“Felicità” is the exhibition that celebrates the ordinary Italy through the lens of Luigi Ghirri

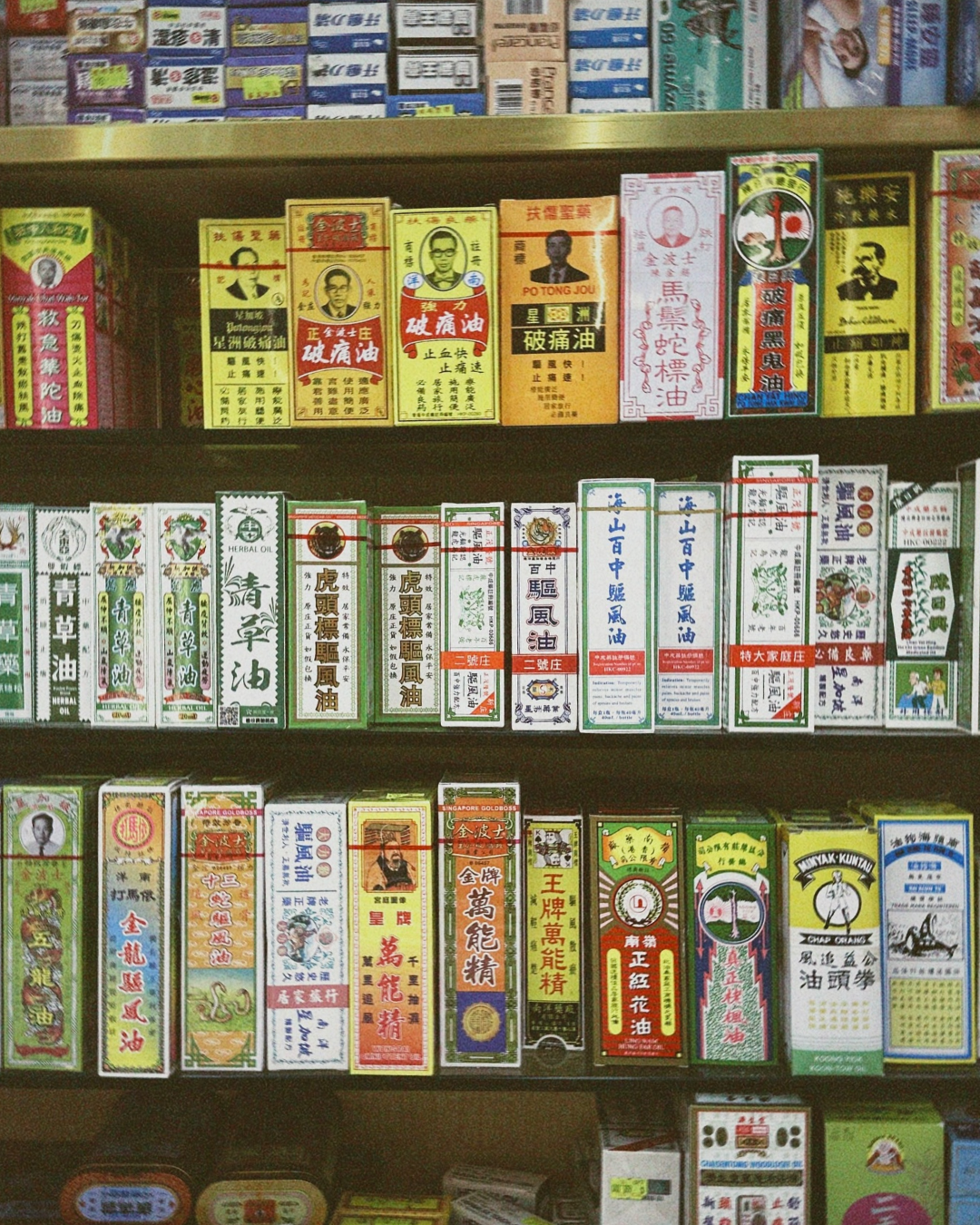

Ghirri’s photographs nearly take us back to 2016. Being online during the noughties was to embody vagueness in one’s gaze towards the world, where the most unassuming objects like fish for sale graced visual artist Sara Yukiko’s feed, while downtown girl Manon Macasaet, emerging onto the New York creative scene, was posting inflatables blowing in the air. It’s a similar effect one feels while viewing Ghirri’s Italy lined up on the walls of Thomas Dane Gallery as part of "Luigi Ghirri: Felicità" as we follow the artist’s calm gaze from the sidewalk to a street sign as it shifts through the ordinariness of the everyday.

