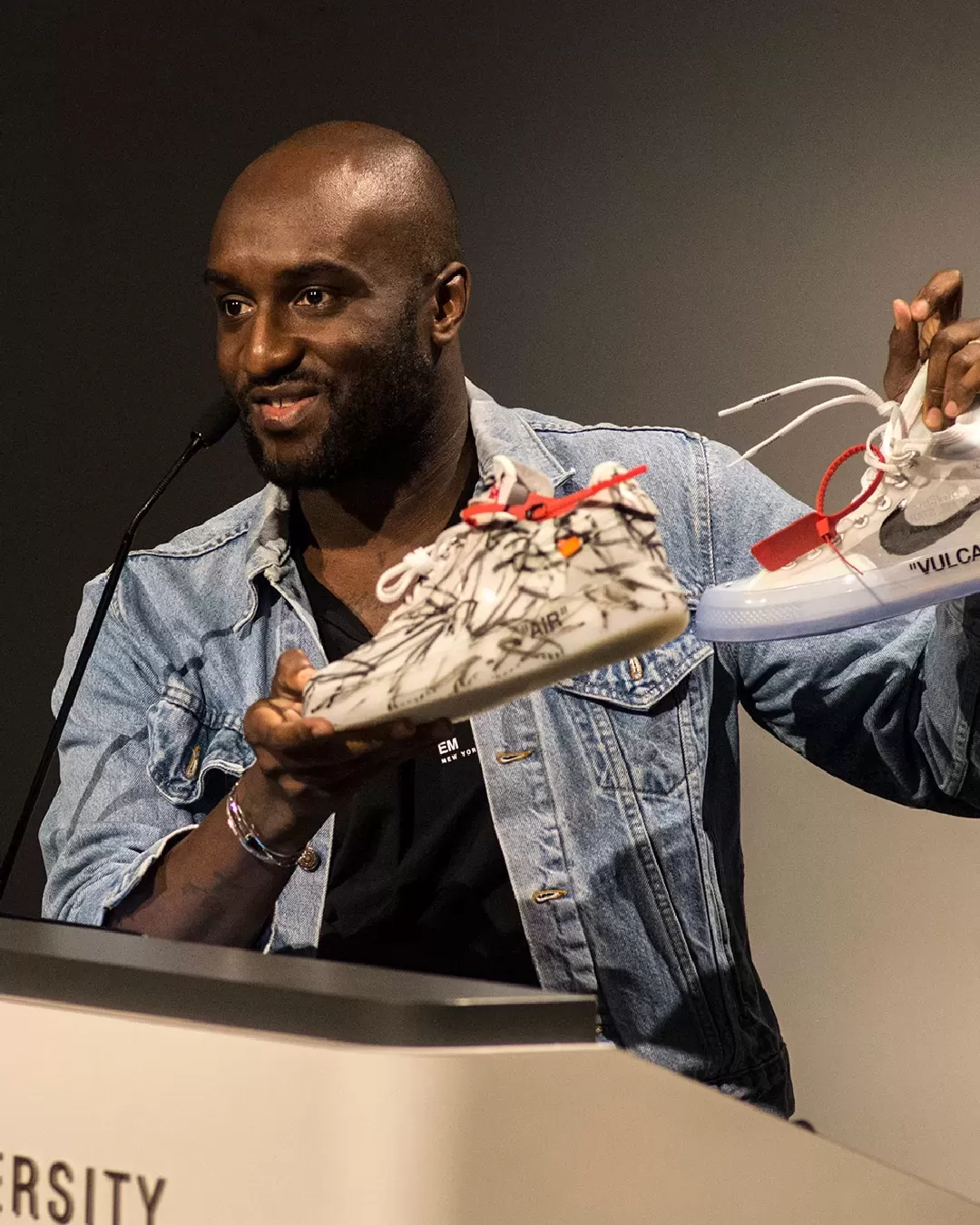

Luca Guadagnino will publish his famous obituaries in a book Those he writes for Corriere della Sera together with Carlo Antonelli

Luca Guadagnino, in addition to being one of the most important directors of his generation, has long been known for the famous obituaries he publishes in the Corriere della Sera together with journalist and film producer Carlo Antonelli. Their brief messages of condolence and remembrance—often marked by a poetic and ironic style—have become so iconic that they are now a very recognizable and eagerly awaited format, especially in the Italian cultural scene. For this reason, the publishing house Sellerio has decided to release the first collection of obituaries written by Guadagnino and Antonelli. Guadagnino himself announced it during an interview with Alessandro Cattelan, on the podcast Supernova. “It was pointed out to me that we had invented a literary genre,” Antonelli tells Cattelan, who contacted him during the conversation with Guadagnino precisely to talk about their acclaimed obituaries. The obituary section of the Corriere della Sera is a “temple of the Milanese upper bourgeoisie”, explains Antonelli, “into which this highly unlikely duo has inserted itself and gradually climbed [...] all the ranks, so that at times we found ourselves right after the family's announcement”. “I must say that the Corriere respects us greatly,” adds Guadagnino.

