Is Pitchfork about to become our new favorite social media platform? Perhaps not, considering the $5 per month it charges

Last week Pitchfork, the most famous online music magazine in the world, made a historic announcement: starting this year, the use of the site will no longer be completely free, but there will be a monthly subscription of 5 dollars (about 4.40 euros). Essentially, this is the introduction of a mixed paywall that will still allow access to the site for free, but with some important limitations.

For a site that was born with the idea of embodying independence and a certain level of openness in the music world, this is yet another major change in its long history, which this year reaches thirty years.

The history of Pitchfork

Pitchfork, which takes its name from Tony Montana’s tattoo in Scarface, was born as a blog in 1996 on the initiative of Ryan Schreiber, who at the time was still a teenager working in a record store in Minneapolis. One day he had the intuition to try to take advantage of the potential of the internet to do more or less the same things he did in the store – namely recommending or discouraging music – but this time through the format of the written review.

The initial idea was to focus mainly on alternative and independent music, belonging to what once fell under the so-called macro-genre of indie rock, and then expand to all other genres once a certain level of notoriety was reached. Year after year, the blog became increasingly popular thanks to an irreverent writing style, much more daring than that used by traditional print music magazines, reaching its peak with the famous review of Jet with no text, containing only the video of a monkey peeing on its own head while drinking its own urine.

The episode is so iconic that it was also referenced in the official announcement of the new era of Pitchfork published on the site, where at one point it says that Pitchfork’s reviews «can sometimes feel like the final word, a monkey peeing into its own mouth carved on a stone tablet.» It is worth noting that even back then – it was 2006 – Pitchfork was no longer a small amateur blog, but in ten years had become a reference point for online music criticism.

The importance of Schreiber’s reviews

The transition from a blog to a relatively professional publication took place in 2004, with the arrival of Chris Kaskie (The Onion) to manage commercial operations and Scott Plagenhoef joining the editorial team (now global head of editorial at Apple Music). The authority of its reviews had become such that it could now determine the success or failure of a band.

Some stellar scores, for example, made the fortune of groups such as Arcade Fire (9.7 for Funeral), Animal Collective (9.0 for Feels) and The National (8.6 for Boxer). This ultra-specific evaluation through a decimal numerical system from 0.0 to 10 became its trademark and at the same time a blessing and a curse: on the one hand this distinctive pseudo-scientific trait attracted attention and set a trend (in Italy, for example, it was adopted by one of the main independent music sites such as Sentireascoltare), while on the other it opened itself up to mockery by the so-called serious criticism of traditional print media.