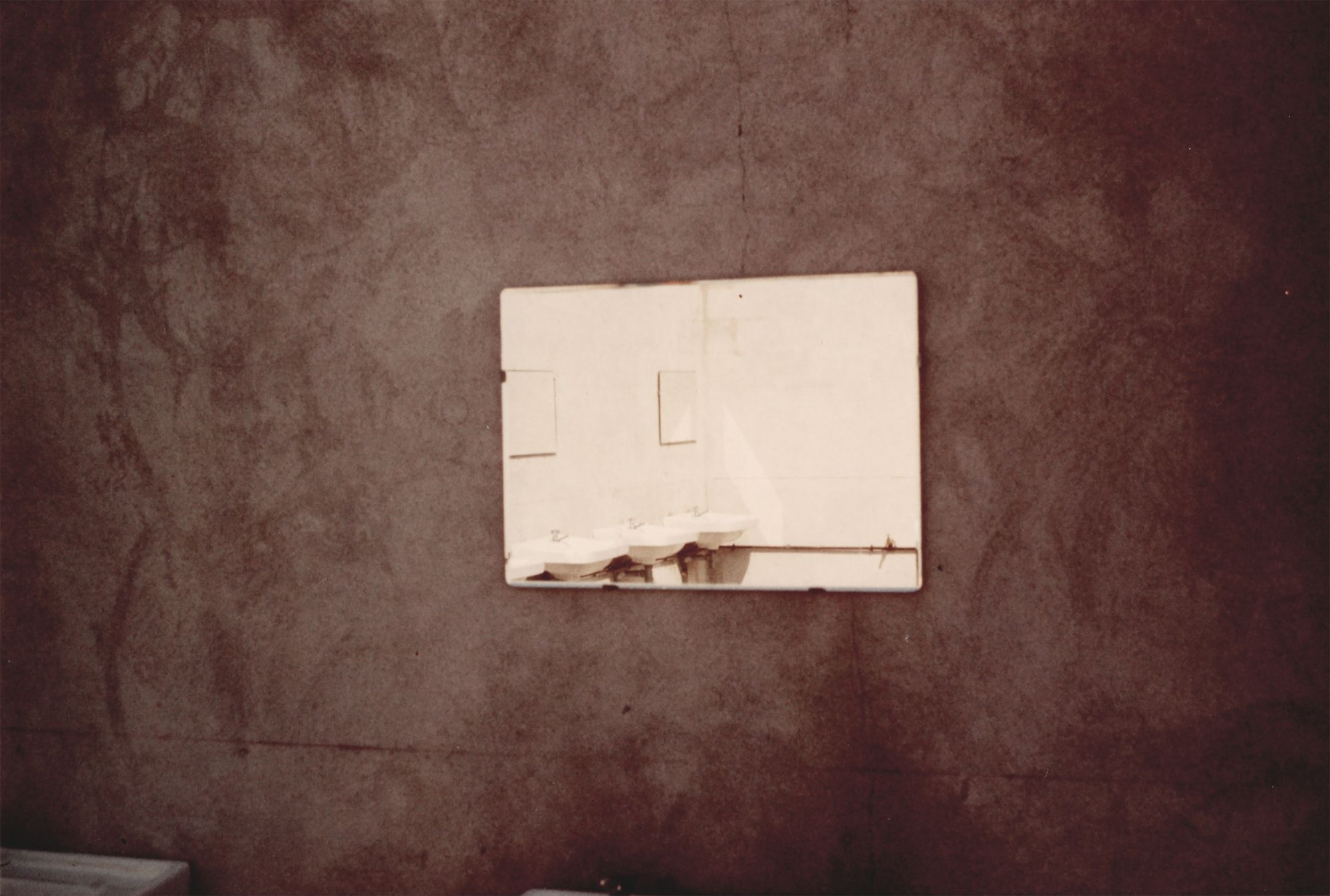

It’s an exercise in walking around Modena with Ghirri that we participate in – even decades after he took the photographs in the early ‘70s before he quit his job as a surveyor. For someone who was intimately familiar with postwar Italy, whose landscape had changed irrevocably after Mussolini, Ghirri’s Italy strangely blends into the universal with brown brick laid walls or spray-painted surfaces – cropped as if to hide the totality of what the object really was. They could even be from today, for that matter.

A walk with Luigi Ghirri

«I wonder why Ghirri insists on rummaging through the densely populated neighbourhoods of our cities with his camera, forgetting about the old squares, whose stones, charged with memories, are part of our childhood,» wrote Franco Vaccari in his survey of the artist’s work. His vistas of a kitschy neon-tinted bar sign or people sitting around in a waiting room generates an alternate visuality from the sharp black-and-white “decisive moment” of Henri Cartier-Bresson whose picture-perfect snow globe Italy was dominated by women in billowy skirts against the backdrop of a city which unraveled like a theatrical set – or men in suits wolfing down pasta – which remain metaphors for commercial photography to take delight in referencing.

