Why are the fashion week shows shrinking? In times of crisis we tighten our belts - along with the guest list

Intimacy and grandeur – which of the two makes a fashion show work? Many brands (and consequently many PR and production agencies) must have asked themselves this question this FW25 season that is about to close, and in which, in addition to fashion trends, trends in the organization of shows themselves have emerged. On one side, there have been mega-shows by Valentino and Balenciaga, but also by Courreges in Paris; and those of Fendi, Diesel, and Dsquared2 in Milan – on the other hand, the intimate and whispered presentations of brands like The Row or Tom Ford, but also the show by Givenchy and especially the much-discussed, frequently visited presentation of Loewe in Paris, where both big and small fashion personalities went to pay homage to Jonathan Anderson's latest (presumably, but now it seems settled) collection for Loewe. In general, the two different ways in which a show has been organized follow two different approaches: the blockbuster show aims to maximize visibility on social media; the intimate one focuses on craftsmanship and luxury. In the case of the "small-scale" shows, however, which have multiplied this year, a problem has emerged, as reported by Vogue Business in a recent article, and that is the issue of editors and fashion workers being denied an invitation or asked to attend the show standing or, as it’s said in Italy, “in the pigeon loft,” to underline how standing represents in part a kind of consolation prize. According to Vogue, however, the shift in show capacity is becoming alarming: from the classic 500 or 1000 seat shows, we’ve moved to shows like Givenchy and Tom Ford’s, which only had 200-300 seats, and we’re not talking about small independent brands, but major historical brands and two of the most anticipated debuts of the season.

@fashi0nd0ll Tom Ford's Fall/Winter 2025 Paris Fashion Week #parisfashionweek #fw25 #Runway #tomford #foryou #fyp #foryoupage #TikTokFashion #fashion #model original sound - Franklin Saint

Both Burton and Ackermann emphasized, respectively to Vogue Runway and to New York Times, that they wanted to make their shows more intimate - Hackermann also added that, in his opinion, true luxury should not be universally accessible. But Louis Vuitton and Schiaparelli also opted for less huge shows this year. Duran Lantik, for his part, held a show for only 200 invited guests. The Row’s audience was probably even fewer. The only issue is that fashion is a business of relationships: when choosing who can enter and who can’t, it’s not only necessary to be extremely careful not to step on anyone’s toes but also to balance the presence of journalists, buyers, and celebrities/influencers to ensure the show has the right visibility and positioning. It should be added that, in the case of the latter category, there is also the added logistical effort of collaborating with their stylists, sending looks for the show, and producing all the different content. It’s no secret that now, for numerous shows, in addition to sending show notes and runway looks to the press, more and more brands also include photos of the front row and guests, which often become more numerous than those of the show itself. When it comes to the press and buyers, however, you do what you can: you invite the heads of publications, showrooms, and retailers, with other invites going to the re-see – those covering for social media, on the other hand, have free access to backstage and the front row, but usually not to the shows. According to Launchmetrics data, reported by Vogue, the media value of a single seat at a fashion show can be worth up to 77,000 dollars in terms of mentions in articles, social media interactions, and overall visibility generated by a participant.

