The Indie Sleaze era had its ugly stuff too The revival of an era does not necessarily have to be a revival of its most cringe-worthy aspects

One of the most well-known yet most overlooked aspects of the human condition is people's ability to look at the past with far more lenient eyes than those with which they view the present. Memory, like a snowfall, covers every scene in poetry, hiding the prosaic, the unpleasant, and even the ugly. This is what we are witnessing today with the return of the Indie Sleaze world which, after an initial revival several years ago, now seems to have become a permanent installation in our hyper-fragmented contemporary pop culture.

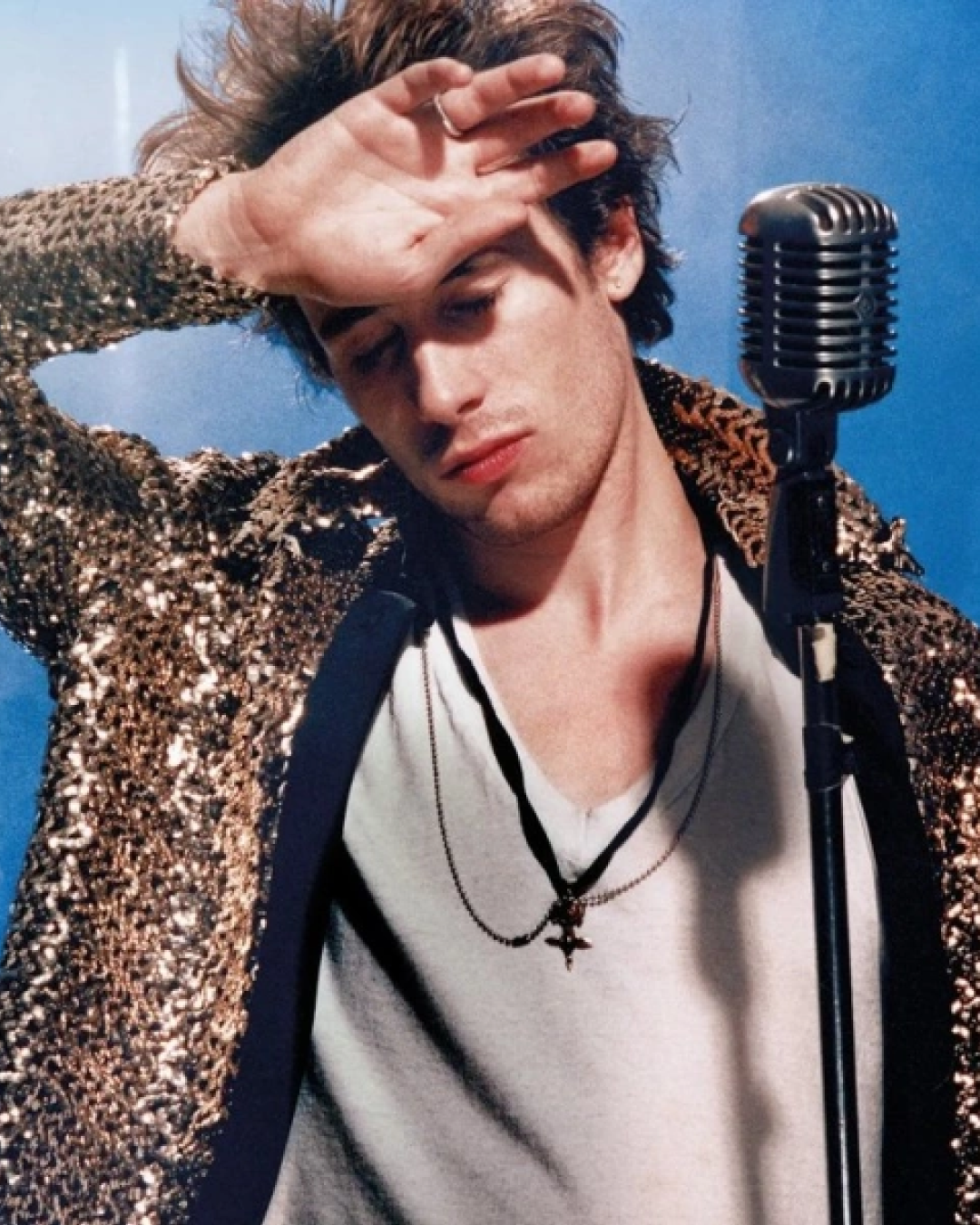

There is only one problem. For those who, like the person writing these words, remember that era because they lived it, Indie Sleaze is not the cool, artfully crafted aesthetic seen on TikTok today—far from it. To put it bluntly, one could almost argue that the current Indie Sleaze trend is nothing more than a form of cultural revisionism in which very different phenomena and fashions that coexisted in those years are lumped together under a single umbrella. In other words, there is a tendency to merge the world of indie rock (that of Pete Doherty and The Strokes) with that of the hipsters (think The Lumineers and “clap stomp music”), while also mixing in Tumblr culture and the trashy Y2K aesthetic of Paris Hilton and Jersey Shore, known as Nu Bling.

