Is the male body truly free on the runway? Marketing, inclusivity, and new forms of objectification

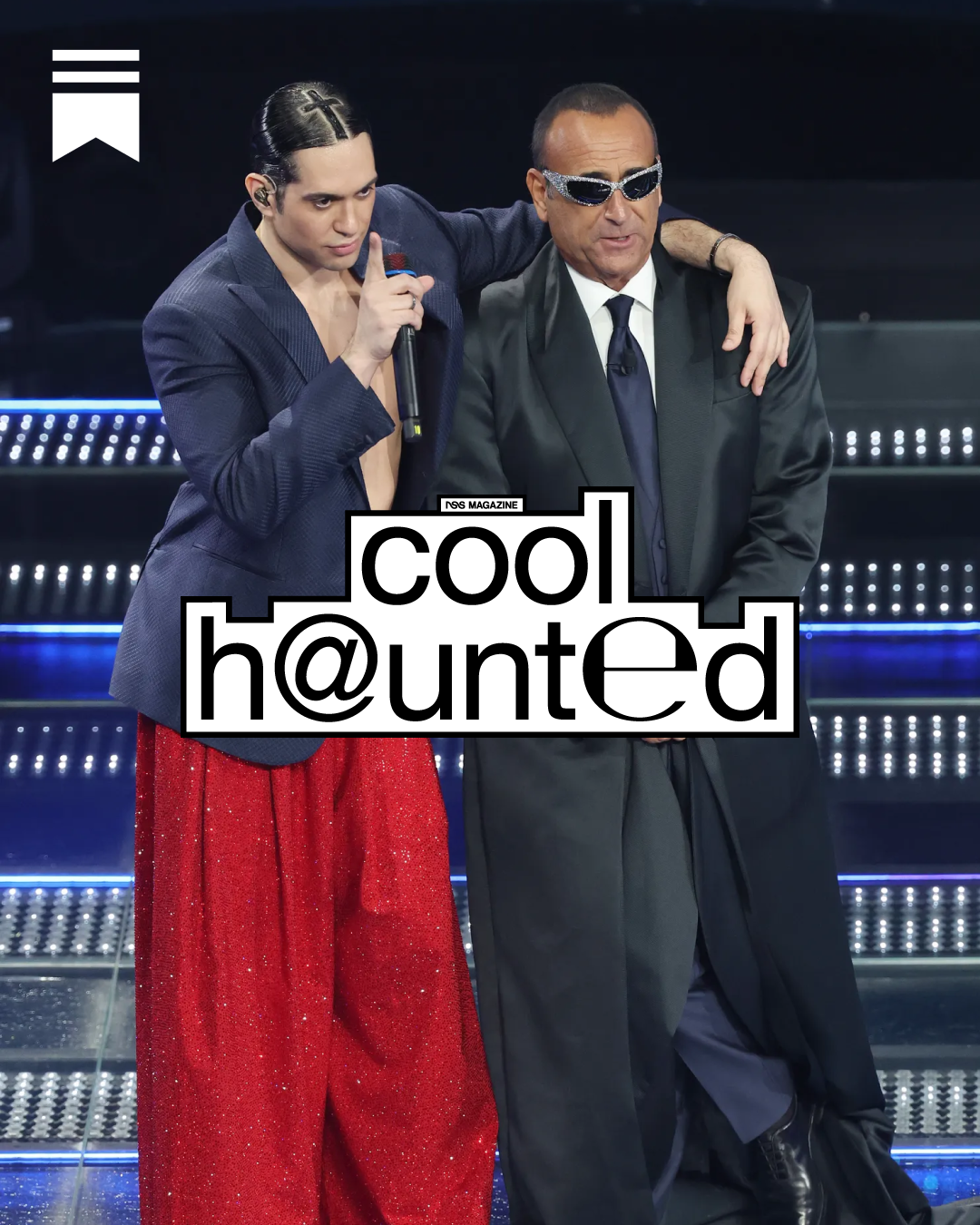

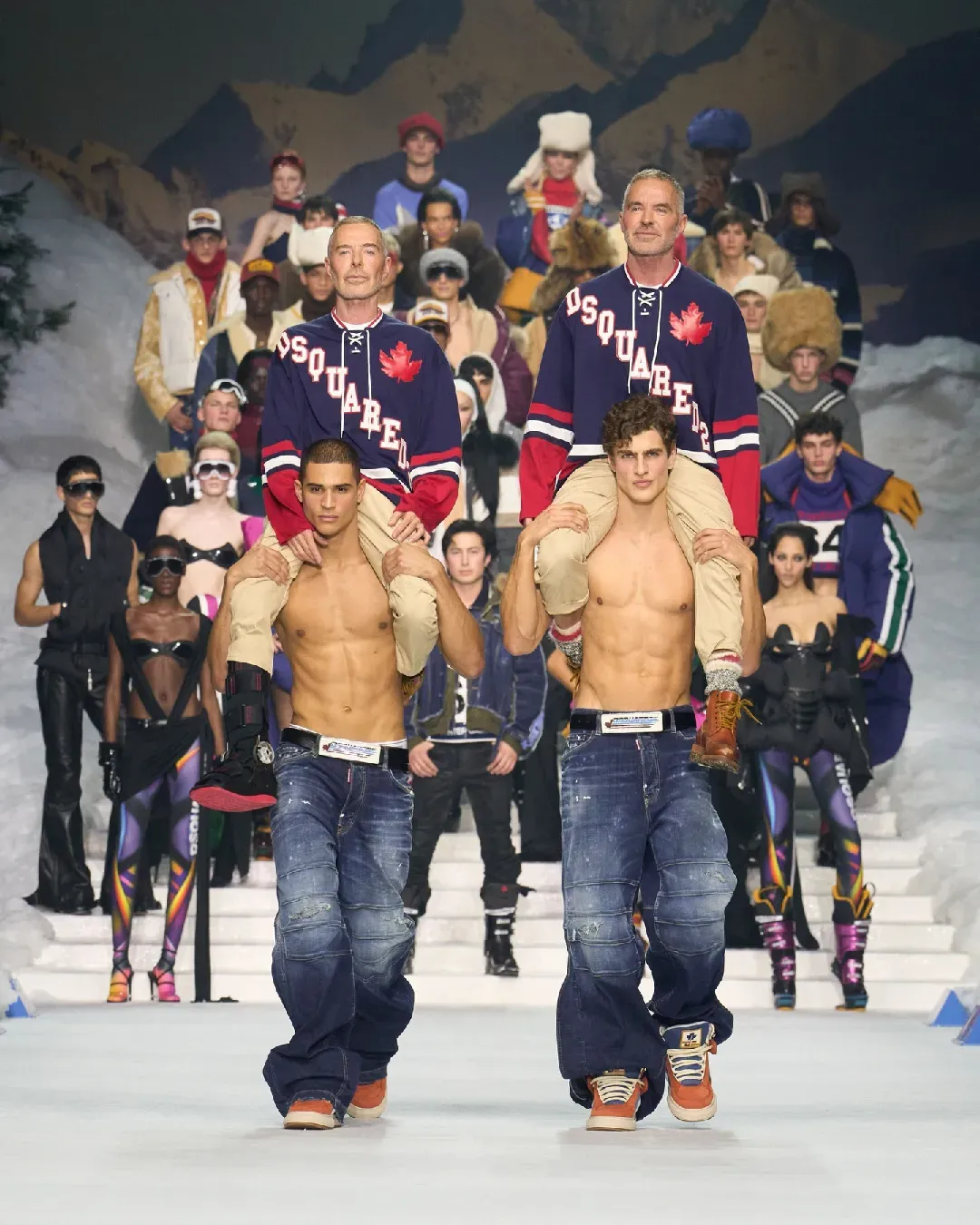

Talking about fashion also means talking about bodies and, usually, talking about bodies also means addressing sex. Feminist movements, with #MeToo leading the way, have brought into public view the issue of the sexualization of the female body, portrayed everywhere as a mere object of desire. Yet during the last men’s Fashion Week, Dsquared2 closed its FW26 show dedicated to Canada and hockey with creative directors Dean and Dan Caten carried on the shoulders of two young shirtless models. Images that, in some way, are accepted and even celebrated. Would we have the same reaction if similar performances involved the female body?

The male body between immunity and inattention

Donald Braho, Head of Men’s Division at Wonderwall Management, acknowledges a substantial difference in how the male body is treated compared to the female body in advertising campaigns. «The female body has always carried greater sensitivity and moral tension: even a small exposed detail can spark controversy. The male body, instead, has enjoyed a sort of immunity, until things enter explicitly sexual territory.»

A clear example is the reception of the black-and-white images of Jung Kook, member of the South Korean group BTS, Bad Bunny and Jeremy Allen White wearing Calvin Klein underwear. «That said,» Braho continues, «there are cases in which the male body has also been used in an almost dehumanizing way, recently in shows that evoked a superficial, excessive, deliberately trash imagery. It’s different when eroticism is built through artistic language. I’m thinking of certain Dolce&Gabbana campaigns photographed by Steven Meisel: there, eroticism recalls classical sculpture, timeless photography. It’s not fast consumption, it’s structured aesthetics.»

