Are foley artists still a thing? History, success and comeback of a big screen craftsmanship

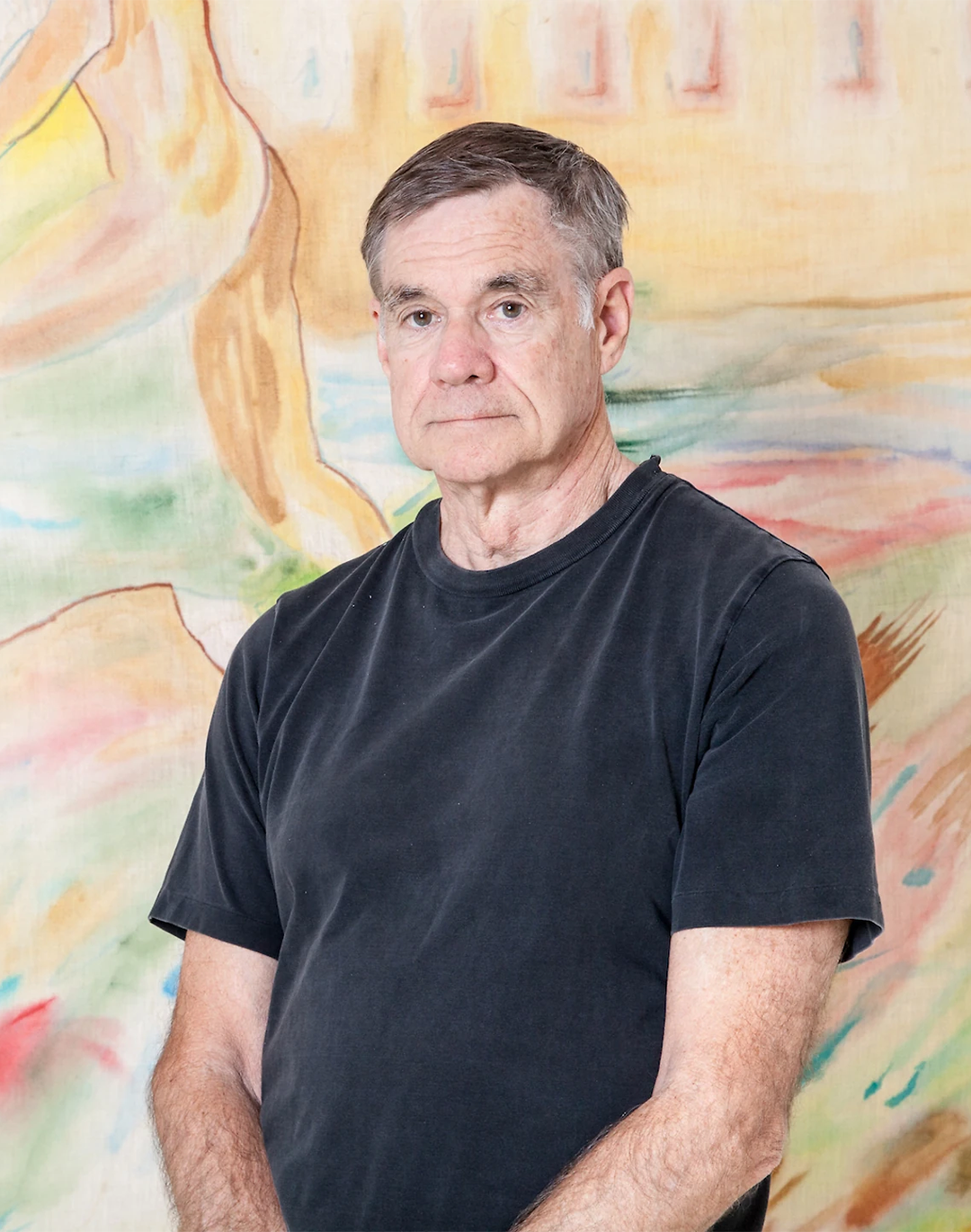

The first decision a foley artist must make at work is choosing the right shoe. The character’s walk, their presence in the world, the way they confidently or hesitantly move, whether they're going up or down stairs, whether their gait is decisive or uncertain. Whether it’s a man, a woman, walking on a street or gravel. It all comes down to the shoe. The professionals at Marinelli Sound Effects know this well, an institution in Italian film post-production with over fifty years of experience, founded before sound became all about digital libraries. In their studio, located in the heart of Rome’s San Giovanni neighborhood and hidden in plain sight behind the roundabout at Piazza Lodi, the history of Italian cinema has passed through, and for Marinelli Sound Effects, this meant giving life to some of the classics of our tradition. The story of Renato Marinelli, its founder, is a bit