Che Guevara, the revolutionary that became merch The story of the communist icon favored by the fashion world

How does an icon survive? Sometimes, by transforming. Take the case of Ernesto "Che" Guevara, the legendary Argentine Marxist revolutionary, physician, author, and guerrilla leader who played a crucial role in the Cuban Revolution alongside Fidel Castro. His life's achievements were numerous, his impact enormous—but today, when we recognize his face on a t-shirt, could we explain the details of his life? Could we recount his motorcycle travels, the guerrilla warfare in Cuba, the U.S.-backed Batista regime, and his strategic genius in toppling it? Could we say that he served as Cuba's Minister of Industries, supported insurgencies in the Congo and Bolivia, and was ultimately captured and killed by CIA-backed Bolivian forces? Many would not know, and yet, his icon endures in pop culture (quite another thing is history) thanks to a single photograph.

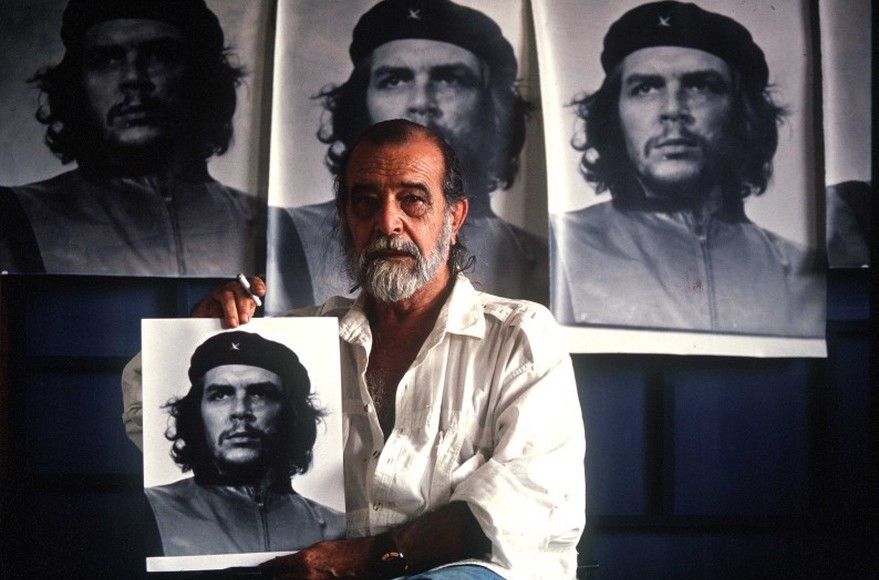

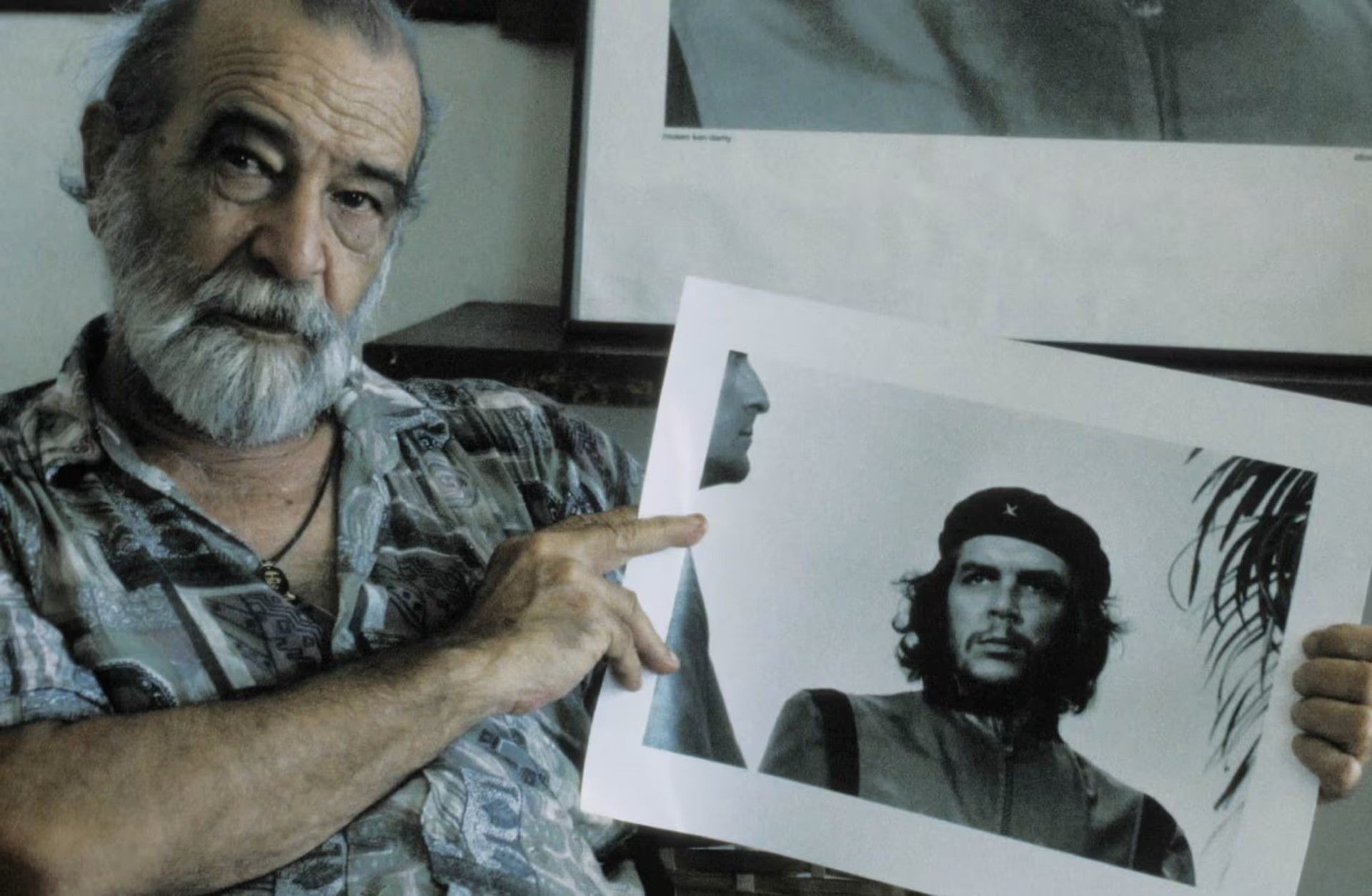

It was indeed the shot later titled Guerrillero Heroico by Alberto Korda, dating back to March 5, 1960, during a funeral in Havana for the victims of an explosion aboard a French ship, that became the visual pillar of his legacy. Snapped inadvertently during the ceremony (Guevara had entered the frame for just 10 seconds), Korda's portrait captured the 31-year-old revolutionary with a beret, beard, and intense gaze, against the most austerely honest black background imaginable. The photo was not published in Cuba due to its overly somber tone and was instead gifted by the photographer himself to Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir in 1961, who years later passed it to Paris Match where it appeared in 1967 amid reports of Guevara's Bolivian campaign and on the precipice of the youth movements that would shake Europe.

