The naive freshness of surfwear brands in the 2000s When Italian Millennials dreamed of California

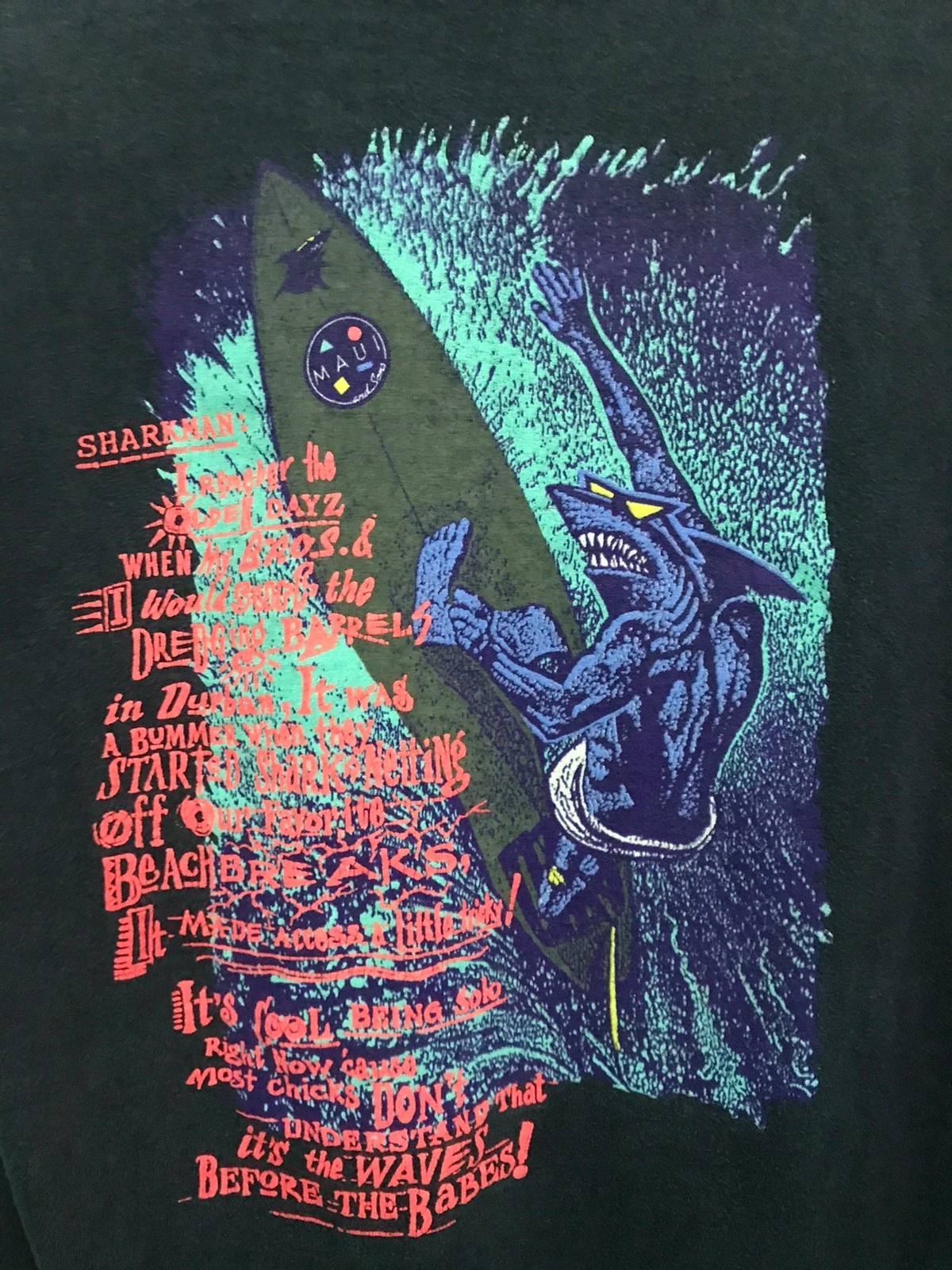

There was a time, between the late '90s and early 2000s, when the wardrobes of Italian teenagers filled up with t-shirts covered in sharks, surfboards, flowers, Mexican skulls, and sunsets over the sea. The success of this wave can be attributed to a group of early streetwear brands that took Californian and Hawaiian surf culture and turned it into a pop, energetic, and vaguely aggressive imagery. Maui & Sons, Scorpion Bay, Billabong, and Quicksilver were the main ones, but we could also mention the more obscure North Shore, Piko, Gotcha, and T&C Surf. These brands shared not only a surfing spirit but also a taste for vintage or futuristic lettering, influences from the “tribal” tattoos of Leo Zulueta and Ed Hardy popular in the '90s, and a call to summer and exotic worlds that evoked a sense of adventure and adrenaline. The iconography typified by these brands drew from the settings and cultures of the South Pacific, filtered and reinterpreted through the lens of American-style commercial fashion whose “tropical” visual theme and edginess (imagine the robotic sharks of Maui & Sons that seemed to roar on the prints of the famous t-shirts) became a kind of symbol for Millennial-generation teens, leaving unsuspected traces in their future.

