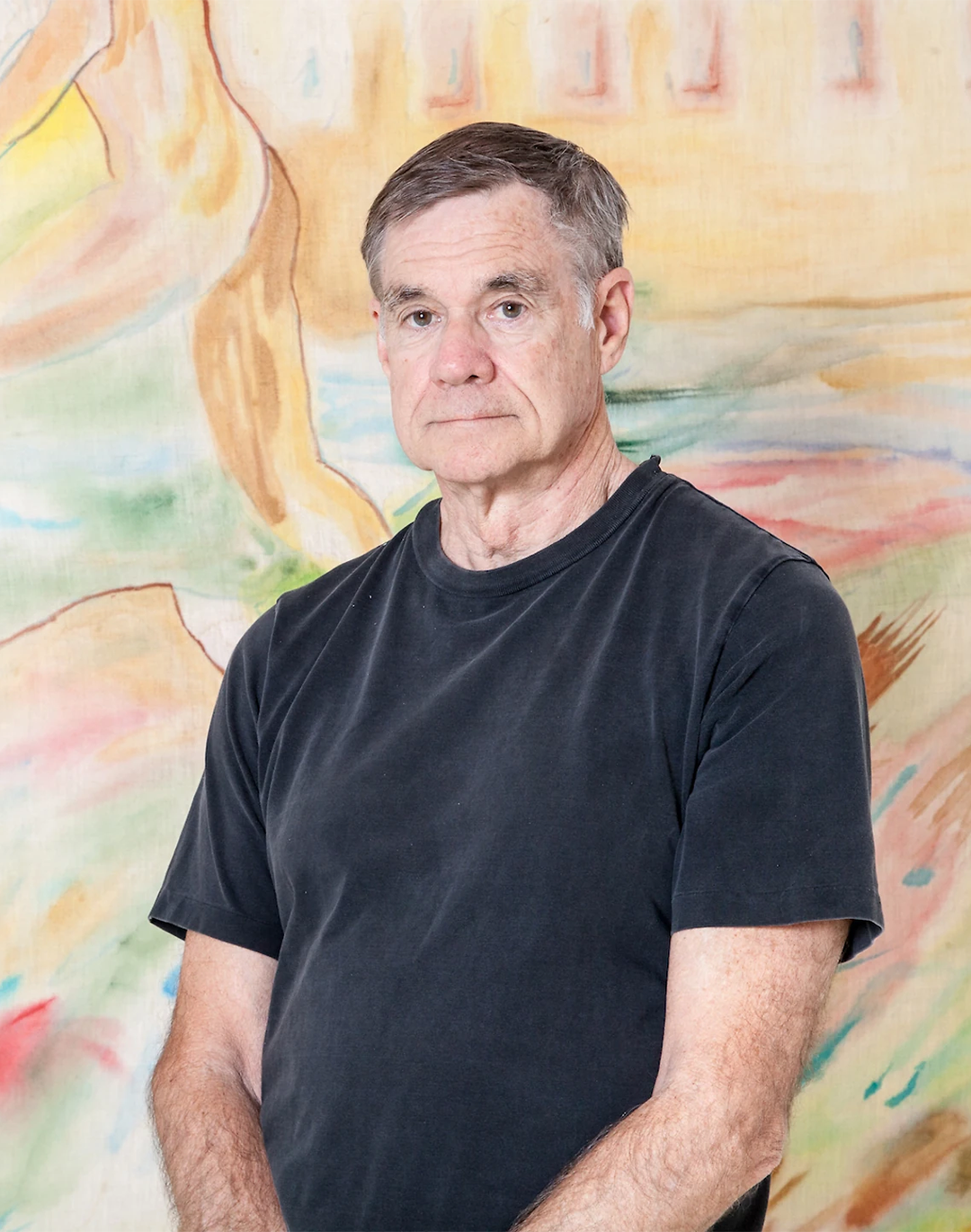

The three pillars on which "28 Years Later: The Bone Temple" is built First and foremost, Doctor Kelson portrayed by Ralph Fiennes