Martyr or Icon?

The commercialization of Guerrillero Heroico began almost immediately after Guevara's death, transforming a symbol of anti-capitalist fervor into a billion-dollar emblem of consumer culture. In 1968, Irish artist Jim Fitzpatrick, who had briefly met Guevara as a teenager, created a silkscreen poster version on a red background and distributed it for free at rock concerts and student rallies. Fitzpatrick's design became immensely popular, quickly reaching underground print shops in London and Paris, and by the end of the 1960s, it adorned walls during the 1968 Paris riots and U.S. anti-Vietnam protests.

In the 1970s and 1980s, the Guerrillero Heroico phenomenon continued to grow: bootleg t-shirts, posters, and pins proliferated at concerts by bands like the Grateful Dead and punk gigs, manifesting the first "detachment" between the photo and the ideology it represented. By 1969, U.S. printers like Print Mint in Berkeley mass-produced them for $2–$5, sold at rallies and head shops; sales skyrocketed during the 1970 Kent State shootings, symbolizing anti-war defiance. The 1970s brought detachment: with the end of Vietnam, Che t-shirts shifted from ideology to style, appearing in Andy Warhol's Factory scene and punk zines. Dutch anarchists printed variants in 1968, claiming Sartre's blessing, while a fake "Che" painting by Warhol (actually by Gerard Malanga, later "authenticated" by Warhol himself on condition that the money go to him) was sold in Rome.

