The new role of fashion archive curators and researchers explained Between ethics, technical expertise and creative activation, how conservation rethinks the future of clothing

In the fashion industry and beyond, one could say that archives are genuine relics. Some consider them untouchable, while others believe they serve to rewrite history — as when Kim Kardashian sparked heated debate by wearing (and damaging) a dress that once belonged to Marilyn Monroe at the 2022 Met Gala. While both perspectives present valid arguments, one thing is certain: fashion archive pieces are not a frozen museum, but a living library and a driver of reinvention for the future. It is from this conviction that The Red Mannequin, the research and storytelling laboratory founded by stylist Alessandro Ferrari, was born.

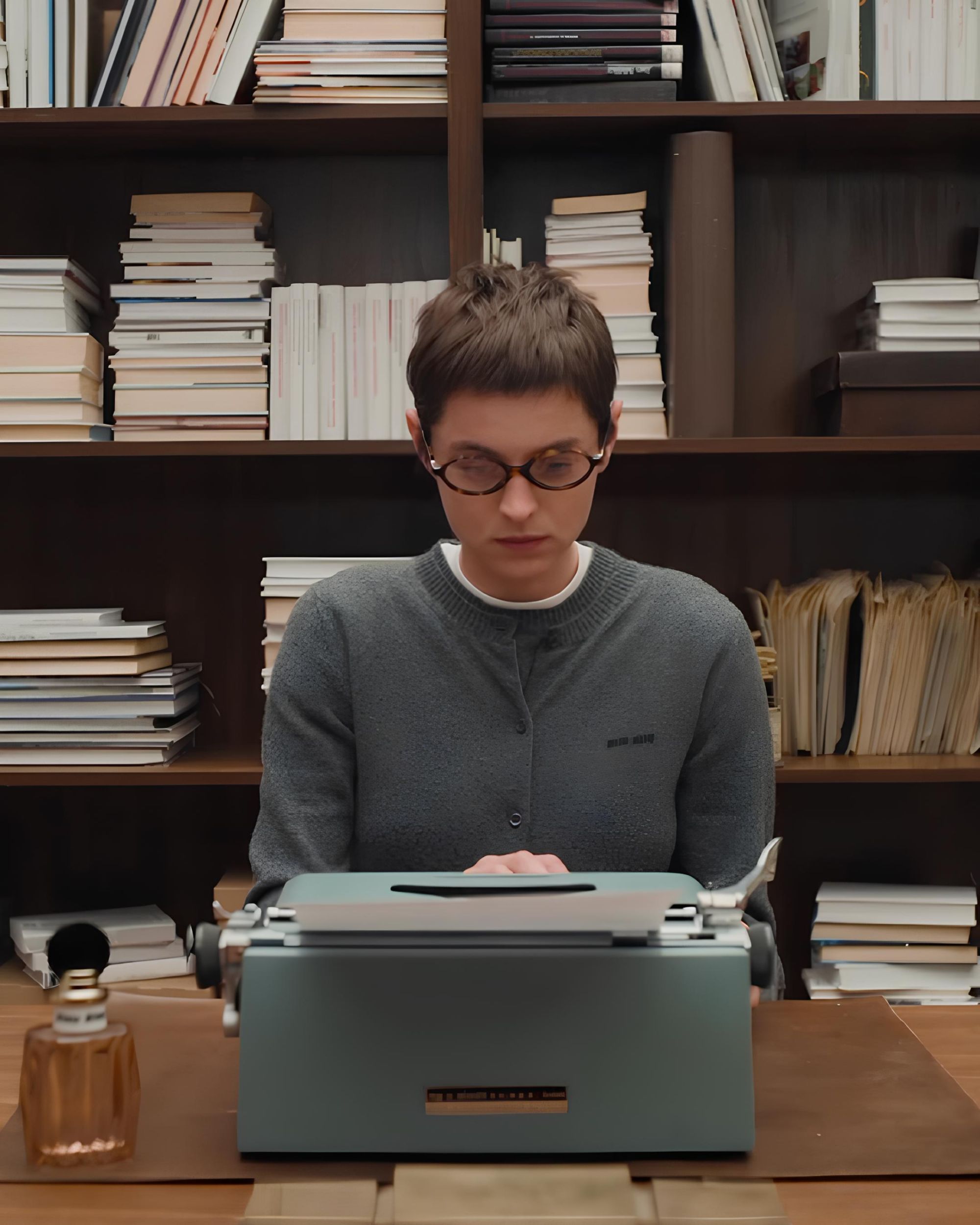

For the stylist and art director, the archive is an endless quest, fueled by a desire to rediscover fashion as a field of experimentation rather than mere consumption. "To find archivale pieces, I look everywhere—dealers, old stock, vintage and flea markets, even unexpected places. In general I love thrifting and research, it’s part of my work as well as a freelance Fashion Stylist. What matters is the eye."

Behind the excitement of discovery lies a technical rigor and sharp intuition, as Alessandro explains. Determining the value of a piece is not only a matter of brand or date — one must also understand its construction, labels, fabrics, and situate it within a designer’s chronology. “Dating a piece is technical work, but over time it has become intuitive: you eventually learn to grasp the value of a garment immediately. I do a lot of research on past runways to see whether I can find the exact piece that attracts me, or something similar.” Even forgotten pieces, those lacking labels or from little-known eras, carry lessons — fragments of the history of materials and methods: “Sometimes the brand or date matters little in my research: vintage pieces use different fabrics and materials, and I simply find them interesting. We can learn something from each one.”

The ethics of responsibility and the garment’s life cycle

Private archives carry within them a certain ethics of responsibility, a constant balance between activating pieces and preserving them. Unlike today's fashion, where speed dominates, archival garments demand a form of reverence. “If a piece must be handled carefully, we use it with precision — controlled fittings, minimal tension, always with respect. This is absolutely essential with an archive: each piece feels alive and requires care because it is irreplaceable.” Yet respect often clashes with the reality of rentals and usage: “This is sometimes the hardest part when renting, because not everyone pays the same attention or care to these garments.”

But the greatest threat is not the fragility of fabric nor those who borrow it — it is the risk of making the piece inaccessible. “The main ethical challenge in private conservation is responsibility. A private archive offers freedom, but that freedom has limits. You can activate pieces, but you must know when to stop. The challenge is to protect the garment without turning it into something inaccessible or purely decorative.”