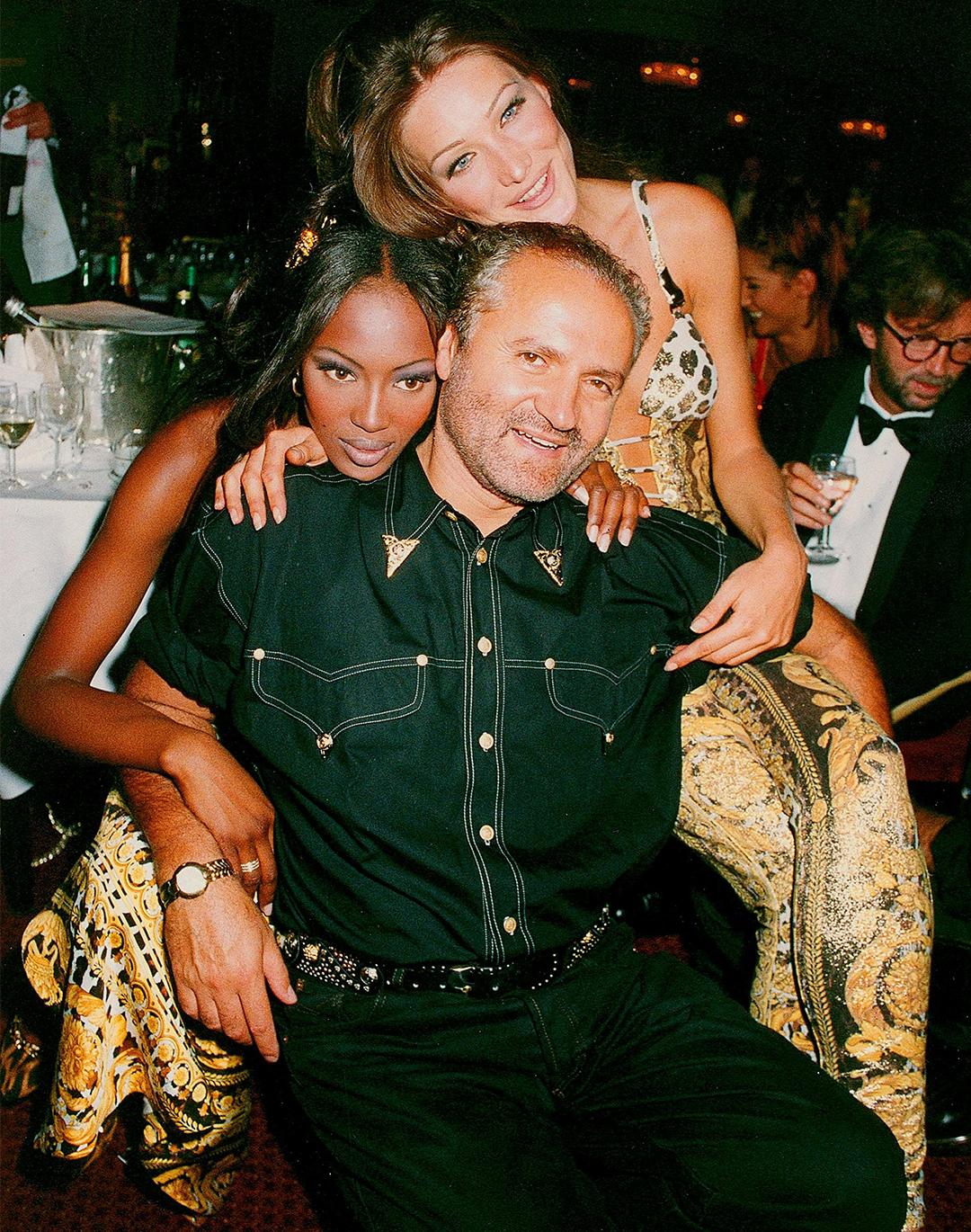

However, it was a well-delimited era of culture (as rough temporal markers, we could say it began with the 9/11 attacks and ended with the founding of Off-White in 2013), even if it is difficult to define and quite multifaceted. So, much like what happens with the 1980s, does it make sense to retrospectively unify it under a single nostalgic perspective? Yet, for the sake of fairness, we must also recall its aspects—not ugly, but at the very least cringe. What was the worst of the Indie Sleaze era?

Were we really that well-dressed?

The silhouette of the era found its fullest expression in Hedi Slimane’s collections for Dior and Christophe Decarnin’s for Balmain. It was the exact opposite of today’s dominant one: instead of fitted on top and loose at the bottom, it preferred tight legs and oversized tops. In many cases, the top tended to fall like a tunic over legs clad in jeans or even just tights, which back then were worn under denim shorts. In high fashion, style was certainly not lacking, but in the world of ordinary mortals, the trend created quite a few distortions: low-rise skinny jeans, popped collars featuring inner graphics, leggings in every color, long tank tops with sadly ironic slogans.

