A Harvard linguist is studying TikTok slang ChatGPT said: It's called "algospeak" and includes terms like skibidi, sigma, and looks-maxxing

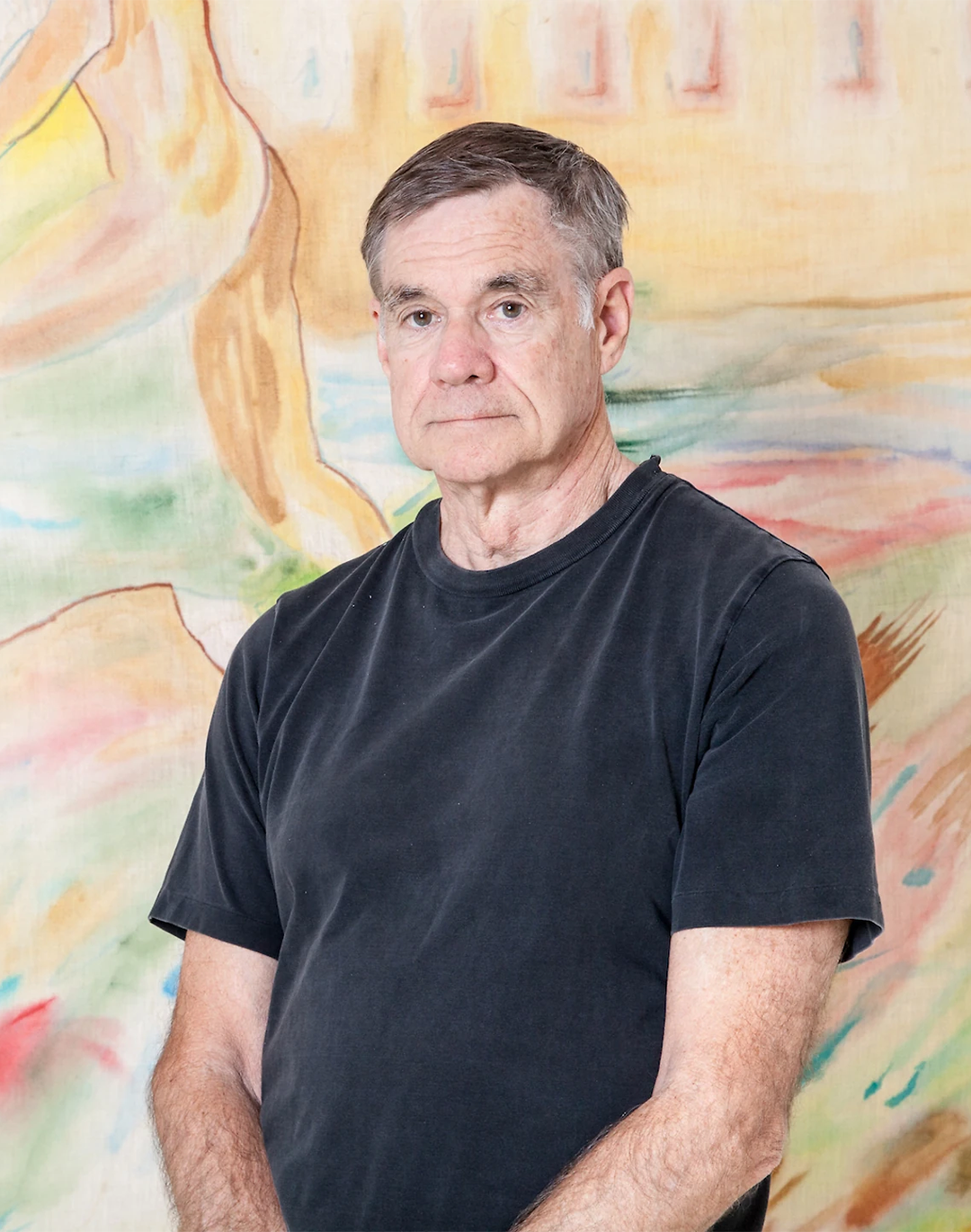

Every generation has had its own lingo. In the 2000s, in Italy, people used phrases like «come butta?», while in English-speaking countries gnarly was popular to describe something extreme. Idioms repeated to exhaustion, only to eventually fade into oblivion. With the rise of TikTok, it wasn't just fashion that began experiencing an incredibly fast turnover of trends, but also the slang and language used by young people. If in 2021 it was impossible not to use words like slay or seesh as fillers, with the arrival of Gen Alpha, online people started talking about brainrot, as the terms used by the new generations often appeared disconnected from a specific cultural matrix (such as, for example, AAVE, African-American Vernacular English). In addition to terms like skibidi, sigma, looks-maxxing, used as adjectives to describe a person, little by little, a parallel language to English emerged: algospeak. On social media, algospeak refers to the use of coded expressions to bypass automatic content moderation. It’s used to discuss topics deemed sensitive by moderation algorithms, avoiding sanctions such as shadow banning or demonetization: unalive means suicide, seggs means sex, lebanese is used for lesbian, corn (or sometimes even directly the emoji) shifted from meaning maize to referring to porn, and so on. However, the phenomenon has not remained confined to the web. In the United States, an increasing number of middle school students are adopting these substitute terms in their vocabulary. This is where the research of Adam Aleksic, better known as @etymologynerd on social media, a linguist from Harvard, comes into play.

@etymologynerd It's simultaneously so dystopian and so cool that a new way of writing has emerged to avoid AI censorship #linguistics #language #algospeak #etymology original sound - etymologynerd

Aleksic explained to the New York Times that the more he delved into the subject, the more he realized just how much algorithms influence every aspect of contemporary linguistic evolution. A mechanism that accelerates the spread of expressions born online, projecting them into mainstream culture in just a few days, but that at the same time strips terms from their original context faster than ever before. Aleksic says he started noticing this pattern specifically by observing TikTok and