By the 1990s, post-Cold War nostalgia and economic globalization transformed it into a design classic: Shepard Fairey's 1997 parody swapped Che's face for Andre the Giant's in the Obey Giant campaign, critiquing how icons become "empty signifiers." An interesting note is that Korda, a committed revolutionary, never registered ownership of the image, considering it public domain for the cause. The only time he sued someone was in 2000, when Smirnoff vodka used it portraying Che as a "revolutionary" partygoer. The lawsuit was won, and the proceeds went to Cuban hospitals.

Capitalizing on Anti-Capitalism

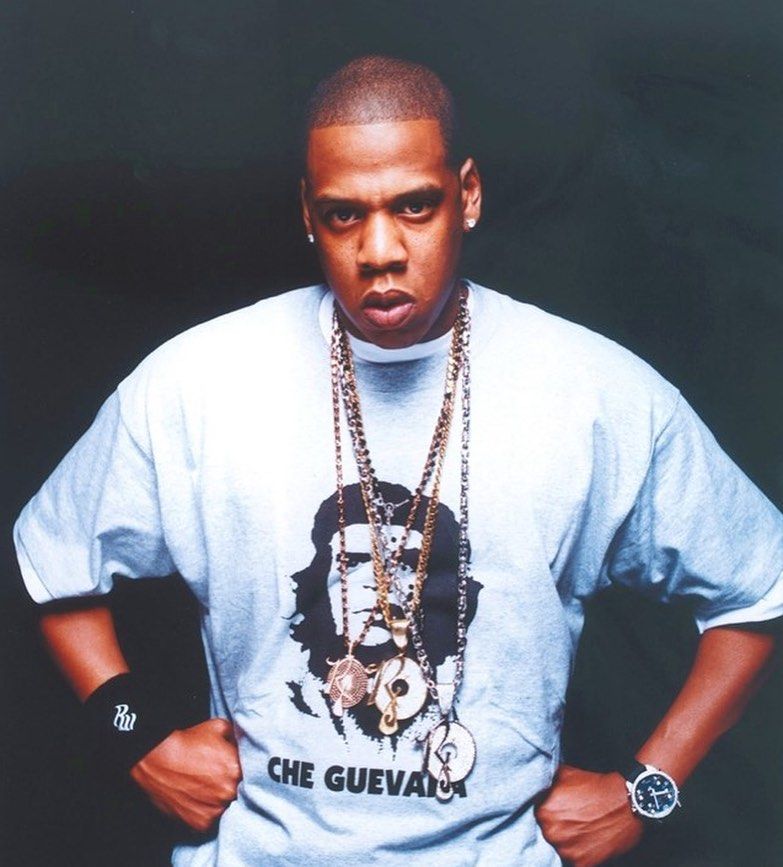

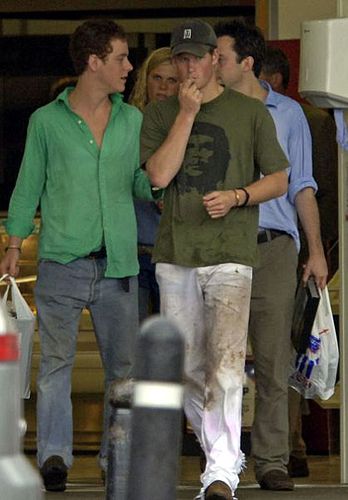

Already in the early 2000s, the irony of a communist icon transformed into a mass product was evident to all. The 2004 documentary Chevolution exposed this irony, estimating about 2 billion reproductions worldwide by 2008. Jay-Z referenced Che in his 2003 track Public Service Announcement ("I'm like Che Guevara with bling on"); Johnny Depp and Prince Harry sported them at events, while Bruce LaBruce's 2004 film The Raspberry Reich satirized them as "terrorist chic."

