The business of lost luggage auctions Is this the new frontier of secondhand?

Perhaps the second-hand craze has truly reached its limit. After years spent moving between Vinted, Vestiaire Collective, Depop, and Catawiki, the online conversation has gone beyond the official resale channels, venturing into increasingly unlikely territories: first, the goods confiscated from the mafia, then the court second-hand shops, and now the lost luggage from airlines. It is precisely this latest frontier that has captured the attention of the internet, turning the idea of shopping into an experience that goes far beyond conscious consumption and literally opening up a debate on the boundaries of privacy. In the United Kingdom, for example, London Heathrow Airport auctions off luggage that, after months of storage and failed identification, remains unclaimed. According to an investigation by the Guardian, the journey of a lost suitcase is long and often unpredictable: in 92% of cases, it is returned to its owner, but when the tags come off or the documents inside are not enough to trace the traveler, the suitcase ends up in third-party hands. That’s where a private object becomes a public commodity, opening up a market that oscillates between the allure of mystery and the unease of rummaging through someone else’s personal belongings. And above all, it feeds the now voyeuristic inclination of TikTok.

@beckysbazaar Replying to @hannahhuskinson5342 PART 2!! The most random selection of things were in this suitcase from @undelivrd Do you think it was worth £129? #lostluggage #suitcase #unclaimed #unclaimedmail #airport #thrifted #unboxingvideo #mystery #mysterybox original sound - Becky’s Bazaar