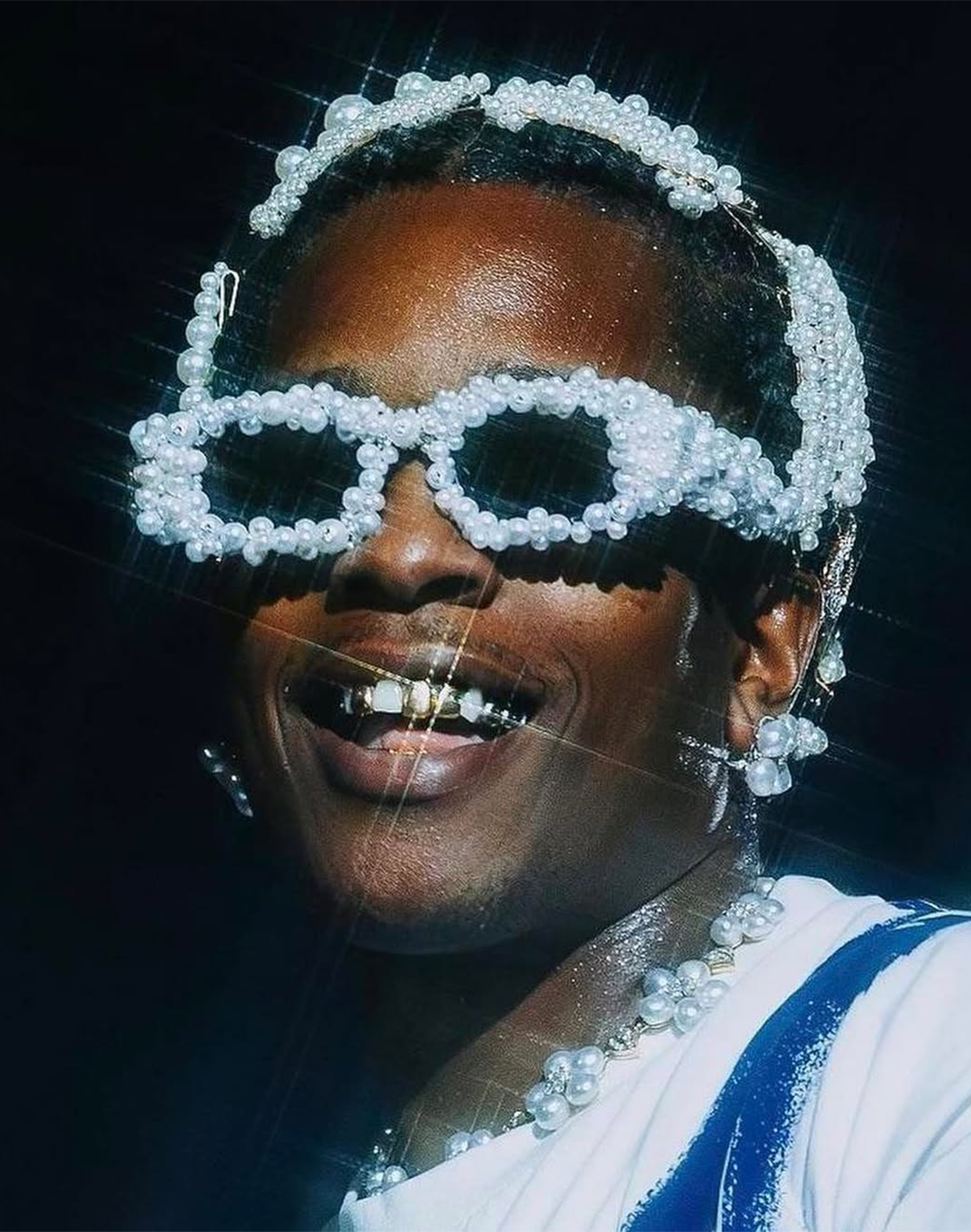

Ghirri’s work finds resonances with his contemporaries like Guido Guidi and Stephen Shore, photographing the nondescript and the mundane, like a parking lot. Ghirri was a rare butterfly during Italian avant-garde of the ‘60s and ‘70s, writes curator Tobia Bezzola – and that was true even with him choosing his prints to be in colour, which was then used only in advertising – to emulate the tones of billboards and prints in popular magazines. Most images are formulaic cliches, he wrote in an essay reprinted in the accompanying exhibition book by MACK. «I choose images on public display,» the artist would write in his first seminal publication, "Kodachrome" «In the streets, in shop windows etc. - in order to charge them with an emblematic, symbolic value, and a degree of complexity that cannot be reduced to schemes or formulas».

In a photograph from "Modena", a child’s fashion advertisement distorts as it tears apart, revealing bricks on the wall – but that reveals itself to be a trompe-l’oeil illusion, through which Ghirri continues his narrative on representation and distance from reality that causes. Their inclusion also cheekily points towards one of the curators, along with Luca Guadagnino – image-maker Alessio Bolzoni’s own extensive work in fashion.

Documenting Change

Ghirri would collect illustrated postcards – not the advertising kind – but ones which simply documented development in the changing Italian landscape. In many ways, the segment of the exhibition with his later works is reflective of that, where Ghirri stops at a nondescript bus stop or looks up at the sky with a couple of marble sculptures in the backdrop – in an attempt to diminish their touristy significance.

There’s quietness in his photographs – more so as this selection is often devoid of people, or where its human inhabitants are reduced to minuscule objects like dolls in a toy town – almost like the stillness of Giorgio Morandi’s objects he photographed in the fine artist’s studio after his death. Car parking spaces and amusement parks seeped in the bright lights of early consumerism, which now appear nostalgic, and maybe Ghirri predicted that.

«Ghirri was not a photographer but an artist that used photography,» reflected Bolzoni. The gallerist Germano Celant agreed, mentioning how photography becomes a philosophical tool for capturing the strange and unusual qualities of thought for Ghirri. The exhibition doesn’t look for the perfect shot, elaborated Guadagnino, as Ghirri himself didn’t want that. «It shows the logic and function of one of the most poetic artists of the 20th century» he said.