The most infamous garment of the era is undoubtedly the American Apparel Disco Pants, i.e., shiny spandex leggings that in the US became so notorious they earned their own Wikipedia page. But perhaps the most globally hated signature item was the wide-brimmed hats popularized by bohemian icons like Pete Doherty and Johnny Depp, which then quickly invaded the wardrobes of young Millennials with quirky bowlers, porkpie hats, and horrible fedoras like those worn by Justin Timberlake and Ne-Yo at the time.

omg are we going back to sexy business casual for the club?! lol pic.twitter.com/0WrsKIdzN2

— Taesty (@BrownSugarTae) November 18, 2025

Another terrible aesthetic plague was the so-called “business casual” look, which for years made the best outfit for going dancing a blazer with a top full of ruffles, a giant belt in a clashing color, skinny jeans, and heels. The business casual craze, which toward the end of the period veered into western/19th-century territories, also led to the spread of oxfords or brogues, i.e., laced leather shoes with a cap toe. To top it all off, there could be no shortage of gigantic glasses in obvious contrast to the side-swept fringe hairstyles à-la-Justin Bieber, which were often worn without lenses.

The tendency to decorate everything all the time then led to the flourishing of costume jewelry (back then stores like Accessorize were hotspots of the culture), with hipster-themed trinkets like the famous owl pendant, and above all brought an excessive quantity of bracelets of every kind to the wrists of men and women alike, turning them into a sort of diary of the wearer’s life: plastic beads, rubber bands, steel ID bracelets, festival wristbands, and nightclub passes.

The call of the exotic

this comes from the early 2000s. It was used for a specific kind of tribal tattoo popular at the time. The term was derogatory as tattoos in western countries had not yet become widely accepted in the eyes of the public pic.twitter.com/1PrCizwf7m

— Max Aveniedas (@KnightmareAlpha) August 31, 2022

In the very early 2000s, one of the coolest things around were the famous “tribal” designs originally invented by tattoo artist Leo Zulueta in the late ’80s at the legendary Spiral Tattoo studio in Los Angeles. After an initial spread in the ’90s, they crashed into mainstream culture the way Labubu dolls crashed into ours just last year. From Ed Hardy shirts to David Beckham’s tattoos, from pseudo-Hawaiian shirts decorated with stylized dragons to sticker-like tattoos found in chip bags, those motifs were everywhere. Today we would call it a case of cultural appropriation, as those tattoos were heavily borrowed from Samoan culture and South Pacific peoples in general.

@90sbaby2000s_teen Did you own one? I remember wearing a Magenta one with a SpongeBob tee in like 2007… #keffiyehscarf #keffiyeh #2007 #2007trend #2000strends #2000sfashion #petewentz #falloutboy #scenefashion #hipsterfashion #2000steen #2000steenager #heytheredelilah #emoscene #emoscenegirl original sound - Jacoby

Then there was the keffiyeh which, after the anti-Islamic panic spread by 9/11 and the start of the Iraq War, became in the West a generic symbol of rebellion against the system—similar to the Che Guevara t-shirt—and was sold both by avant-garde fashion brands like Raf Simons (who included one in his famous FW01) and Balenciaga (who made it for FW07), as well as by stores like Topshop and Urban Outfitters or the emerging Zara and H&M at the time.

@sarahhiraki It's more problematic orientalist fashion from the likes of Seventeen Magazine and Delia's! Did you own any of these? It's time to look back, cringe, and do better in this decade. #stopasianhate #orientalism #y2kfashion #90sfashion #japonisme #chinoserie #fashionhistory #learnontiktok Lofi nostalgic old music box(833007) - NARU

Nor can we avoid mentioning the collective and superficial fascination with Asian culture, particularly Japanese and Chinese, which ranged from writings on clothes to the entire Pucca franchise (though it came from South Korea) to the qipao trend, i.e., the Chinese dress with an asymmetrical neckline often completed with two chopsticks in the hair. A symbol of this sort of neo-Orientalism is the art direction of Gwen Stefani’s videos with the Harajuku Girls or the famous Karlie Kloss geisha shoot in Vogue.

A strange color theory

Finally, amid tight and elongated proportions, platform heels, zip-up hoodies paired with shirts and ripped jeans, what reigned was a completely disharmonious color theory, to say the least deliberately chaotic. There was a strong emphasis on a “mismatched” mix that gave the impression of having grabbed pieces at random from two or three different wardrobes. The dominant base was certainly black, almost omnipresent on skinny jeans, leather jackets, hoodies, and blazers. Second to black came optical white, blinding and synthetic, heavily used for the famous shutter shades but also for the black shirt + white tie combination that claimed so many victims over the years.

On these bases were piled plenty of metallic and shiny accents, from studs to lamé fabrics; acid green, shocking pink, orange, or electric blue garments, especially on t-shirts, scarves, and socks. There was a year when purple and eggplant were huge. A touch of bright red was much loved for shoes, bags, belts, and in the worst cases even pants, mixed together with very flashy and invasive graphics as well as animalier prints. Even pastels and neutrals were vaguely “dirty.” An entire style that aimed to evoke not so much real raves as parties very similar to those in the film Project X, which arrived, in fact, right at the tail end.