Once the heated moment passed in which Guevara's icon retained its original meaning, historical reinterpretations emerged, such as those by Cuban exiles who denounced Che's role in 55–105 executions at Havana's La Cabaña prison. Yet, as Aleida Guevara (Che's daughter) argued in a 2008 Guardian interview, the image's ubiquity fosters non-conformity, aligning with her father's dream of global equity. In the early 2000s, the Los Angeles boutique La La Ling printed Che on eco-sustainable onesies, the magazine The Onion created a satirical t-shirt in which the revolutionary wore his own portrait, while in 2008 the Scottish Tartan Army made charity t-shirts that placed poet Robert Burns in Che's pose, worn at Euro 2008 matches by over 5,000 supporters.

Even Obama's Hope poster was considered a copy of the Che photo. In 2012, it was Urban Outfitters' turn, which, despite being top sellers especially among youth, later withdrew them from the market after several protests. Today, with over 26,000 eBay listings for Che merchandise, it exemplifies capitalism's genius in co-opting dissent, selling the revolution back to the masses.

Che Guevara and Fashion

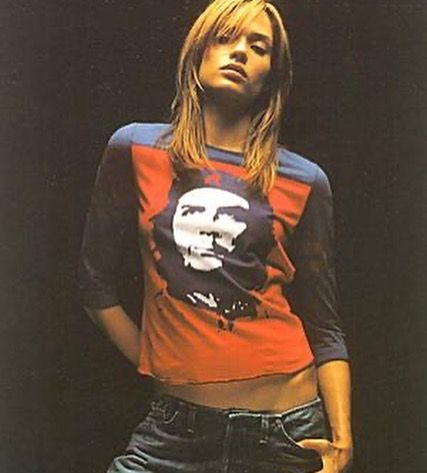

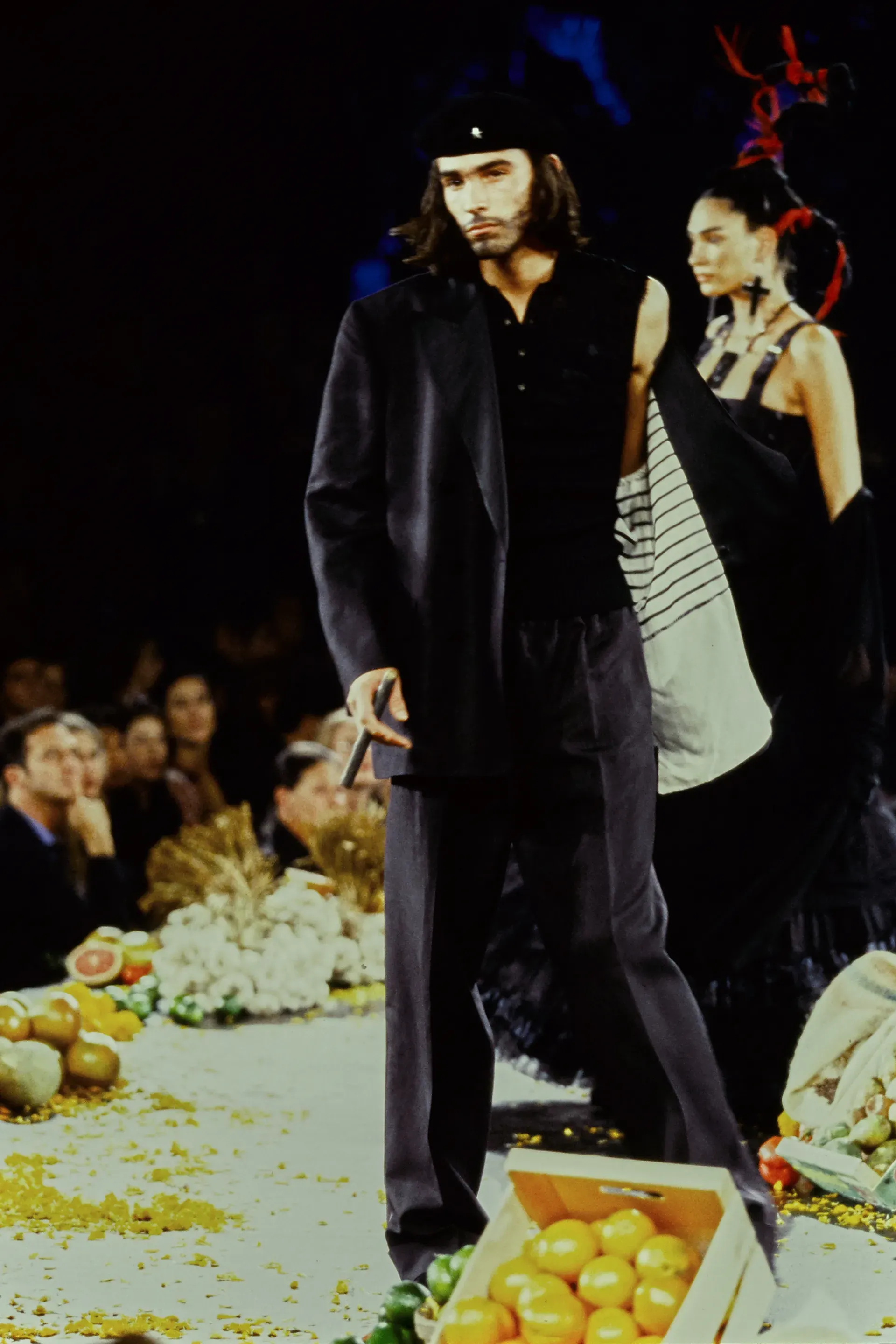

While the t-shirt democratized Che's image, luxury and streetwear brands elevated it to high fashion, often sparking periodic controversies. The very first was Jean Paul Gaultier in 1999 with a sunglasses campaign in which he surrealistically reimagined Che in a Fred Langlais drawing imitating murals, placing him next to Frida Kahlo. At Gaultier's SS98 show, then, one of the models wore a black beret and carried a cigar in a clear reference to Guevara. More frivolous but far more iconic was the Cia.Marítima brand, which in July 2002 at São Paulo Fashion Week opened with supermodel Gisele Bündchen wearing only a bikini covered in prints of Che's face.