An unconventional rating system

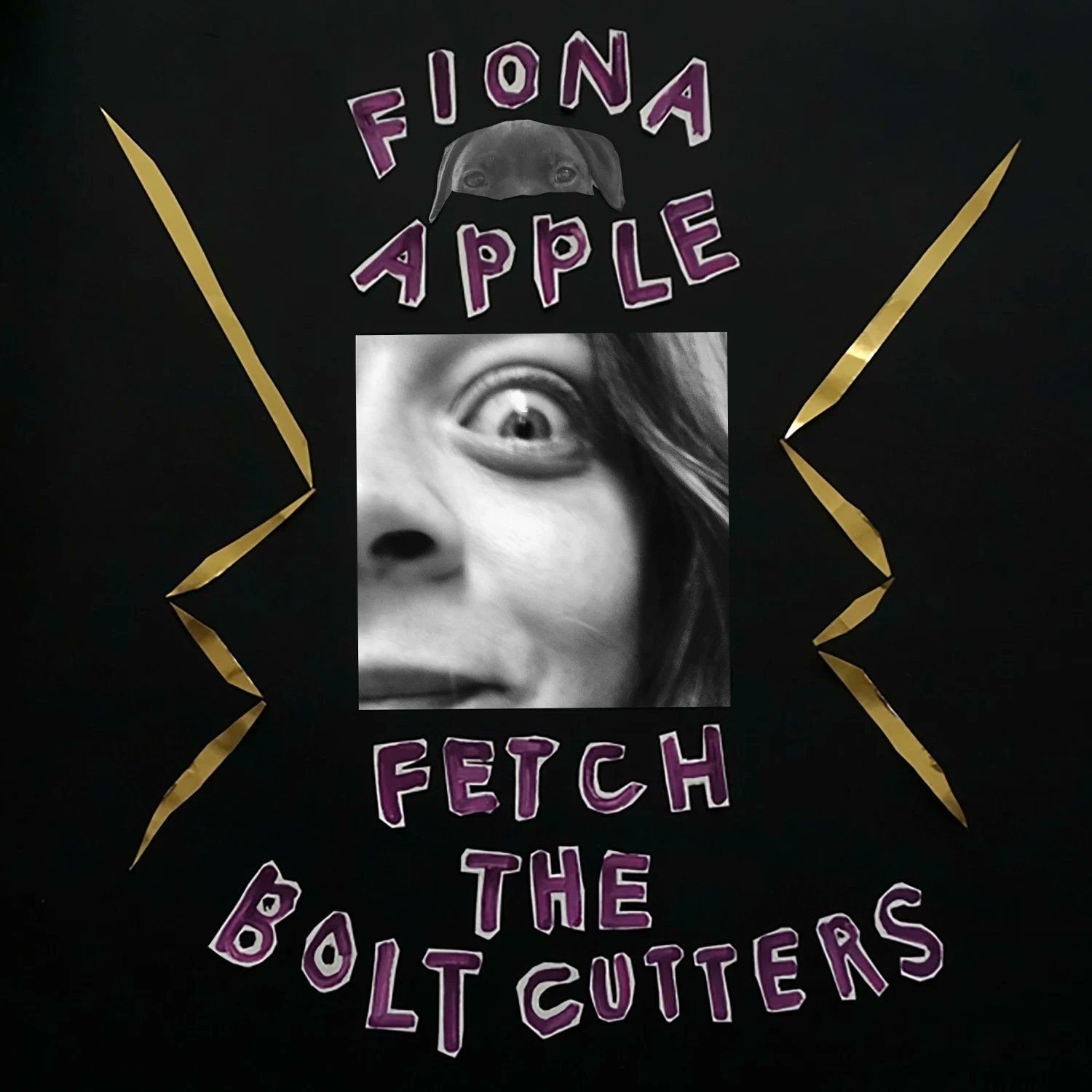

The review system of Pitchfork has turned the site into a true trendsetter in online music criticism. A high score on the platform has often been able to heavily influence the judgment of other outlets: the most striking example was the 10 awarded by J. Pelly to Fiona Apple’s album Fetch the Bolt Cutters, which went on to generate an almost unanimous verdict of an absolute masterpiece from other music sites.

Over the last ten years, the management events of Pitchfork have begun to cast a series of shadows over the site. The first blow came in 2015, with the sale of ownership to the media giant Condé Nast (Vogue, Vanity Fair, New Yorker, etc.), which effectively marked the end of its independent spirit as we knew it. Then in 2024 Anna Wintour announced the layoffs of part of the staff and the merger of the remaining team of Pitchfork into that of GQ. Some journalists belonging to the Pitchfork diaspora founded the new music site Hearing Things, which, not by chance, is paid.

What the Pitchfork subscription includes

For the first time in 30 years, we’re launching a digital subscription. Read every Pitchfork review, rate and review albums yourself, and take part in artist and editor Q&As, all for $5 a month

— Pitchfork (@pitchfork) January 20, 2026

More info: https://t.co/1m1gdALL2P pic.twitter.com/tRdfn1JbuN

The announcement on social media and on the site focuses mainly on highlighting the new implementations, namely all the new features of the site that should encourage users to subscribe. These essentially consist of two points.

The first is the possibility for paying users to express their own numerical judgment on the album in the same historic Pitchfork format. For this reason, convenient guidelines have been published to understand, for example, the difference between a score of 6.8 and one of 7.1. Once a review has reached more than five user ratings, the average reader score will appear below the Pitchfork score in the review.

The second is the possibility to interact in written form, that is, to comment on reviews directly on the site, establishing a dialogue with other users or directly with the editors. Essentially, this is a process of platformization that makes P. a hybrid between a music site and a social network or an old-style forum.

