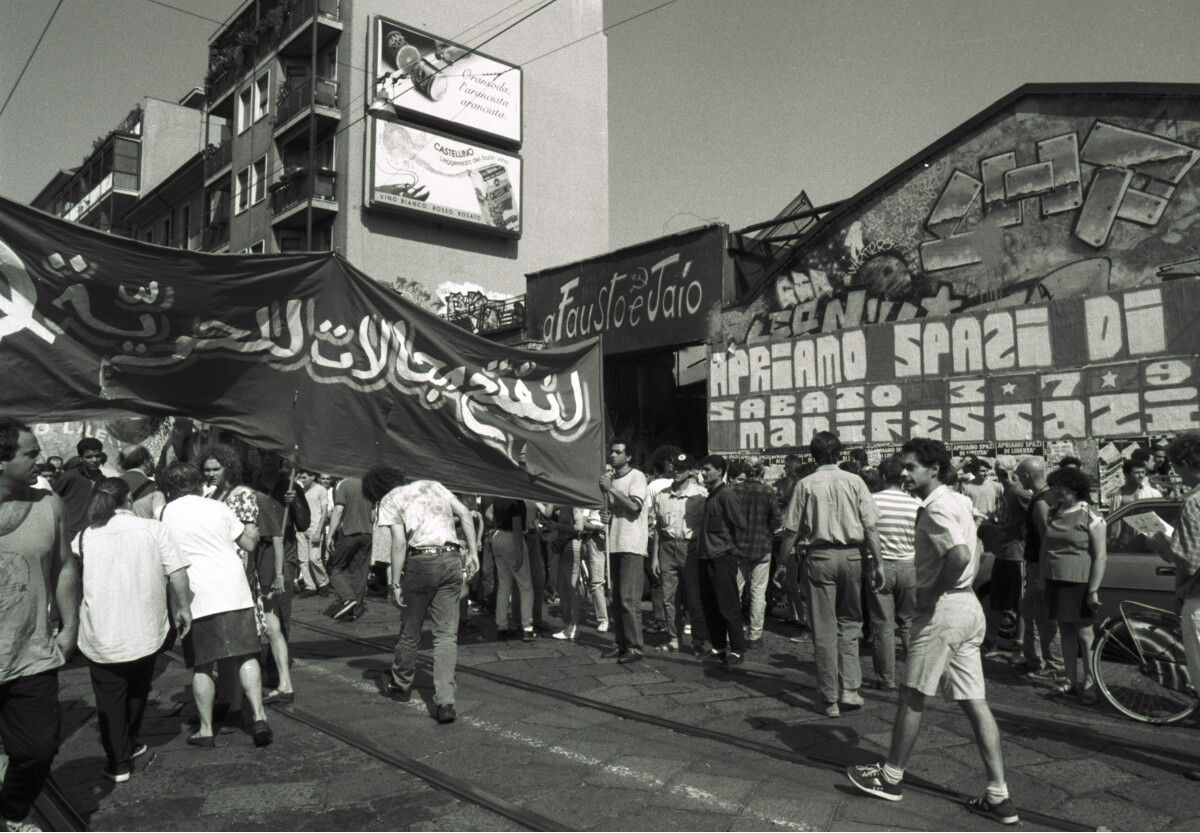

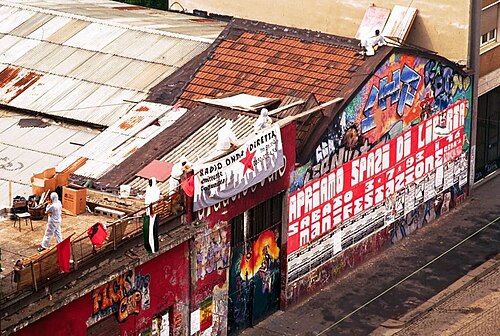

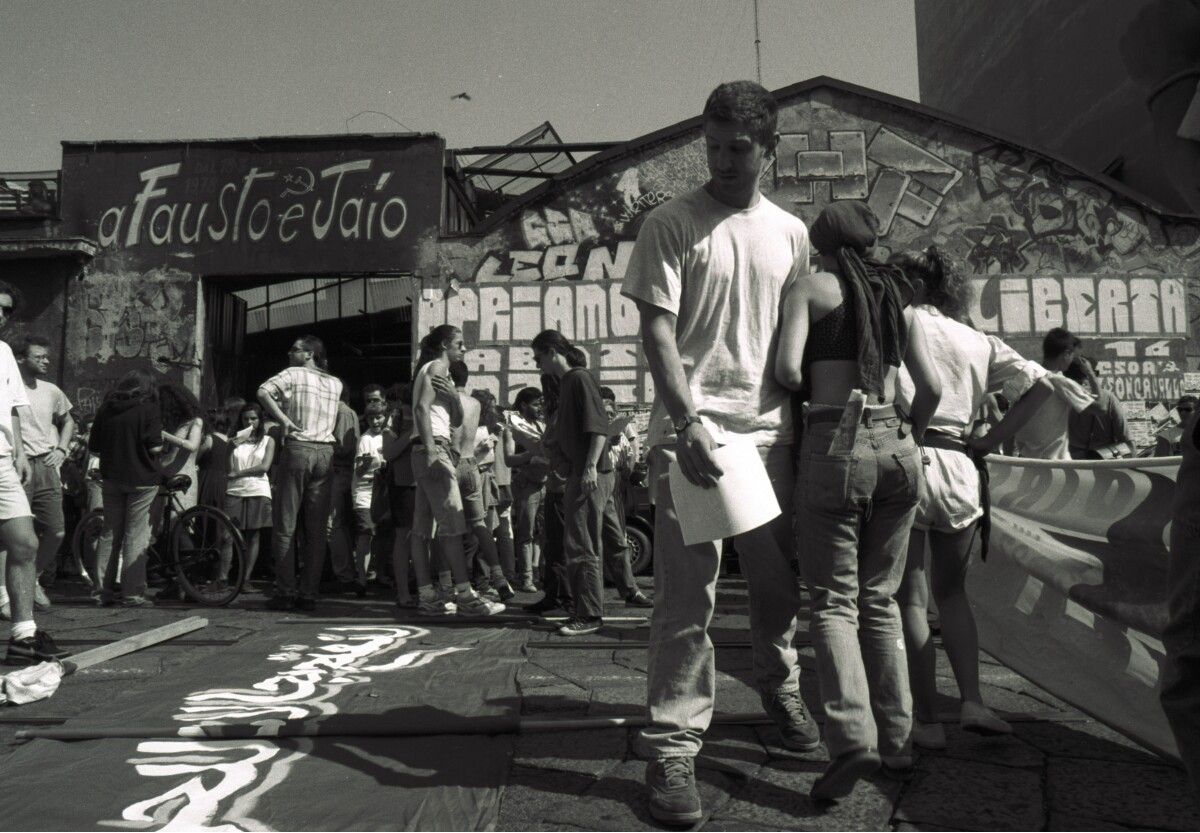

The Leoncavallo has never been just a social center. It was an idea of the city, a laboratory of culture and conflict that in Milan has resisted for fifty years, an urban epic marked by occupations, evictions, rebirths, and new forms of sociality. Born on October 18, 1975 in an abandoned pharmaceutical factory on Via Leoncavallo 22, in the heart of a working-class neighborhood, the center took its name from the street itself, quickly becoming a symbol of the extra-parliamentary left and of counterpower movements. In those complex years, amidst protests and clashes, Leoncavallo presented itself as a self-managed alternative to the lack of services in the urban outskirts: print shops, independent radios, popular schools for literacy, and spaces for theater, music, and feminist activism were born.