There are three pillars on which 28 Years Later – The Bone Temple is built. The first is its true protagonist, Dr. Kelson, played by Ralph Fiennes, the second is the villain portrayed by Jack O’Connell, and the third is Nia DaCosta—and the reason why she was likely chosen to direct the sequel (itself a sequel) to 28 Years Later from 2025. Let’s start with the latter. Returning to the saga after twenty-three years, Danny Boyle had (once again) taken the reins of the universe plagued by a powerful virus that turns people into zombies, a world many wished to see brought back to cinemas through a new trilogy.

The British director, working from a screenplay by long-time collaborator Alex Garland, has enormous fun crafting a film like 28 Years Later, where, by his own admission, the main goal was to combine themes such as Brexit and the Teletubbies. Something he successfully achieved, playing extensively with the film’s texture, which constantly shifted in nature, format, and style. Its schizophrenic editing (by Jon Harris) brought together all the narrative and technological ideas Boyle wanted to include, creating a cinematic hybrid between classical filmmaking and video-game simulations—fragmented, then reassembled with restlessness and urgency.

With 28 Years Later – The Bone Temple everything changes, even though Garland remains as screenwriter. The story moves from a coming-of-age narrative to one centered on faith; from constant shifts in perspective to a more linear and cohesive direction and gaze; and from the teenage protagonist Spike (Alfie Williams) to the doctor played by Ralph Fiennes. Both were present in the previous chapter, though in almost inverted roles. If Spike guided the narrative before, now it is the turn of Ian Kelson, master of the solemn ossuary where we find him once again. The doctor takes charge of a new companion—or at least he tries. The Alpha encountered in 28 Years Later by Danny Boyle becomes a test subject in Kelson’s attempts to change the course of the virus by finding some form of antidote. A desperate effort in desperate times. An experiment carried out under the doctor’s constant reminder, *memento mori*—the maxim not to forget that sooner or later we must die, something hard to ignore when surrounded by zombies.

Ralph Fiennes brings deep commitment to the role of Dr. Kelson, both physical and human. He conveys the man’s intelligence and resilience; as well as the madness of spending years building a true mausoleum, raising skulls and skeletons to honor a world adrift. A testimony to life in a territory now inhabited only (or mostly) by death, with Dr. Kelson becoming the guardian of the memory of a people, of an ordinariness that no longer exists and that has long distanced him from any semblance of normality. Fiennes holds nothing back—neither in intensity nor when it comes to staging the body. There is a spark in his eyes that stands out against the orange skin colored by iodine to defend against the virus, along with a body the actor places at the film’s service, just as Kelson placed himself at the service of his patients and, later, the dead. A body that reveals itself, that undresses and, when needed, adorns and costumes itself. A body that dances the madness of a world where beliefs still exist even when everything else has collapsed. And who knows whether it is more insane to trust in tomorrow or to have no faith at all.

@sonypictures.it L’orrore cambia forma. Stavolta ha un volto umano. 28 Anni Dopo: Il Tempio delle Ossa, dal 15 gennaio al cinema. #28AnniDopo suono originale - Sony Pictures Italia