Pitchfork shares its rubric on how they score albums. pic.twitter.com/eRCHc5YByx

— Pop Crave (@PopCrave) January 20, 2026

All things considered, this is nothing transcendental or particularly innovative: comments have already existed for years on other competing sites, such as Stereogum, while the possibility of rating an album has always been the core business of other famous sites such as Rate Your Music, so widespread that it already collects thousands of ratings per album. On RYM it is also possible to comment on and review the albums you rate. The same goes for other well-known aggregators such as Metacritic or Album Of The Year. There is, however, a dark side to this subscription that is not highlighted in Pitchfork’s announcement, but is mentioned almost in passing while actually constituting a third fundamental point of the matter:

The paid subscription is the only way to continue reading all the reviews on the site — an archive of about 30,000 articles — without any limitation; otherwise, free users will only have access to four reviews per month. Pitchfork specifies that all the other sections of the site — news, lists, and in-depth features — will remain fully accessible for free. The limit applies only to reviews, which, as widely illustrated, are what made Pitchfork successful.

Reception and criticism from the public and industry insiders

As expected, the news sparked a wave of negative reactions from users, since generally no one is happy to pay for what used to be free. Moreover, the new implementations do not seem to guarantee that minimum added value sufficient to justify the expense. The comments on the Instagram video announcement include a series of insults ranging from the classic «booooooo» to memes, all the way to critical ratings expressed using the same decimal numerical formula, such as «0.0 – 1.0.»

Among the various insults there are also some more or less reasonable criticisms. The most visceral ones are connected to the Condé Nast affair, since the average Pitchfork user has no intention of giving their money to a multinational corporation headquartered inside the One World Trade Center, one of the most expensive buildings in New York. It is significant that people are making this argument for a music website and not for the New Yorker, just to mention another Condé Nast publication that applies a paywall to its content. This is probably due to a different audience, considering that the young and teenage readership of Pitchfork is unlikely to have the same financial means as New Yorker readers.

What do former Pitchfork editors think?

I would’ve been too broke for a Pitchfork subscription on my Pitchfork salary

— Jessica (@JessicaSuarez) January 21, 2026

Other, more moderate criticisms concern the fact that this system will do nothing but summon swarms of stans (the most hardcore fans) whenever their favorite pop star’s album gets trashed. Just think about what swifties (Taylor Swift fans) or the BTS ARMY might do in the face of a brutal takedown. For journalist Stuart Stubbs (Loud & Quiet), the mistake they made was keeping the rest of the site open to everyone: «Pitchfork’s reviews are great, but are they the only reason you visit the site?»

The same opinion is also shared by former Pitchfork editor Larry Fitzmaurice, according to whom this is «a tacit admission that the rest of the site’s work is not worth paying for and is therefore of lower quality.» Steven Hyden — also a former Pitchfork writer and author of several music books — adds that these somewhat unstable parameters seem to suggest that P.’s mixed paywall gives more importance to scores than to articles.

On cooler reflection, the use of paywalls is actually nothing new for foreign online music magazines: Rolling Stone USA, for example, has been charging a subscription to read its articles for years. The same also applies to other small and independent outlets that otherwise could not survive, such as Aquarium Drunkard or the aforementioned Hearing Things.

A better solution

does anyone wanna fall in love in the pitchfork comments section

— eli (@elischoop) January 20, 2026

Another historic music magazine such as Creem (the one Lester Bangs wrote for) has returned online in recent years behind a paid subscription. Other publications in some way competing with Pitchfork, such as Stereogum and The Quietus, have long since introduced paid sections through a mixed system similar to Pitchfork’s, but with the opposite logic. The two sites in fact maintain free access to historical reviews, while requiring a subscription to access new columns or special content. In this way, they guarantee basic access for all users and paid in-depth material only for true enthusiasts, presumably those more willing to spend their money to learn more.

This appears to be a more moderate solution compared to the one adopted by Pitchfork, which is instead much bolder, as it suddenly makes less accessible what has always been its beating heart. It is certainly a challenge, and nowadays it is impossible to make long-term predictions. What is certain is that in the music world, surviving online as a text-first outlet without any kind of subscription seems to be increasingly difficult. We will see whether Pitchfork’s choice will be a commercial suicide leading to the site’s collapse, or whether it will once again turn it into a trendsetter, gradually making all online music magazines paid.