Whatever happened to fashion's desirability? By Antonio Dikele

At a time when the crisis of luxury and creativity is making fashion seem meaningless, consumers have once again started to crave something purely for the pleasure of having it, but also to resemble others who have it. What’s missing is a true object capable of polarising desire and popular culture, a magnet for attention and modernity. It’s in this context that micro-status symbols like Sonny Angels, Labubu, Hello Kitty keychains, and other colourful trinkets come into play: available at a much more affordable price than any designer keychain, yet still in demand and recognisable, these accessories represent the new frontier of hype culture, the missing link in a vicious cycle that began with Virgil Abloh’s collaborations and has led almost directly to today’s scenario: one of iconic products that are nearly comically inaccessible, and brands watching their stores empty of aspirational customers. The days when fashion attracted masses of young people by speaking to the protagonists of their culture seem far away, but the question of desirability as a driver of the fashion industry is nothing new: how many times, as kids, did we want to buy something just to look like our peers? How many times, as adults, have we believed that buying an entirely new wardrobe could give us another life, with more friends, more fun, less stress? We know that’s not how it works, and yet it’s precisely this feeling that trends continue to exploit: the desire to belong.

In this unpublished text, Italian writer Antonio Dikele explains, with a touch of healthy nostalgia, the power a clothing item can have over us. Or at least, the power it used to have. Because even though the world today is full of Labubu and Sonny Angels, of vintage and designer clothes adored by young creatives, with the death of hype culture, product desirability has also declined. As a result, brands find themselves chasing customers while reporting loss after loss in revenue. In 2025, the fashion industry seems to have forgotten that, while the world changes, consumer needs remain the same: to buy a product in order to belong to the community that wears it, to identify with a niche whose values they appreciate. It’s the product that creates desirability, not the image. That, as Dikele explains in the text below, comes afterward, shaped by the people who wear it.

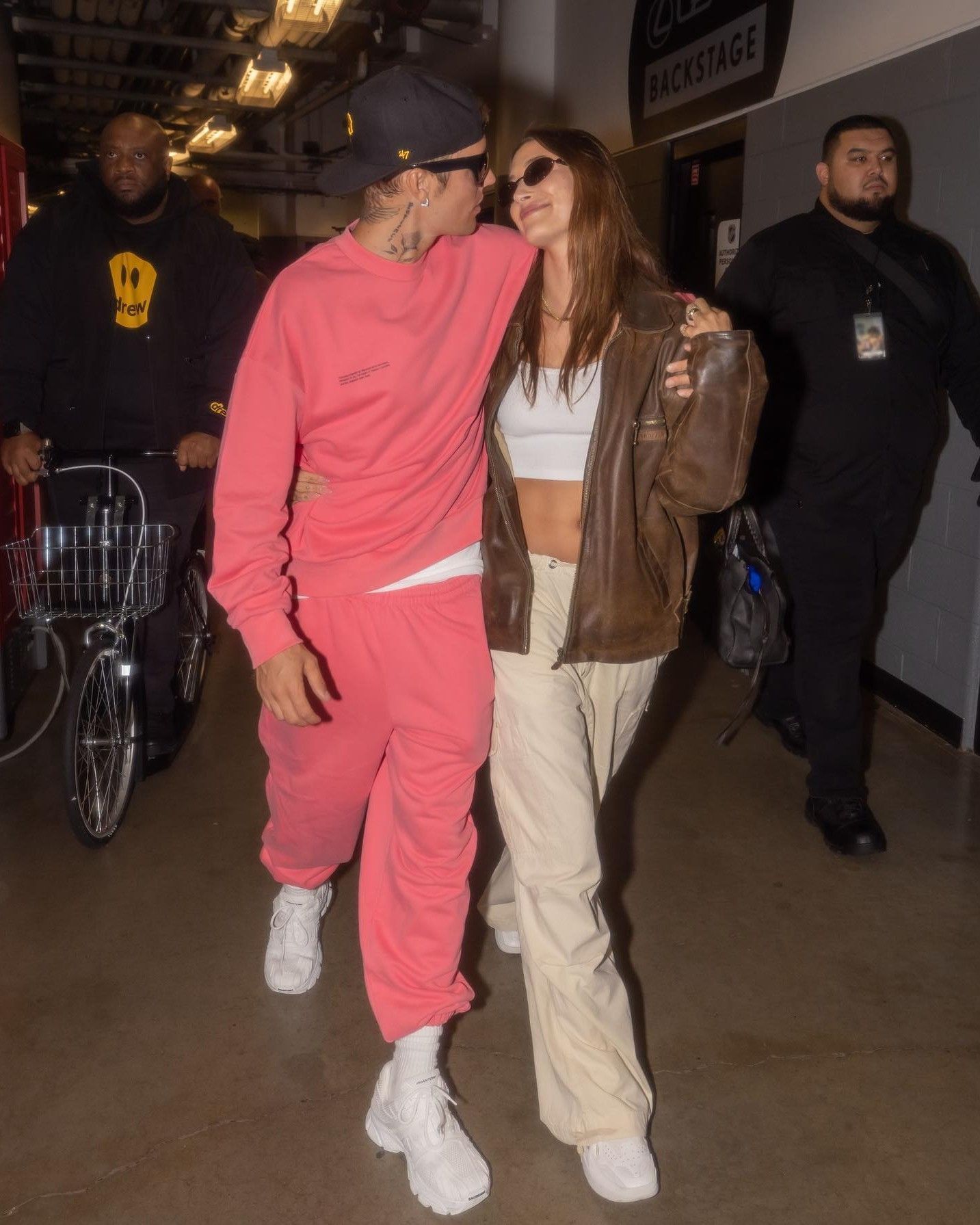

I don’t know exactly when it started, but I remember the feeling perfectly. The fear of walking into class on the first day of school, not because of the teacher or new classmates, but because of the look everyone would give to my feet. It wasn’t like that in elementary school. We ran, we played, and if you had shoes that helped you slide better on the asphalt, you were already at the top. But in middle school, everything changed. The world started to split between those who had TNs, Silvers, Total 90s and those who didn’t. And I didn’t. First day, first glance. A quick look at my shoes, an expression that said it all. A faint smile from those who knew they were on the right side of the barricade. It didn’t matter if we were friends the day before, if we had played together in the courtyard. What mattered was what you wore, what you showed you could afford. Air Maxes were everywhere. Even those without TNs at least had those. Not me. I had no-name shoes, soles that didn’t squeak in the hallways, that didn’t leave footprints of respect behind me.

That feeling of being watched, judged in just a few seconds, stayed with me for years. Just a glance at your shoes could determine who you were, whether you deserved to be heard, whether you could hang with the cool kids. An invisible brand you wore before you even opened your mouth. I often wonder why it was so important. Why the symbol of respect came from a pair of shoes and not, perhaps, from how you treated others, from what you said, from how you moved through the world. But in the end, the answer is simple: they weren’t just shoes. They were belonging, status, protection. They were a signal of who you were before anyone gave you the benefit of the doubt. And it’s not something that only concerns kids. Growing up, I realised adults do the same, just with different codes. With watches, cars, clothing brands. The difference is that in middle school, no one had filters: judgment was direct, brutal, without diplomacy. I spent my afternoons imagining myself wearing a pair of black Total 90s with silver details. Not because I really liked them, but because I knew that was enough to not be a target.

And as soon as I got my first paycheck, guess what the first thing I bought was?