like something out of a movie: a projectionist at Cinecittà, from his booth as a young man, he watched a man arrive with a suitcase and, in front of a silent screen, pull out a whole series of unexpected tools. From iron plates to hair combs, to tubes or rubber bands. Like a magician, that man recreated the sounds that were only visible as images. In his free time, remembering the gestures of that wizard, Marinelli tried to imitate him. That’s how his career as a foley artist began, which led him to start a company and dominate the sound effects industry during the golden age of Italian cinema. Monicelli called him master, Fellini would often visit the Marinelli Sound Effects hallways, and Sergio Leone insisted that only Marinelli should handle the sound for his films.

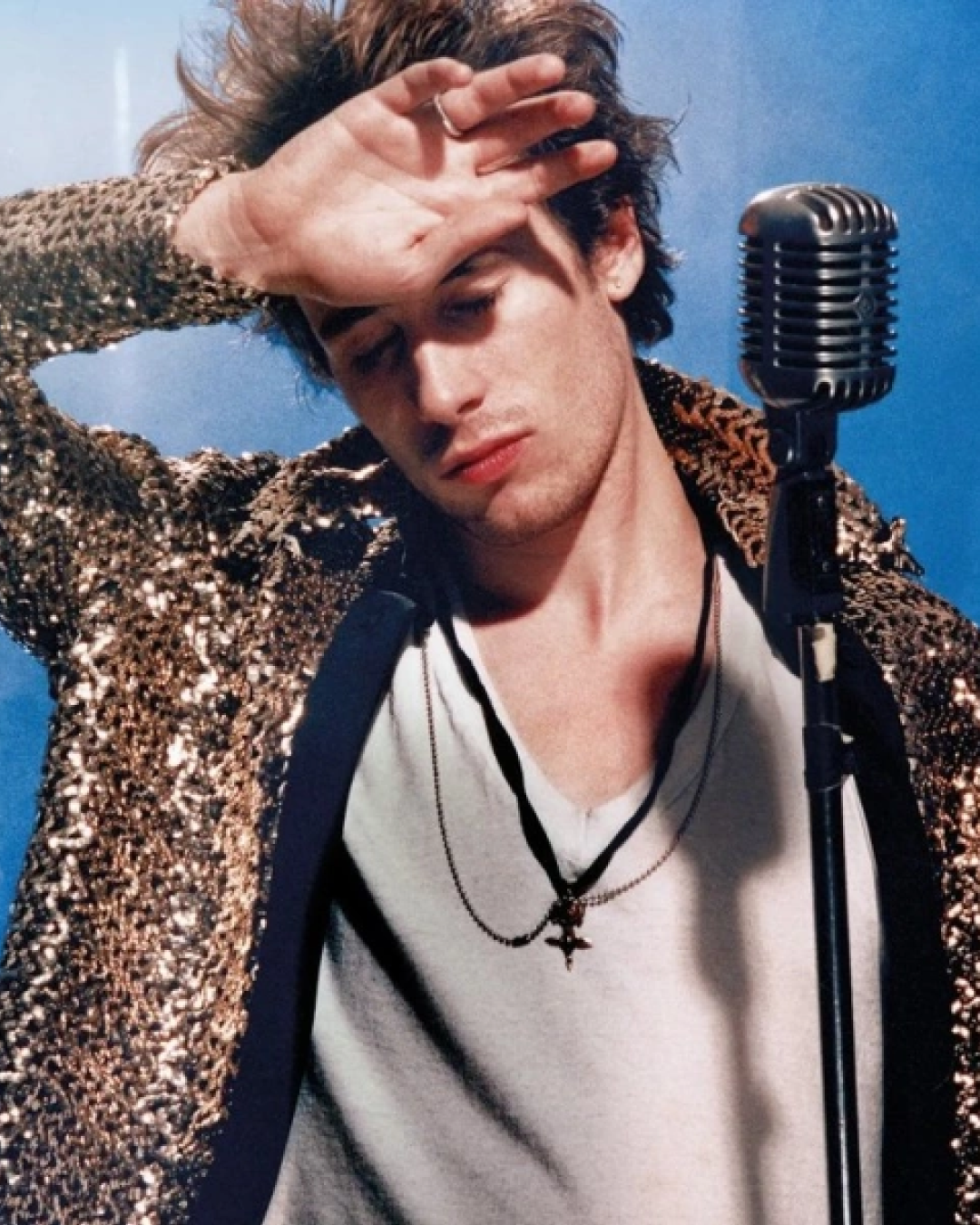

@joshplaysdrums Vintage Sound Effects! my take on this classic scene from Popeye, originally made in 1934! #rhythm #drums #food #sandwich #filmmaking #sounddesign #soundeffects original sound - Josh Harmon

