Is the new American dream made in China? With both hard and soft power, China is reclaiming its place

In Mandarin, the name by which China refers to itself is 中国, pronounced Zhōngguó, which literally translates to “central land.” A linguistic choice that sounds almost like a self-fulfilling prophecy. Because, in many ways, China has indeed become the world’s most “central” country. Central not only in economic and technological terms, thanks to a steady expansion that has gradually eroded the United States’ industrial supremacy, but also in what is defined as soft power, the force that makes a nation a cultural hegemony.

When we speak of soft power, we refer to the liberal arts, media, and all those cultural products that, as citizens of an ultra-globalized world, we consume daily. For decades, the United States set the rules of international culture – from film to music, from Hollywood’s Hall of Fame to McDonald’s burgers – shaping a shared imagination so pervasive that anyone, anywhere in the world, could recognize its icons. As Pierre Bourdieu explained through the concept of cultural capital, “culture is never merely a terrain of pleasure or expression, but also a field of power where the definition of what is normal, desirable, and universal is constantly negotiated.”

Over the past decade, however, partly due to Donald Trump’s presidency, that collective fantasy of the 1990s and early 2000s tied to the American Dream has begun to fade, or, at least, to shift eastward. According to Statista, in 2024, China welcomed around 26.9 million international visitors, a 96% increase compared to 2023. A figure that speaks to the country’s growing openness and appeal. People no longer talk about Thanksgiving or the Super Bowl, but about moon cakes and the Chinese New Year.

The Brain Drain Reversal

For over thirty years, the direction of the brain drain was clear: from China to the West. Young researchers, engineers, and academics left en masse for the United States, long seen as a symbol of intellectual freedom and economic opportunity. Today, however, that flow seems to have reversed. As America faces growing political uncertainty and social division, and the promise of the “American Dream” weakens, more and more people are looking to China as a credible professional and cultural destination. One that combines economic growth with long-term stability.

This shift is best illustrated by the recent K Visa, launched by the Chinese government to attract foreign talent in science and technology. According to Al Jazeera, the program, announced by the State Council and implemented in September, aims to “promote exchange and cooperation” among STEM professionals worldwide. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs emphasized that this measure is part of a broader reform strategy, including streamlined visa procedures and a redesigned permanent residency card for international professionals.

As Zhigang Tao, professor of economics at the Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business in Beijing, noted, “from the 1980s to the 2010s, China lost talent to developed countries such as the United States. Now the task is to retain local talent and attract new global minds.” A statement that underlines how Beijing is pursuing not only economic competitiveness but also a form of cultural hegemony grounded in innovation and imagination.

Is Shanghai the New New York?

At the same time, as Silicon Valley loses some of its appeal and the U.S. university system becomes increasingly expensive and polarized, with Ivy League schools under constant political pressure, Shanghai, Beijing, and Shenzhen have emerged as new hubs for creative and technological industries. Among them, Shanghai most clearly embodies this transformation: a city that combines economic ambition, cultural dynamism, and a cosmopolitan outlook increasingly reminiscent of what New York represented for decades. A metropolis by definition, Shanghai has long been a crossroads of cultures, not merely a financial center but a place where the new aesthetic and creative codes of contemporary Asia are defined.

Evidence of this is not only the unexpected appointment of Kim Jones as creative director of Bosideng, but also the Shanghai Fashion Week. Its Spring/Summer 2026 edition, held from October 9 to 16, perfectly captures this evolution. As Vogue Business highlighted, the schedule included over one hundred shows, featuring an increasing number of international brands alongside local names celebrating major anniversaries.

If in the 1990s New York was seen as the capital of bold fashion, led by a generation of designers like Marc Jacobs, Anna Sui, and Isaac Mizrahi who challenged the rigidity of other cities, today that same energy seems to have moved to Shanghai. Designers such as Mark Gong, Shushu/Tong, and AO YES are redefining the boundaries between Western aesthetics and Eastern sensibilities, presenting collections that blend irony, romanticism, and social commentary, making traditional fashion weeks feel increasingly obsolete.

What truly sets this new wave apart is the conscious decision to remain in Shanghai rather than seek validation in more “central” circuits like Paris or Milan. It is a form of cultural and creative independence that marks a shift where one no longer needs to leave to be recognized, because the center of global attention has already moved home. And if New York now struggles to compete with London, Milan, and Paris, it’s fair to ask whether, in a few years, it might be Shanghai that officially takes its place.

China’s Image Has Changed (for the Better)

@digital.god You met me at a very Chinese time in my life #china #chiense original sound - Lionstowth

Beyond fashion, the same shift is visible on social media. “You met me at a very Chinese point of my life” is the latest trend going viral on TikTok, alongside phrases like “everyone get more Chinese now” or “spiritually Chinese.” None of these expressions carries a negative connotation; on the contrary, they signal a renewed fascination among Western audiences with China. A striking reversal of the sentiment that has dominated the past two decades, especially in the United States.

In a video essay published two years ago titled China Has a Soft Power Deficiency, creator @aini argued that compared to South Korea and Japan, China had yet to find its own “cool factor,” hindered by years of American Sinophobic propaganda and the global success of K-pop and anime, which had made those two nations highly desirable in Western eyes. Today, however, that comparison no longer holds.