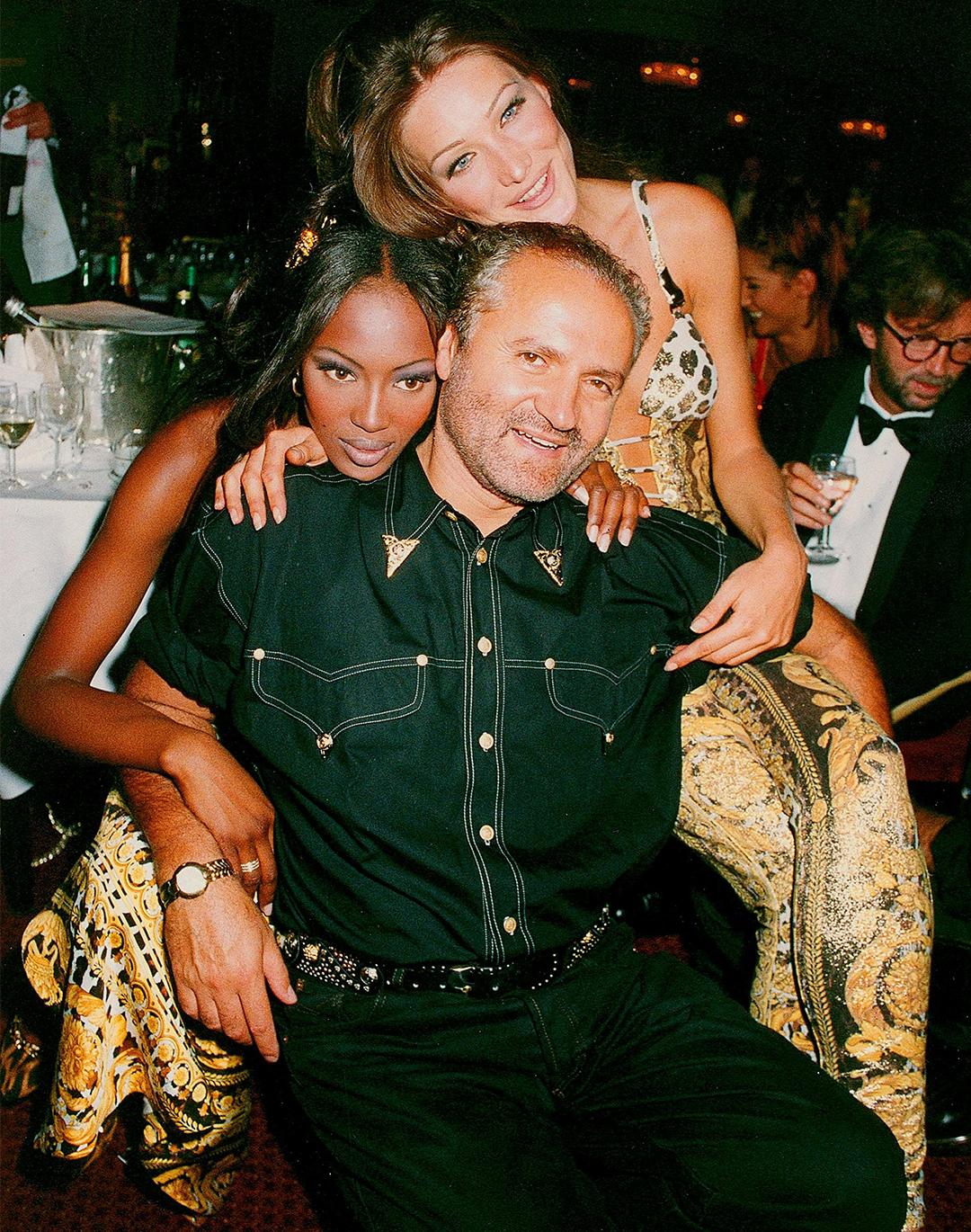

The issue is not only an aesthetic and presentation approach, but also, quite simply, costs. Fashion shows can cost hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of euros, and many brands are economizing: fewer spectators but the right spectators allow for less expenditure in terms of set-up and location, more targeted investments in talent. With sales declining, and a clientele aging due to issues related to purchasing power, inviting and paying celebrities from Gen Z who bring visibility but not sales is an investment increasingly subject to reconsideration. An older clientele, in fact, needs to be seduced with other methods: a visible trend starting from recent campaigns like those of Zegna and Burberry is that the focus on heritage and quality goes hand in hand with the appearance of more mature faces both in campaigns and on the runways. The return of numerous top '90s models in recent shows in Milan and Paris also seems to point not only to an “ideal customer” that is more âgé, but also to the inclusion of faces that those less connected to the world of social media can easily recognize. One must at least be familiar with TikTok to appreciate Alex Consani or know who Noah Beck is – but everyone knows who Naomi and Carla Bruni are.

@nssmagazine Take a closer look at Schiaparelli FW25 show in Paris. Which one is your favorite look? #parisfashionweek #pfw #paris #runway #fashiontiktok #tiktokfashion #gigihadid #alexconsani #monatougaard #schiaparelli #fashionshow lilacs - slowed - velours & azrxel & abxddon

Another interesting theme raised by Vogue Business is that of media overexposure: The Row generates more anticipation and attention with a photo ban and a lookbook published days later than many other brands manage to do, spending considerable sums and creating a lot of noise on social media, often fueled by very devoted fanbases that rarely turn into customers. And according to the data from Lefty and Karla Otto, Dsquared2 generated 16.2 million dollars in EMV with its mega-show, but it’s also true that Bally, with its 100 invited guests or so, surpassed the visibility of both Armani and Blumarine. It’s clear, of course, that the format of the fashion show is not changing and won’t radically change. For Blazy’s debut at Chanel or the next creative director of Gucci, whoever it may be, we can still expect mega-shows. The same goes for many other brands that have become giants in the market, like Dior or Prada, but also Diesel, which bases much of its popularity on an accessible format (via more or less telematics) just as its prices are accessible. And perhaps this shift in direction in the shows, as well as the de-investment movements we are currently observing only in a few segments of the industry, together with the shortening of the supply chain evidenced by the constant acquisition of local manufacturers by mega-companies (the latest being Chanel) is part of a parabola of downsizing for a luxury industry that has reached its peak growth and now needs to figure out how to stabilize. Will a smaller fashion also be a better fashion?