Today, Marinelli’s studio is a true museum full of relics that represent a profession which, among many in the film industry, has changed dramatically with the rise and development of new technologies. Yet it’s thrilling to see how an entire drawer in one of the studio’s rooms is solely dedicated to all the different sounds that a 1960s Fiat could (or used to) make: starting, stopping, speeding on different asphalt types, or performing specific maneuvers. In modern times - like the mechanical age Charlie Chaplin tried to escape in 1936 - various effects can be found in specific digital libraries, but in the past, the foley artist would head out with their recorder to find them on their own. They always chased one thing first: the unexpected. Something they could capture which, through the magic that only cinema can recreate, could perfectly match the images on screen. Otherwise, they hunted for sounds they knew would be needed, like when Marinelli recorded his son Massimo’s eighteenth birthday party - Massimo, who now runs the company along with his daughter Giulia - and labeled it “teen crowd murmur” in case it was ever needed for a film scene with a crowd. Or that time when he and his team went out into a field for The Incredible Army of Brancaleone, simulating as many battles as possible with a wide variety of weapons, so they could faithfully recreate the film’s sonic backdrop, a seemingly crazy endeavor, much like the characters in Mario Monicelli’s film.

What must be clearly understood when thinking about a film’s sound is that, even though direct sound recording is highly valued today, there is always an artistic and creative component from the foley artist to complete it. Sometimes a sound is captured so well and so specifically during filming that it doesn’t need to be replaced. But most of the time, if a door, for example, is closed in a scene, someone must figure out how forcefully it was shut, what material it’s made of, what kind of house it’s in, and by going into that level of detail, the most appropriate sound for the film can be chosen. Then the sound mixing will integrate dialogue and reconstructed sound, creating an effect more real than reality. It’s a profession where the mechanical and digital aspects could take over, a risk Marinelli Sound Effects does not want to take. They preserve the playful, exploratory spirit of their founder, still keeping a crucial room in the studio where the foley artist on duty does everything they can to match real-life sounds. Even building their own tools - like sticks with sponges and plastic bits shaped like spider legs to recreate a dog’s footsteps (yes, the writer has seen such contraptions with their own eyes) - and bringing in all kinds of useful objects. A true Wunderkammer where the ordinary becomes endless possibilities, thanks to the sensitivity of a foley artist, a figure in whom years of practice meet a refined curiosity and listening ability. A talent invisible to the eye, but resonant to the ear.

@reelfoleysound Part 2: I walk walk walk them all! Love my job #reelfoleysound #foley #foleyartist #postproduction #lovemyjob #bts #audio #sound #foleyheels #foleyleaves #foleybarefoot #foleyfoley original sound - Reel Foley Sound -Foley Artist

One of the hopes of the Marinelli Sound Effects team is to make young filmmakers more aware of the crucial role of foley artists, as over the years, there has been a decline in interest in sound design during the early stages of a project. Although only in animation can a foley artist let their imagination run wild, the potential of using sound as an additional, stimulating, and creative element should not be underestimated, even in more conventional worlds. So much so that the M_SIDE Collective was born as an offshoot of the studio, offering its professionals and artists to work on project soundtracks, making the post-production process of a film, short, or documentary even more direct and complete - yes, even in documentaries, sound is partially recreated. Whether horror or fantasy, a work can have fun experimenting with sound, as told by Massimo Marinelli about the recent debut film The Rhine Gold by Lorenzo Pullega, where the director wanted the sound to be as carefully curated as every other element of the film, giving the movie an almost Fellini-like touch.

@thecinescope once upon a time in america (1984) #vertical #filmtok #film #movieedit #movietok #movie #cinematok #cinema #filmedit #robertdeniro watching the stars - Øneheart