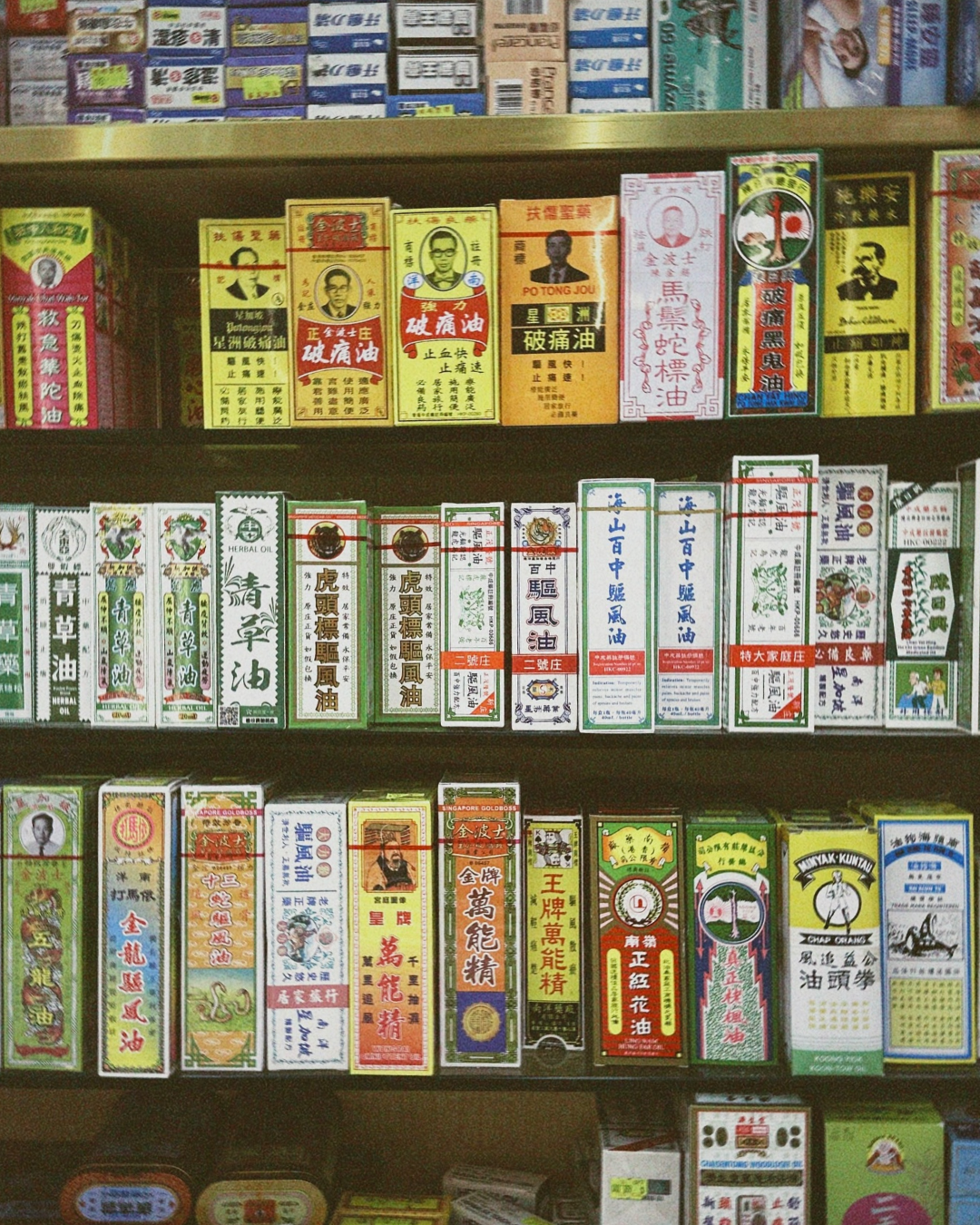

It was the creators themselves who turned this practice from a niche curiosity into a viral trend. Becky Chorlton, better known as @beckysbazaar, bought a lost suitcase for about £80 and, once opened in front of her community, found herself with an improbable assortment: from a pair of new UGGs to a locked iPad, along with clothes, makeup, and all kinds of accessories. The video gathered almost half a million likes, a sign of how much audiences are drawn to the idea of witnessing a kind of “unboxing of intimacy.” The account @ink.couple1, after purchasing three different suitcases at auction, revealed in one of them a surprising selection of designer pieces by Fendi and Palm Angels. Same dynamic for Carmie Sellitto, who in front of 1.2 million followers unwrapped a purple suitcase from Heathrow, finding not only crumpled clothes but also a Cartier box with the receipt for a ring worth over two thousand euros and a vintage Louis Vuitton bag complete with personal documents. In that case, the story took an almost cinematic turn: Sellitto managed to track down the owner and return everything. But not all endings are so fortunate, as shown by the experience of creator @luciasland, who, after spending £13,0 ended up with an anonymous trolley that had belonged to a young girl, apparently Chinese, which contained nothing but clothes, books, and a pack of Pikachu sanitary pads.

wtf do you mean ppl can buy your lost luggage? bro what https://t.co/u64ZNV1sGn

— kemi marie (@kemimarie) May 10, 2024

And yet, while millions of users keep watching and sharing these videos, just as many find them deeply unsettling. In the comments, reactions of rejection are common, such as “buying someone else’s suitcase just doesn’t feel right to me”, wrote one user, while another asked almost incredulously, “why would you ever buy lost luggage?”. It’s not only a moral issue, but also the widespread feeling that this type of entertainment has crossed an invisible threshold, turning fundamentally personal, ephemeral objects, like crumpled clothes, documents, and the daily traces of someone else’s life, into spectacle material. The effect is a short-circuit between curiosity and discomfort: on one hand, the thrill of mystery, the chance of stumbling upon a hidden treasure; on the other, the awareness that behind every suitcase there is a real person, perhaps still waiting to get back what they lost. It is precisely this paradox that makes the phenomenon so controversial and, at the same time, irresistible. We now live in an era where shopping is no longer just an act of consumption, but an experience that must surprise, shock, and capture attention in a digital ecosystem where the ordinary is no longer enough. If in the past it was the discounted price or the archival desire that drove the second-hand market, today it is the voyeuristic dimension that has become the real added value. Looking inside a stranger’s suitcase doesn’t just mean buying a second-hand item, but entering the intimacy of a private life, turned into entertainment for millions of views, almost like a reversed “what’s in my bag”.