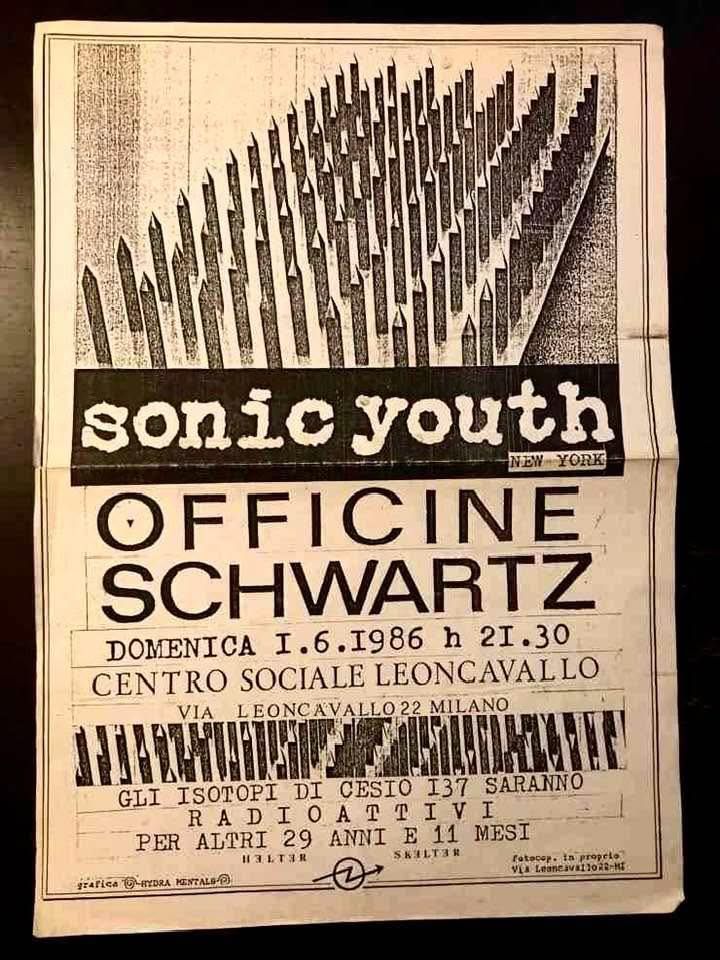

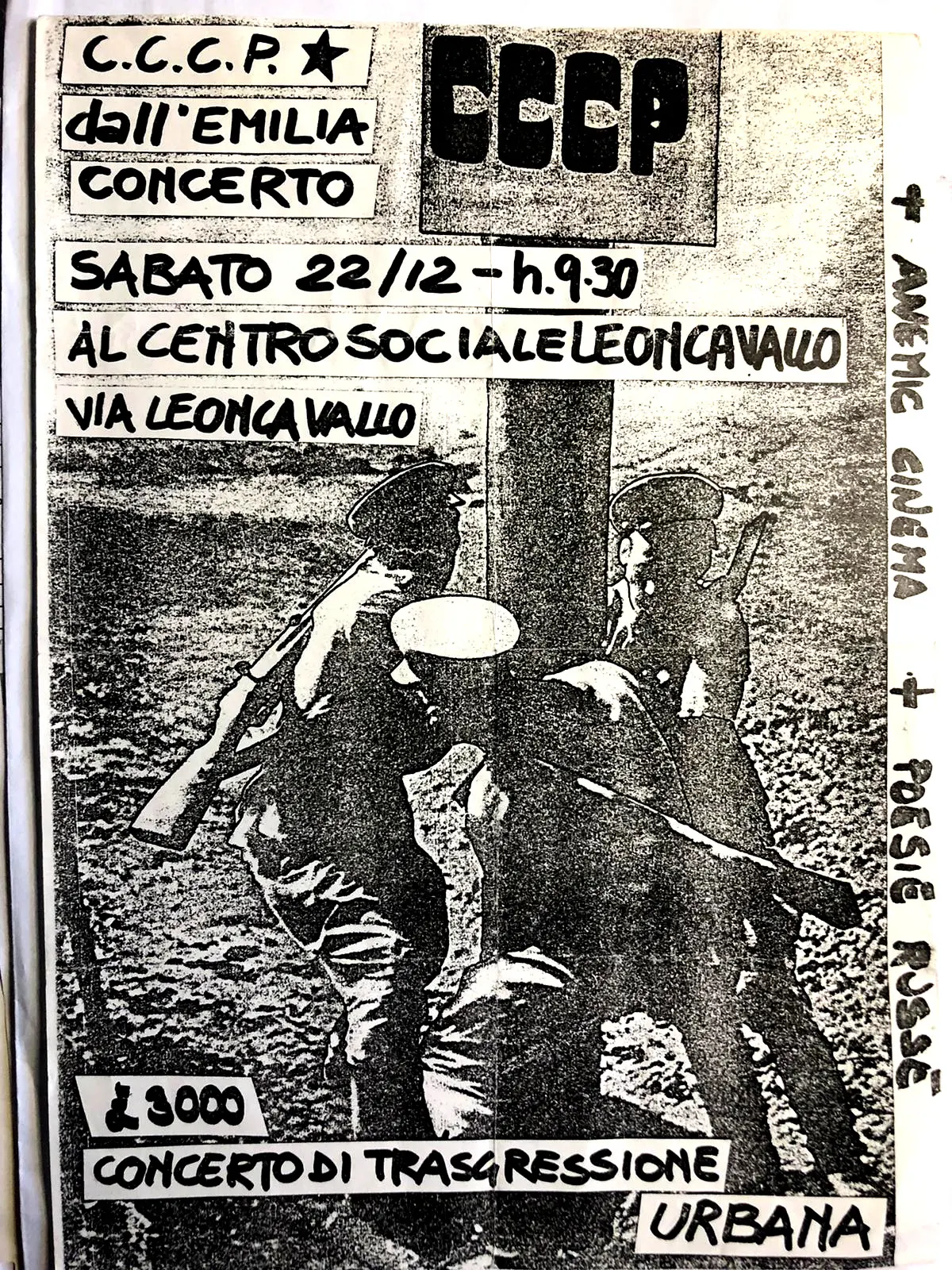

In the Seventies and Eighties, Leoncavallo was much more than an occupied place: it was a meeting point for students, workers, artists, and musicians. Its role as a hub was tragically confirmed in 1978, when Fausto and Iaio, two young regulars of the center, were killed in circumstances never clarified. Their death made Leoncavallo a symbol of a generation struck by the political violence of the Years of Lead. In the following years, its walls hosted layers of heterogeneous cultural experiences: from rebellious punk to anti-nuclear and student movements. Its halls became catalysts for independent music, hosting international legends such as Fugazi, Sonic Youth, and Public Enemy, alongside theater performances, exhibitions, and creative workshops.

Legal and real estate disputes have marked much of its history. After years of lawsuits, evictions, and partial demolitions, in 1989 the historic area was purchased by the Cabassi family, well-known Milanese real estate developers, who began a long legal battle with the collective. This tug of war culminated in 1994, under the administration of Marco Formentini, with the final eviction of the historic site. After a transitional period in Via Salomone, the collective occupied the former paper mill at Via Watteau 7, in the Greco district, where Leoncavallo found its longest-lasting and most structured home, resisting for over thirty years.

In the Via Watteau location, the center experienced its most prolific season. There, workshops for screen printing, bicycle repair, theater spaces, the popular Italian school for migrants, and a dense calendar of concerts ranging from techno to reggae, from jazz to dub parties that drew thousands of young people were born. The center also hosted the urban regeneration project DaunTaun, the underground space that in 2003 became the first public street art event in Italy, today protected by the Superintendency of Cultural Heritage as a testimony of an urban art that marked an era. Every year, events such as the Sowing Festival and the Harvest Festival set the rhythm of the center, transforming it from a place of conflict into a non-recognized common good.