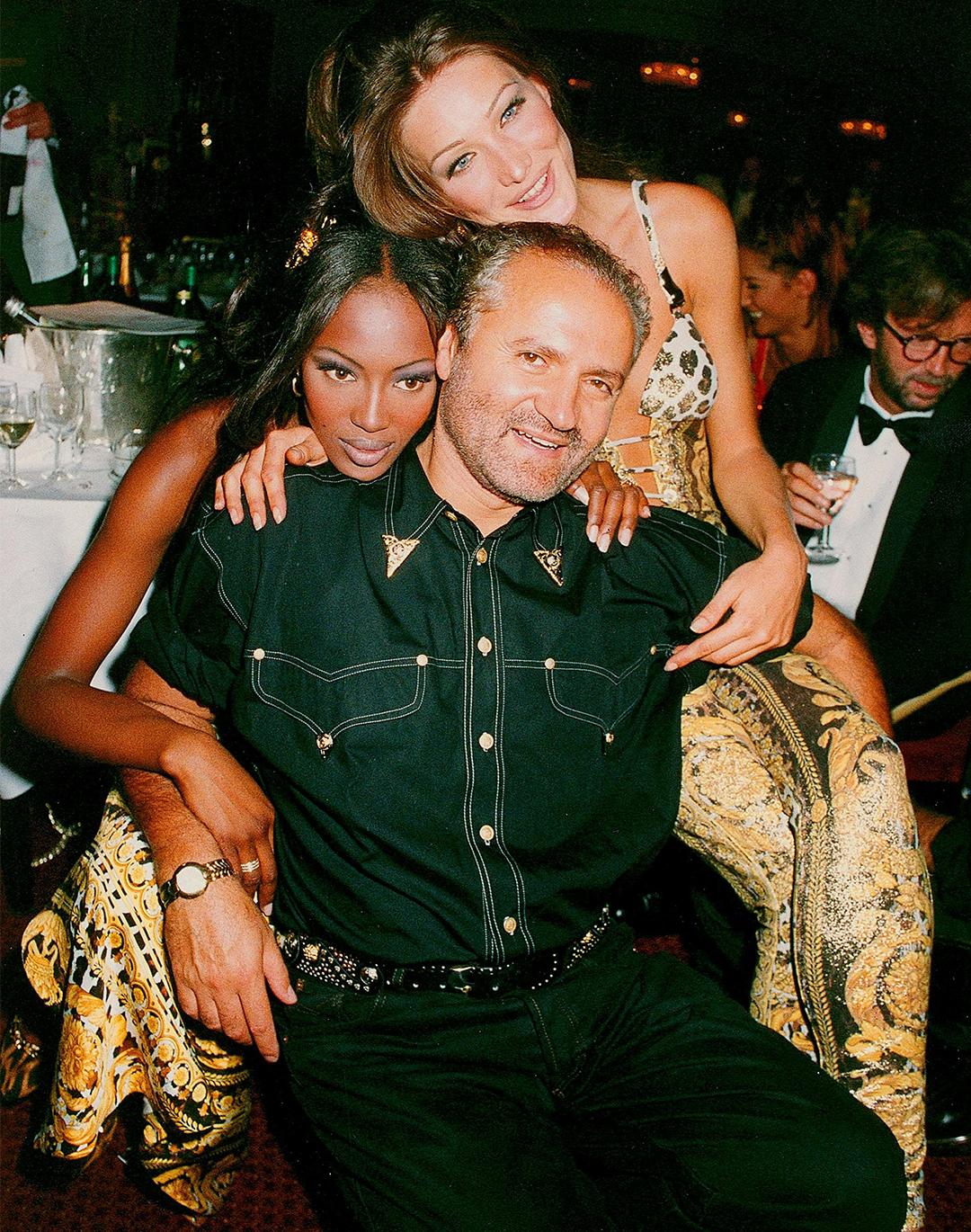

Although today it has become a fun game often recreated and shown as social media content, the videos by sound effects artist Josh Harmon are now famous, featuring even public figures like Post Malone and Jimmy Fallon - sound work has just as much narrative potential as visuals. It's also true that the film industry has now changed, with productions tightening budgets and timelines to finish projects as quickly as possible, a far cry from the six months Sergio Leone spent working on the sound for Once Upon a Time in America, compared to the two-week windows many professionals must deal with today. But as often happens with handmade work whose care and quality transcend time, going back to thinking of sound as an integral part, and not just a footnote, in the creation of a film could add wonder to a story and, why not, spark interest in a profession that often stays behind the scenes. Just think of how Renato Marinelli created the train explosion in Duck, You Sucker!: unsatisfied with the first results, Leone asked the foley artist to find a solution; causing chaos in the studio, aiming for maximum impact, Marinelli didn’t hesitate and toppled an entire cabinet full of as many objects as it could hold, items he had collected over time on his shelves (as only a true foley artist would). When Sergio Leone saw the result - which, for obvious reasons, had to be a one-take success - he asked Marinelli: «You didn’t actually blow up a train, did you?» He hadn’t. He had created something even more magical.