creator vocabulary, realizing that certain terms would go from niche videos to viral hashtags within a week, losing their original connotation in the process. According to Aleksic, algospeak is no longer just about bypassing explicit words on social media: it’s a true linguistic ecosystem, where words rocket from the margins to the center of public conversation in an instant, only to fade just as quickly. When influencers change their way of speaking to maximize visibility, that register is immediately absorbed and replicated by their audience. Yet, as he emphasizes in his book, this phenomenon is not necessarily a bad thing: «Moments of linguistic upheaval, like the spread of netspeak in the early 2000s, are not always as scary as they seem. On the contrary, they can give rise to new forms of creativity.»

in 2025 we're leaving behind words "graped" "sewerslide" and "unalived" when referring to serious topics you gotta say the actual words like a normal person

— rocinante of wisconsin (@penbbles) January 1, 2025

The problem, however, lies precisely in the fact that this new linguistic register was never supposed to leave the TikTok bubble, landing on other platforms and then in real life. In theory, algospeak was born as an internal strategy to a specific platform, a form of spontaneous adaptation to its rules and automatisms. Yet today, this language is migrating in full force: already on X, many users complain about the now widespread use of algospeak, pointing out the absurdity that precisely that platform — where explicit content is not censored or banned (unless it involves direct criticism of Elon Musk) — has ended up hosting those same linguistic formulas born to evade censorship elsewhere. On Instagram and Facebook, on the other hand, algospeak is not just a trend or a game but also takes on a political dimension. Here, its use often becomes necessary because Meta’s rules systematically hide content related to sensitive topics such as war or human rights, especially when speaking openly about Palestine or ongoing conflicts. As also reported by Human Rights Watch, it is enough to use explicit terms or specific names for a post to be hidden, silenced, or downranked by the algorithm. Between a p4l3s+in3 and a sewer slide, algospeak ends up reflecting not only the digital obsession of a generation that no longer knows how to relate to others, but also the contradictions and political tensions that cross our way of communicating online. Is linguistics about to change forever?