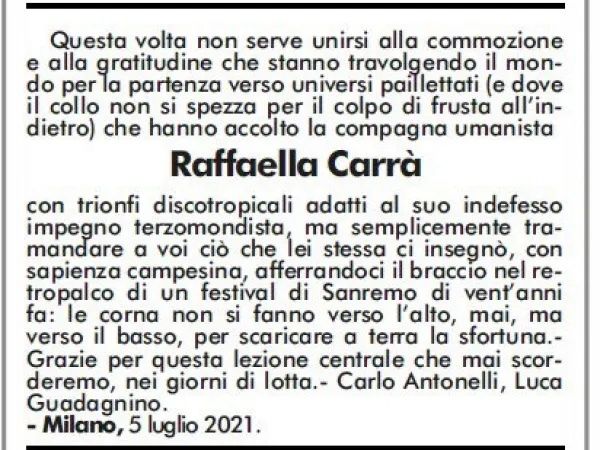

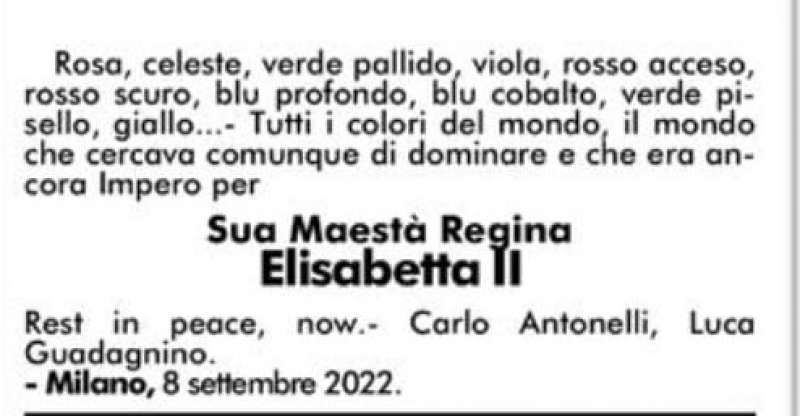

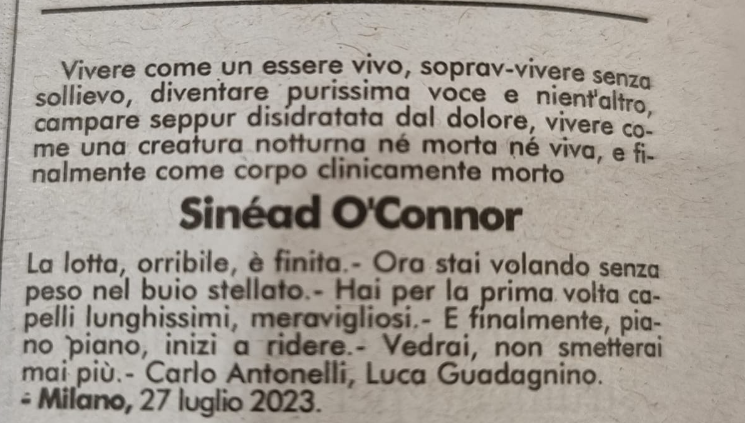

In the past, the duo wrote obituaries on the occasion of the deaths of Raffaella Carrà, director Jean-Luc Godard, Queen Elizabeth, and designer Enzo Mari—the latter being the first of their collaborations. One of the obituaries by Guadagnino and Antonelli that sparked the most discussion was the one dedicated to Silvio Berlusconi, which was divided into two parts and read as follows:

“We walked around Milano 2 all afternoon, thinking of you. The brick-colored houses, the little bridges, the old headquarters of many of your offices, the swan lake where, from time to time, they would offer their final song for you. Then, at the edges, the glimmer of candles behind the windows of gifted homes. And everywhere, in the empty streets, the echo of your laughter. So much laughter... too much. The next day we celebrated you again by playing all your favorite games: the rigged Monopoly without chance or community chest; Scrabble to write elegant little words; karaoke, all dolled up like you to forget every thought; the séance to awaken the demon in the country's belly. We screamed all night.”

Despite the enigmatic tone, the text contains clearly ironic passages, such as the reference to the “rigged Monopoly”—likely an allusion to the ad personam laws promoted by the former Forza Italia leader.

How do obituaries in newspapers work?

I necrologi firmati da Luca Guadagnino hanno il dono della poesia. pic.twitter.com/FXxmDdNXHg

— Umberto Ambrosoli (@uambrosoli) December 31, 2022

Obituaries in newspapers originally began as simple funeral announcements, meant to publicly communicate a person’s death. Over time, however, they have evolved into a tool to celebrate the lives of the deceased within a public and institutionalized space—such as a national newspaper. In major Italian newspapers, obituaries are usually paid and almost always maintain a sober and discreet structure, often very similar in content and form. Usually it is the family members who publish the first notices, followed by those from friends, colleagues, acquaintances, or admirers. Among Italian newspapers, the Corriere della Sera has the most established tradition of publishing paid obituaries. Those wishing to remember a loved one tend to choose the newspaper most rooted in the area where the person lived: it is no coincidence, then, that a large share of obituaries published in the Corriere are connected to the city of Milan, where the newspaper has many readers. The cost of an obituary varies depending on the space it occupies, and therefore on the number of words. Until a few years ago, the price on the Corriere della Sera was about six euros per word. During the Covid-19 pandemic, the sharp increase in mortality in Italy led to a significant rise in the number of obituaries published, confirming how print newspapers—despite the general decline in sales—continue to be perceived as authoritative products, virtually unmatched in the digital sphere. When a particularly well-known figure passes away, the number of obituaries can be surprisingly high, sometimes requiring multiple pages. This was the case, for example, with Milanese entrepreneur Gian Marco Moratti, for whom in 2018 the Corriere della Sera published over 400 obituaries spread across three pages.