Even more amusing was the case of Elizabeth Hurley, who in 2004 drew considerable attention when she was spotted dancing in London's China White nightclub, carrying a custom $4,500 Louis Vuitton Speedy embroidered with Che's features. An episode that unfortunately was not documented by any photos but whose memory survived in the press columns. In the same year, streetwear giants like Stüssy and Fuct commercialized t-shirts and hoodies printed with Che's face. In 2005, Belstaff immortalized Che in the "Trialmaster Che Guevara Replica Jacket"—a faithful replica of the olive-green model from Guevara's 1952 travels, detailed with epaulets and bellows pockets—while in 2006 it was Converse that printed the Guerrillero on Chuck Taylors, only to double down in 2010.

We returned to discussing Che Guevara several years later and for no small occasion: the historic Chanel Cruise 2017 show in May 2016. For the event, Karl Lagerfeld organized a $12 million spectacle in Havana with 600 guests and presented models in olive-colored jackets reminiscent of guerrilla uniforms and crystal-covered berets echoing Che's famous one, with the added interlocking C's of Chanel. A subversion of almost diabolical irony. Amid the U.S.-Cuba thaw, the show romanticized the revolution, but several Cuban-American exiles branded it as offensive glamorization of oppression, going so far as to protest outside Chanel stores. More recently, it was Supreme, in the SS21 collection, that unveiled a black nylon football jersey with an oversized Che print that sold out in minutes.

Today, so many years later, even if ideologies and divisions remain alive, and the anti-capitalist sentiment is more relevant than ever (take, for example, the online cult paid to figures like Luigi Mangione), we can calmly say that Che Guevara is a dated icon. Both because in the West we have decidedly lost the memory of the historical context in which he operated, and because what Che Guevara represented in the 1950s made sense in the general turmoil pre-1968. However, the premises of that protest have not retained their validity over time. Perhaps, for this reason, fashion could serenely do without Che: not disown him, but simply let him rest.