@onetruemaverick LLTN attempting to ascend via looksmaxxing: Day 7/100 #looksmax #viral #tiktok #fyp #mog original sound -

The sexualization of the male body has long been a marketing tool used to generate profits. One only needs to think of the success of Abercrombie & Fitch, built on young men with sculpted chests and abs employed as greeters at the entrance of its stores. Today, however, something seems to have changed. First of all, the language used to portray the male body. «Major brands often use a more direct eroticism, especially in fragrance campaigns: the charismatic actor, the seductive gaze, the athletic body. It’s a clear language,» explains Braho. «Independent brands, on the other hand, often work with a more conceptual eroticism or one influenced by queer culture, which has now become mainstream. The principle hasn’t changed, but the cultural context in which it is received has.»

The second aspect is aesthetic. After years dominated by the slender bodies of indie singers, the models of Hedi Slimane and skinny jeans, sculpted and athletic physiques are making a comeback. There has been a shift toward a sensuality that is not spontaneous but trained, disciplined, controlled: «It’s not just an aesthetic issue, but also an attitude in front of the camera. Today, more body awareness, greater image control, and stronger performative ability are required. The model is not just a support for the clothes: they are part of the narrative,» Braho states.

What does the representation of the male body indicate today?

@nssmagazine Dean and Dan closing the DSQUARED2 show in Milan. #dsquared2 #tiktokfashion #mfw #deananddan original sound - hails

The spread of the so-called slutty outfits trend on TikTok suggests that the sexualization of the male body today provokes more laughter than reflection. Videos are created by both men and women and target audiences that are both heterosexual and queer. The gaze no longer has a gender or a sexual orientation. «Male sexualization today is universal because the market wants to speak to everyone: women, men, and queer audiences. It is an inclusive but also commercial strategy,» confirms Braho.

But speaking to everyone does not mean convincing everyone. Take the advertising campaign for the new Jean Paul Gaultier fragrance, Le Male in Blue, featuring a «sex symbol wearing fucking tight pants» consistent with the brand’s provocative aesthetic. However, in a world that demands greater caution and awareness around the body and sexuality, provocation risks becoming a useless accessory, a meaningless affectation. In an ecosystem dominated by algorithms, the male body thus becomes a device optimized for visibility.

When seductive representation collides with stereotypical images, contact with a highly layered reality is lost. Masculinity, after all, is nothing more than a cultural construct in constant evolution. «I don’t believe masculine energy can be erased or rigidly fixed into a single form. There is beauty in fluidity, but also stability in what remains recognizable as masculine. The balance lies in not losing depth while trying to sell,» Braho emphasizes. It is within this context that the hyper-sexualized representation of the male nude slips into objectification: «Fashion is a sector strongly driven by queer creatives, and it is natural that certain codes have become central. The difference lies in doing it consciously, not as an unconscious reaction,» adds Braho.

What do those directly involved think?

@tom.croci One day with model #model #fashion #menstyle #stylish #modeling #models #boss Suddenly I See - KT Tunstall

Those who truly understand the professional implications of this exposure are the people who work in front of the camera. Greater exposure of the male body can be seen as a job opportunity, a pressure, or a new form of objectification: within this delicate dynamic, the role of the agency is key in protecting its talents. «I never place my models in situations where they don’t feel safe. Some are completely comfortable with nudity and others are not. Some have personal, cultural, or religious limits. It is always a case-by-case discussion,» Braho explains. This precaution, however, does not represent a widespread practice: alongside agencies ready to defend their talents, there are others willing to be less scrupulous in acting as intermediaries between brand demands and their models. This only reinforces the image of an industry detached from clear behavioral standards.

Accepting controversial jobs represents significant risks for models, especially newcomers, including permanently associating both the talent’s and the agency’s image with lasting labels. Perhaps, then, the question is not whether the male body is being objectified more than before, but what kind of narrative is being built around it. In an era where the boundaries between genders, desires, and aesthetic codes are increasingly fluid, the representation of the male body becomes a mirror of contemporary cultural tensions. Between queer aesthetics turned into trends, the return of physical discipline, and masculinity optimized for the algorithm, the contemporary male body has never been so exposed, so regulated. It can be emancipation, it can be market logic, it can be both. The difference lies in the intention between a body used to sell and a body capable of telling something more complex. Or, as Braho puts it, «value or noise.»