Why doesn't Italy know how to talk independent fashion? The case of D.A.T.E. and the paradox of success outside fashion weeks

Last Monday in Florence, the 20th anniversary of D.A.T.E. was celebrated, a brand founded in 2005 by four friends that has now become a significant presence in Italy and beyond, with €20 million in revenue and distribution in 950 points of sale worldwide and three flagship stores in Italy. Despite impressive figures and a production rooted in the heart of Tuscany’s footwear district, the narrative surrounding D.A.T.E. is still that of a “small” or “emerging” brand, a convenient but misleading label often applied to well-structured brands simply because they don’t orbit around Milan’s high fashion or fast fashion scenes with globalized strategies. D.A.T.E. does not seem to enjoy the recognition that other, less solid brands receive in the fashion system, a typical problem in our country where you can remain "emerging" for half a century. Twenty years after its founding, D.A.T.E. continues to grow, but outside the spotlight of the institutional fashion system, a system that today is in deep crisis. Why, despite artisanal quality, production traceability, and an evidently successful stylistic proposal, do this and other independent brands remain on the margins of the mainstream Italian fashion conversation?

The D.A.T.E. case clearly highlights the gap between commercial success and cultural recognition, which is widening more and more within the fashion bubble, where it's very easy to have one without the other. Indeed, the "official" narratives of Italian fashion seem to favor only a few big names. It's a reflection of a system that struggles to recognize value unless it comes with a codified glamorous aura: official calendar runway shows, international celebrities, editorial endorsements, and the narrative of a “new phenomenon.” But D.A.T.E. (like many others) is not a phenomenon: it is a healthy, solid company, founded on clear values and a short supply chain, efficient and made in Italy. It is a company that chose to grow gradually, building its audience steadily rather than chasing fleeting trends and media hype. Paradoxically, it is often marginalized from the visual and cultural map of Italian fashion, which continues to search for the next “cover-worthy” emerging name, failing to acknowledge the slower, more structured forms of success.

This paradox affects many independent Italian brands that, despite their creativity, the appreciation of often international clients, solid revenues, and efficient production structures, remain virtually invisible to the radar of the fashion system. This was also echoed by the finalists of Camera Moda Fashion Trust 2025, who often find it easier to sell their creations (often even custom-made) to foreign and especially Asian audiences than in their own country, where the public is wary of anyone who isn't a major historic name. Italy is, in theory, the home of quality, craftsmanship, and design. But in practice, the national fashion system operates with a binary logic that on one side rewards only the great luxury dynasties, and on the other intermittently celebrates new names that “emerge” thanks to targeted marketing campaigns or external support such as entry into private funds, backing by major digital retailers, or acquisition by luxury groups. But these “external supports,” while essential, are yet another confirmation that one always needs a paternalistic benefactor to rise from a swamp where no one saves themselves alone, a bit like in Dickens novels, where the happy ending always came through the hero’s admission into the dominant social system.

Today, in Italian fashion, those in the middle are systematically excluded from the official narrative. And yet it is precisely that “middle” that sustains the entire Italian fashion industry: brands like D.A.T.E., Golden Goose, or Candiani represent the beating heart of Made in Italy but also the most vibrant part of a business system that in the '80s and '90s allowed young designers without huge budgets - like Dolce & Gabbana in their very first collections - to expand dramatically and build empires. Back to the present, companies that innovate, produce locally, provide jobs in the territory, and contribute concretely to the sector’s GDP do operate and grow, but they often don’t feel the need to participate in Milan Fashion Week as representatives of truly functioning business models. Just consider that Italy has over 50,000 SMEs active in fashion and textiles, contributing just under €60 billion in revenue to the entire supply chain in 2024, a figure that declined due to the crisis but is expected to recover in the coming months. And yet it is precisely these businesses that suffer most from the lack of systemic visibility.