The turning point came with the digital diaspora triggered by the potential TikTok ban in the United States between late 2024 and early 2025, which pushed thousands of American users to migrate to Xiaohongshu (Rednote). Many soon realized how deeply their perception of China had been shaped by negative media narratives. A tweet that went viral at the height of the debate early this year read, “Not only do I willingly give my data to China, but I also freely give my heart,” amassing over 1.3 million views and 57,000 likes.

Not only do I willingly give my data to China but I also freely give my heart

— Kat (@albertcamslut) January 14, 2025

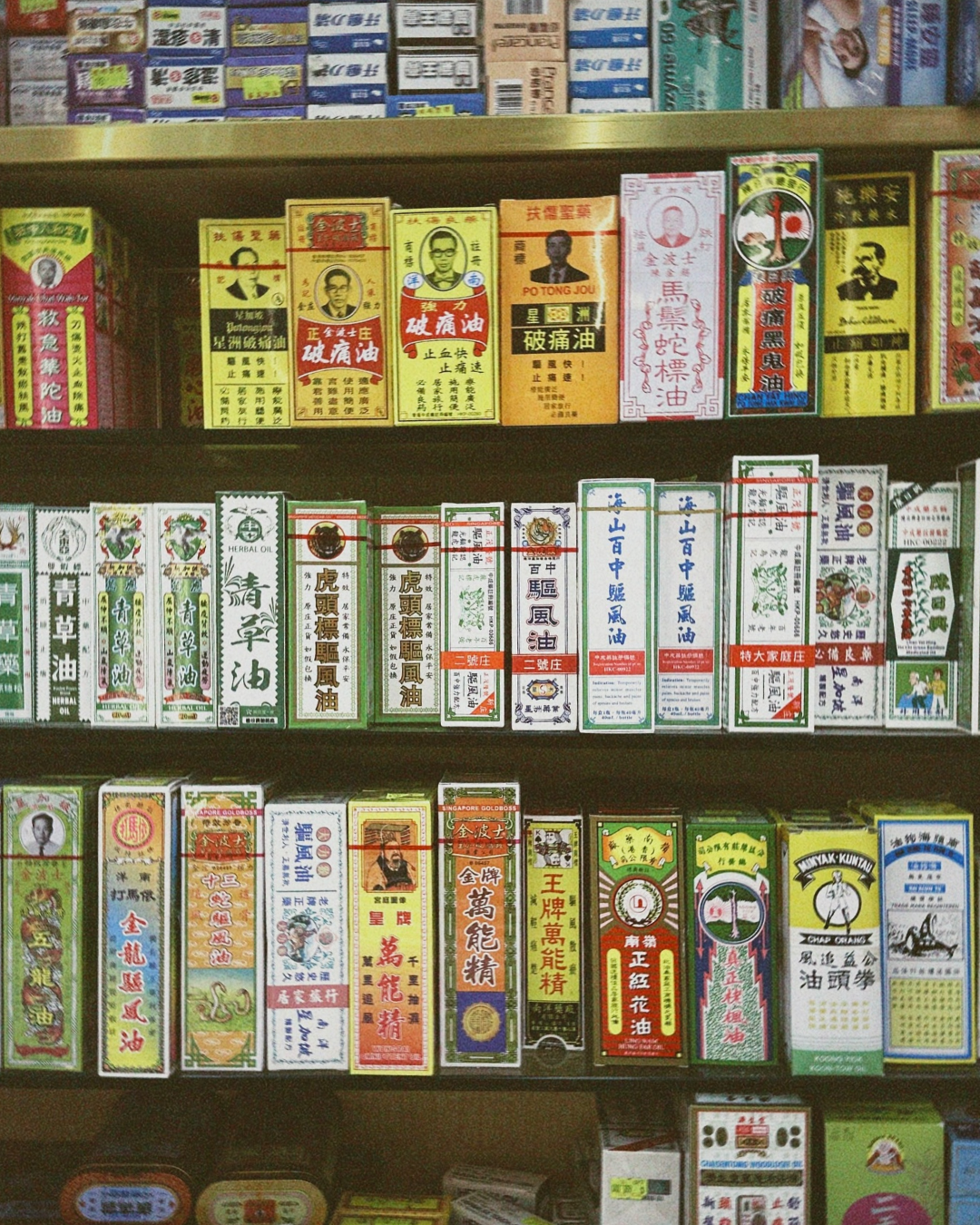

Today, Chinese pop culture is not only part of the global conversation but is actively leading it. From romantic dramas to xianxia fantasy series and games like Genshin Impact, China is redefining the parameters of soft power. The most recent example is the rise of Labubu, the small characters created by Kasing Lung and produced by Pop Mart, which in just a few months have become one of the most viral cultural phenomena of the past decade.

The American Dream was born from the desire for individual freedom. But the Chinese one emerges from a sense of collective identity that has learned to turn its culture into a universal language. And if, until recently, it was the West dictating global taste, today the world seems eager to learn Chinese. Perhaps it’s simply time for the country to fulfill the role foretold by its own name.