The archive as a direct bridge between two eras

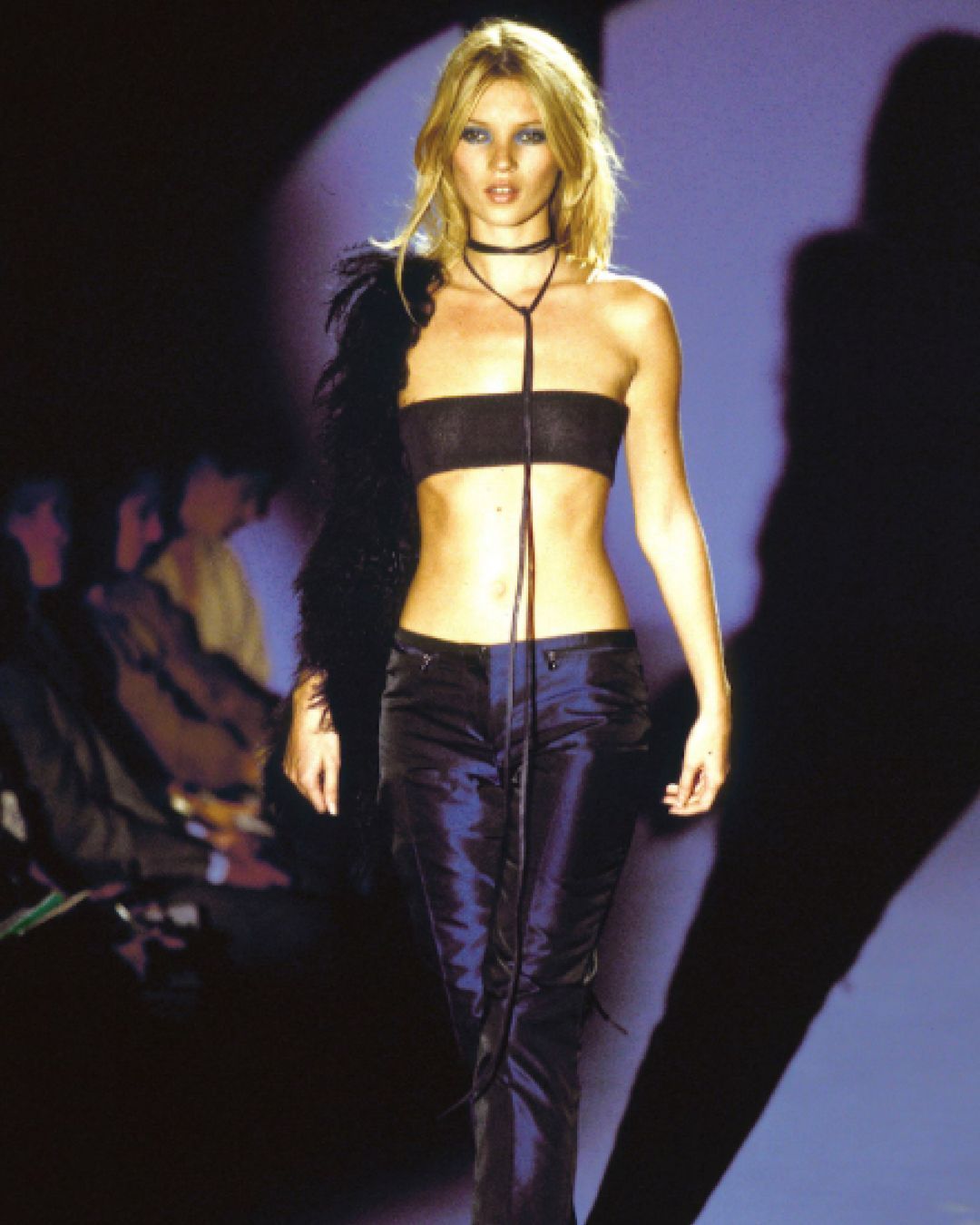

In a world where fast fashion reigns supreme and the industry produces roughly 800 collections a year — from haute couture to ready-to-wear, from Milan to Paris to London and New York — archives and their preservation provide a language fast production has often forgotten: that of slowness, intention, and physical craftsmanship. “Today, private collectors are here to help connect past and present. Not in a nostalgic way, but in a practical one. Designers, stylists, and creatives refer to archives to understand construction, proportions, and ideas that no longer exist in fast production cycles,” Alessandro explains.

A collector becomes a reference point, not a gatekeeper. This wealth of material helps restore justice to silenced voices — bold designers from the 80s and 90s whose radical experimentation never reached the dominant narrative. “Archives can bring these creators’ voices back without rewriting history — simply by showing the clothes.” Even 3D digitization, though it is the future of preservation, will never replace the physical experience, Alessandro continues: “It will be a major tool, but it will not replace physical archives. Fashion is material — weight, movement, imperfections. 3D can document these elements but not replace them. It expands the archivist’s work rather than threatening it.”

The Red Mannequin: an active symbol

The name The Red Mannequin began as an aesthetic nod but evolved into a symbolic manifesto. Red, Alessandro’s favorite color, embodies power, emotion, and bold beginnings. “The name ‘red mannequin’ started as an aesthetic choice, but it also carries a symbolic meaning: red is important to me, as it’s my favorite color and represents power and emotion. It’s the opposite of neutrality, and archives are not neutral. They are active spaces.” The mannequin itself is a neutral form, a blank page upon which anything can be imagined. This evolving platform, which includes biannual exhibitions and collaborations, is above all an invitation to expression. As Ferrari states: “The real work of a stylist is to reinvent. To take something familiar and make people see it differently. That is exactly what The Red Mannequin is about.”