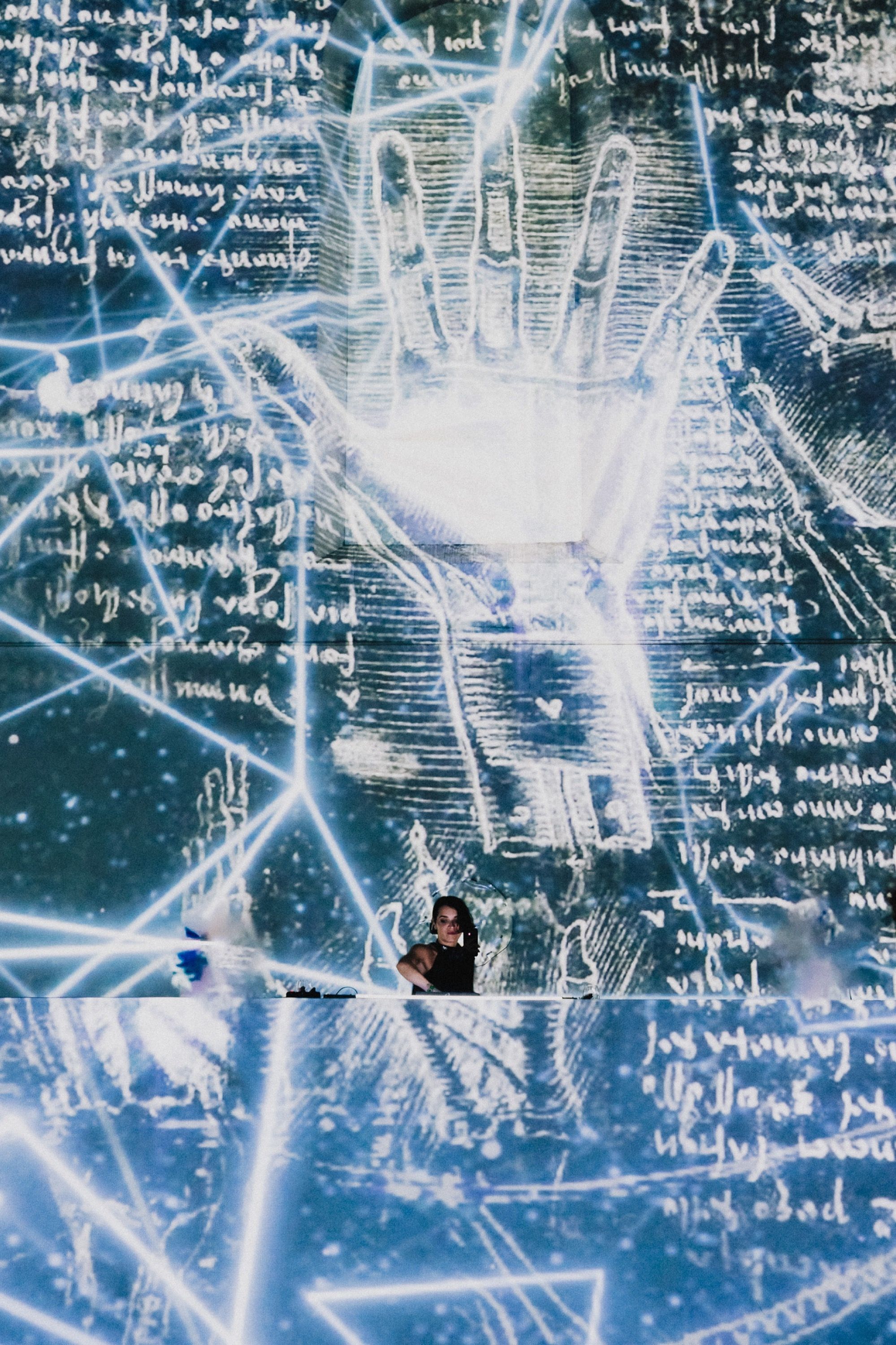

This distortion also has a strong cultural and media component. The Italian fashion system - from institutions to specialized media to communication and scouting platforms - feeds a narrative that tends to celebrate only the extremes: sacred monsters and social media meteors. In between lies a vast narrative void, inhabited by brands that are mature but not “iconic,” solid but not “legendary,” consistent but not “viral.” In an industry where appearance often matters more than substance, perceived success trumps real success. That’s why a brand like The Attico, despite being 49% owned by Moncler, is still perceived as an “independent” and “fresh” brand, while far more structured realities are labeled as emerging or, worse, ignored. It’s all a matter of narrative. And things don't improve when it comes to fashion week, whose show calendar is increasingly avoided by emerging designers looking to cut costs, and by major brands now opting for the faster co-ed format. Organizing a show in Milan costs on average between €40,000 and €150,000, and often the return in sales doesn’t justify the investment. Being on the official calendar doesn’t guarantee media visibility, unless there’s a strong PR office and a top-tier creative agency behind the scenes. That’s why brands like Act N°1, Vitelli, or Cormio, but also GR10K and Federico Cina, have chosen alternative solutions like presentations, digital events, or long-term storytelling. But this choice, often made out of necessity, is interpreted by the media as a sign of weakness, when in reality it reflects a structural and necessary change. Golden Goose, now a giant with €500 million in annual revenue and ten years of history, does organize its own extra-fashion events under the name HAUS of Dreamers, outside the framework of fashion week, where visibility is too often confused with value.

The real issue is that fashion in Italy lacks a system. Unlike what happens in France with la Fédération de la Haute Couture et de la Mode, or in the UK with the NEWGEN program by the British Fashion Council, there’s no structured and continuous mechanism to support new businesses. There is no national program to help independent brands face the challenges of transitioning from a start-up to a consolidated company, nor a public or private fund to facilitate access to credit for fashion businesses. And above all, there is no real mentorship system where established players support emerging ones, sharing resources, visibility, and know-how. CNMI has launched commendable initiatives such as the Fashion Trust Grant or the Designer for the Planet program, but without rethinking the system’s underlying mechanisms. Beyond the financial aspect, there seems to be a lack of a true culture of mutual support, and the dominant press - with few exceptions - tends to follow trends dictated by large groups or visibility algorithms. In Italy, there is a fashion industry capable of growing outside the system, with serious, coherent, well-crafted enterprises. But how much longer can it continue without proper recognition? Continuing to treat as “emerging” those with twenty years of history and millions in revenue feeds a distorted perspective that harms the entire sector. If we want Italian fashion to remain a cultural industry and not just a commercial one, we need a turning point. We need a system that acknowledges and values the plurality of success stories, that supports new brands even when they’re no longer “new,” that builds bridges between legacy players and new ones. Culturally, we also need bolder and more independent narratives that tell the real story, not just what sparkles. Because without this change, we will continue to miss stories like that of D.A.T.E.: stories of quality, vision, and resilience that deserve to be at the center, not on the margins.