In 2025 Gen Z is choosing debt over not traveling More and more under-30s are asking for loans to go on vacation

Where to go on vacation? The summer question is back, along with the pressure it brings. For many, the chance to spend time away from the city where they work all year is far from guaranteed. Economic difficulties intertwine with an uncertain geopolitical climate, and the consequences reach the very heart of the summer season. According to an investigation by Repubblica, this year about 9 million Italians will not go on vacation for financial reasons. But alongside those who give it up, a parallel phenomenon is growing—less talked about but increasingly evident: there are those who leave anyway, even at the cost of going into debt. In 2025, vacation seems to have become an inalienable right, defended even with microloan financial tools. In the first five months of the year, it's estimated that over 220 million euros in personal loans were issued to finance travel and holidays. The average amount requested is around 5,500 euros, to be repaid over a period of three or four years. What’s surprising is that almost a third of the requests come from people under 30: a generation raised with Ryanair and Airbnb, now squeezed between unstable wages and a cost of living that makes a weekend in Barcelona an expense to be spread over 36 convenient installments.

Is it worth going into debt because of FOMO?

dubai chocolate labubu matcha latte moonbeam ice cream crumbl cookie gen z stare jet2 holiday… i’m so tired pic.twitter.com/aGI1IicCVF

— ੈ (@wiIdfIowerrrr) July 13, 2025

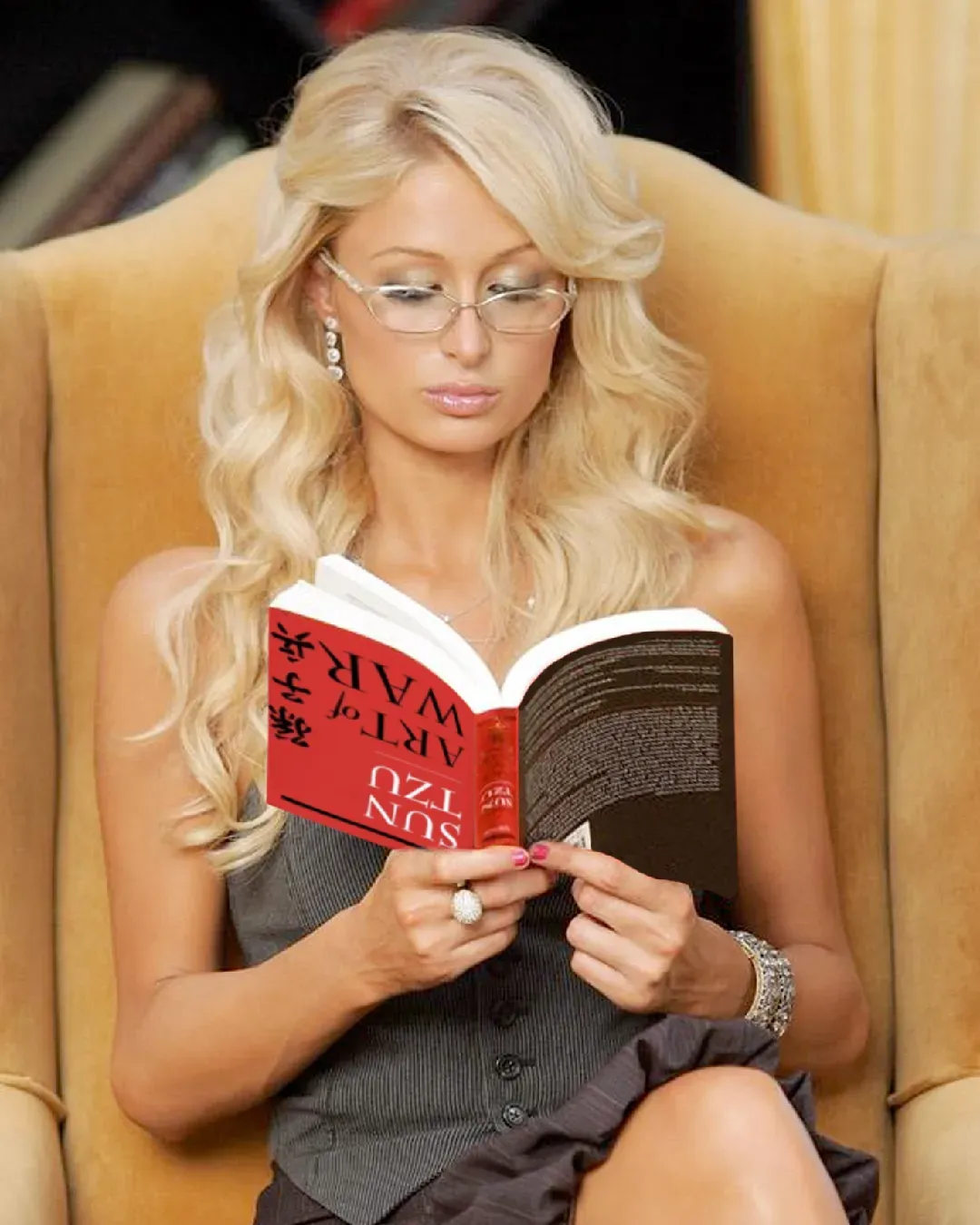

Behind the boom of credit-funded holidays lies not just the desire to escape, but a growing cultural pressure: the need to represent one's free time online, to perform vacation, to visually narrate one’s well-being. In an image-dominated climate, resting isn’t enough—vacation loses its primary function of recharging body and mind and becomes content to produce, an event to document. Relaxation and success go hand in hand, with perfectly curated feeds and captions. And those who can't afford it? They often rely on consumer credit due to FOMO, or fear of missing out on the collective narrative. The gap between real possibilities and performative expectations creates clear breakdowns. Free time becomes a moral obligation, while the idea takes hold that even rest must be quantified. Alternatives—small day trips, days at home with friends or family—seem insufficient unless shared, photographed, made public. And so, freedom bends to representation.

Yet there are still forms of pause that escape the rhetoric of the documented journey. Staying at home, reading a book with the shutters down and the surreal silence of an emptying city is not a defeat, but a therapeutic act, a mental space that escapes the logic of constant exposure, a suspended time that doesn’t need to be monetized. It’s not so much the vacation itself that has become necessary, but its representation. Borrowing a concept from Baudrillard, we no longer go on vacation to rest, but to prove we went. The simulacrum—the copy without an original—takes the place of the experience. And if it takes a microloan to get the perfect sunset, so be it. No one will post the overdrawn balance. Only the Negronis by the sea.