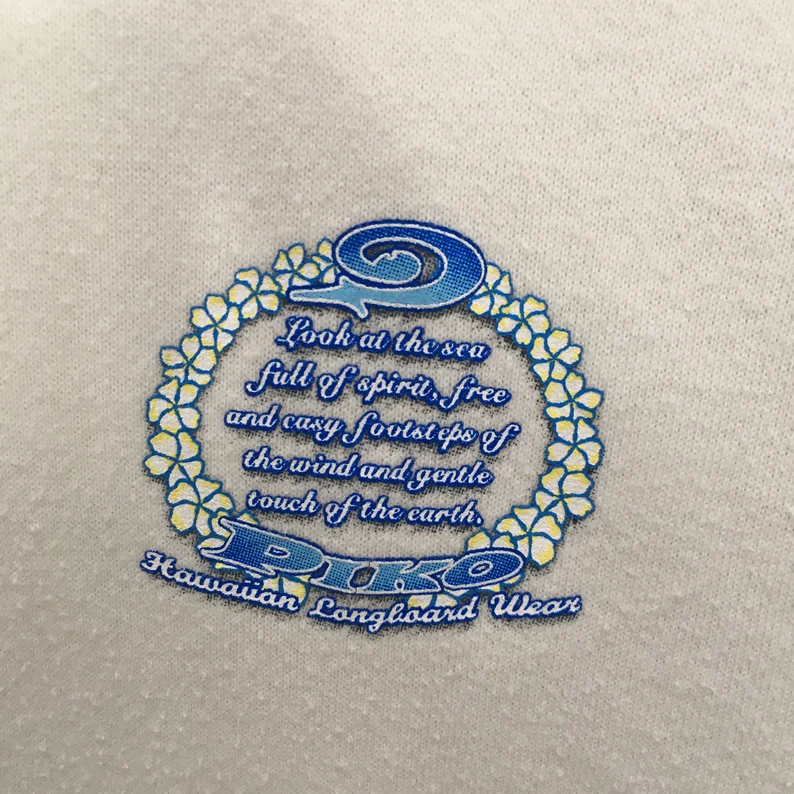

It would be impossible, in this overview, not to mention the brand that reinvented surfwear: Stüssy. At the time, however, it still didn’t enjoy, at least in Italy, the cult status it has today. Both Stüssy and these surfwear brands share the same time and place of origin – often centered around international surf hubs and the ’70s/’80s decades, give or take a few years. Quicksilver, for example, was founded in 1969 in Torquay, Australia; T&C Surf Designs was born in Pearl City, Hawaii, in 1971; in 1978 Michael Tomson and Joel Cooper founded Gotcha in Laguna Beach, whose graphic designer was none other than Shawn Stussy; Billabong was born two years later in Queensland, also in Australia; after leaving Gotcha, Shawn Stussy founded his eponymous brand in Laguna Beach in 1980, the same year Maui & Sons was founded in Malibu; Scorpion Bay was founded by two Californian surfers in 1987; while in 1994, in Honolulu, Kevin Kamakura and Wade Morisato founded Piko. The last in line is Hollister, conceived in vitro by the owners of Abercrombie & Fitch in 2000, who even invented a fake origin story to make it seem more “historic” and rooted in the imagery of Californian beaches. Hollister’s case perfectly demonstrates the strength the trend had in those years: to exploit the charm of surf culture and California vibes, a retail chain was willing to completely invent a founder and create store facades resembling Malibu homes.

The more historic surfwear brands, in any case, arrived in Italy “delayed” thanks to a series of licensing agreements, the most important of which were the acquisition of the Maui & Sons license for Italy by Maurizio Cocchi in 1986 and that of Scorpion Bay by the Mistri family in 1992, which became a full acquisition in 2007. The commercial licenses for Italy made these brands “new” for the country when they were already over a decade old. Needless to say, their arrival helped create the belated Italian mall brand culture that saw the rise of a number of flash-in-the-pan brands that became so connected to the world of teen/preteen youth of that era that they remain painfully outdated today. Yet those fashion brands, whether international or local, established a stylistic *koinè* within that vast multiverse that was the Italian province – a world that in the early 2000s (and to a lesser extent even now) was completely alien to the idea of fashion and trends, frozen in a conservative inertia that only the arrival of fast fashion giants like Zara and H&M and their entourage of fast fashion brands managed to shake, though not break. The teenagers of that time, who grew up with Transformers, Bionicle, Disney’s Gargoyles, anime like GTO, and cartoons like Street Shark found in the Hawaiian graphics of Maui & Sons and Scorpion Bay a breath of a world halfway between childhood fantasy of toys and cartoons and the more grown-up thrill of adventure and Californian surf imagery.

Looked at in retrospect, all these surfwear brands share something: the same visual language, the same emphasis on graphics decorating basic garments like t-shirts, sweatshirts, and swimwear, and the same obsession with the logo, repeated and varied in always different fonts. These were sporty garments but lacked the ambition and athletic aspiration of more traditional sportswear brands. They had little to do with the technicalities of “real” surf gear and were mainly sold to an audience of teenagers, like the Italian ones, who were relatively unfamiliar with surf culture. In other words, these 2000s surfwear brands were selling a certain type of fantasy or, as Hampton Carney of Abercrombie & Fitch put it: "It’s more about the lifestyle and the inspiration than the actual activity." This mechanism of lifestyle inspiration was already present in fashion, but in recent years it’s been taken to a new level: from Casablanca and Miu Miu eyeing the world of tennis, to Hedi Slimane’s perennial fascination with motorcyclists, their stunts, and their leather jackets; from Gucci reinterpreting running aesthetics with Adidas and reimagining equestrian accessories, to Jacquemus turning scuba gear into it bags.

Still, whether fashion or streetwear, there hasn’t been a unifying trend or lifestyle inspiration since those years that shaped an entire brand and became a clearly observable and lasting “phenomenon” like the rise of surf brands in the early 2000s. In a post-streetwear era, after the intoxication of graphics and branding that led many middle-range brands to lose their drive to cultivate a truly unique personality, becoming increasingly generic and broad in appeal, the case of those surfwear brands is an important lesson in the value of concept and pop aspiration, which doesn’t have to be synonymous with luxury. After all, for many Millennial kids, Californian-inspired surfwear brands were the first taste of a pop and aspirational fashion that, ten or twenty years later, in some cases, became real fashion.