Leoncavallo has been the stage of as many as 133 eviction attempts, as reported in various journalistic investigations, and at the same time of endless political negotiations. Its fate has always remained suspended between legalization and removal, between its role as a place of popular gathering and the hostility of those who considered it an anomaly. When in 2021 Macao, another major Milanese social center, closed, Leoncavallo remained the last stronghold of an urban tradition made of occupations and self-managed spaces. For many, it had become a cultural infrastructure that made up for the shortcomings of the official city, a refuge and a laboratory for young people excluded from the mainstream market.

To tell its story means retracing the profound transformations of Milan, from the working-class neighborhoods of the Seventies to the global metropolis of the 2000s. Leoncavallo embodied the other face of the city: inclusive, radical, conflictual, and often uncomfortable. Thousands of people passed through its halls not only to dance or listen to music, but to learn, to meet, and to live a different kind of sociality.

The fiftieth anniversary of Leoncavallo comes at a fragile moment, after yet another eviction in August 2025 from the Via Watteau site. The future of the center remains uncertain, between the possibility of a move south to the Corvetto district and that of a new political compromise. But beyond its physical location, Leoncavallo has already entered Italian urban and cultural history. It has become a symbol of resistance and reinvention, a witness to a city in transformation and to generations that never stopped seeking spaces to imagine alternatives. Perhaps Leoncavallo is not just a place: it is a collective story that continues to be rewritten, even after fifty years.