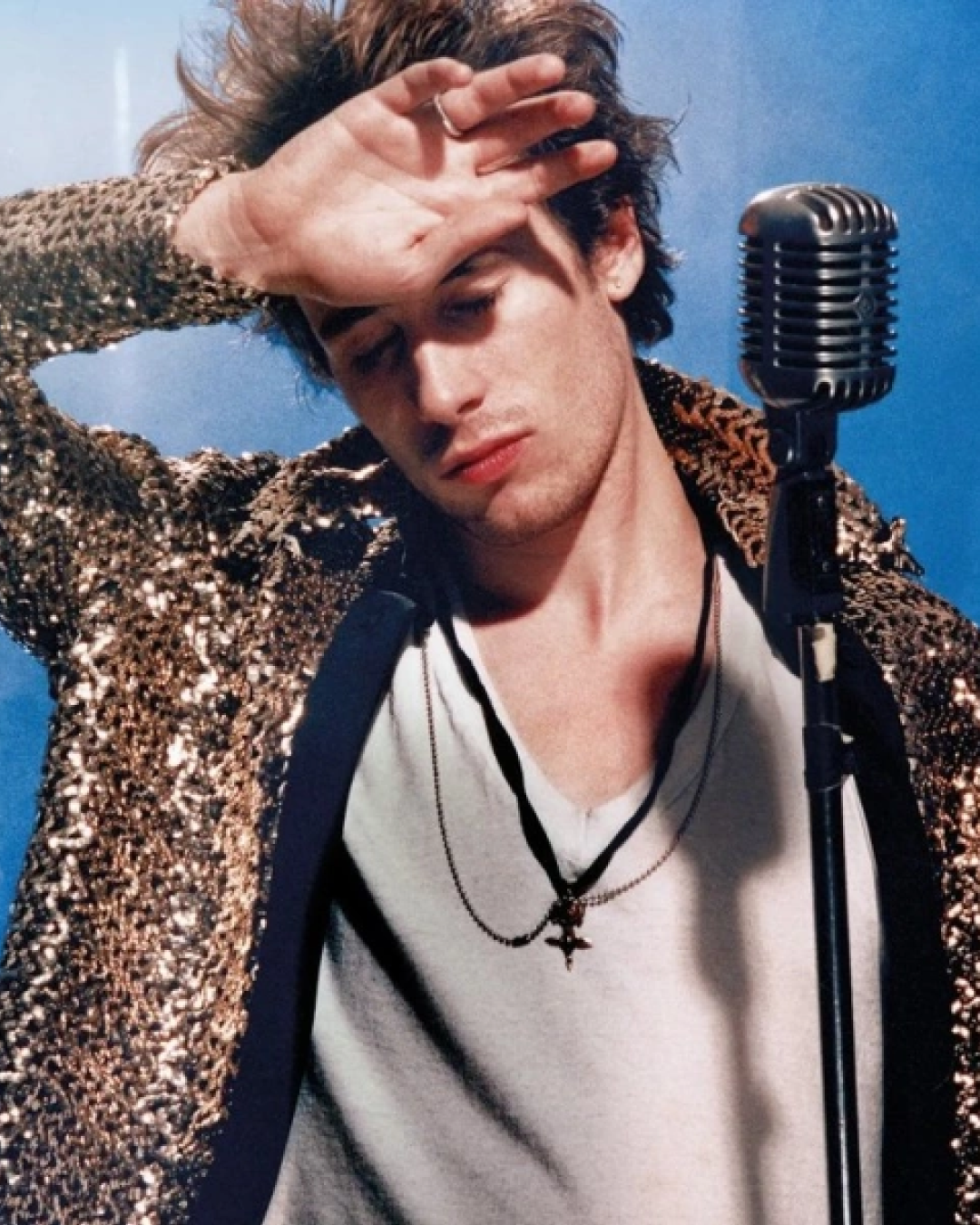

Which brings us to Sir Jimmy, played by Jack O’Connell, who channels myths, stories, and religions. First appearing in 28 Years Later as a child and returning at the end as an adult with all his imbalances, the character exemplifies how fear and despair are the greatest engines any leader could hope for. A lesson easily learned from history books or daily news, yet one that Garland and DaCosta reframe within their horrific cosmos—specifically within the congregation he leads. Sir Jimmy, wearing a jumpsuit and crown, has convinced some young followers that he is none other than the son of the “old goat.” The Devil, Lucifer, Satan—who speaks in his ear and whispers what must be done, which usually translates into slaughtering anyone the group encounters.

The character is an ambiguous figure. A child who suffered personal trauma and grew up likely developing a disorder. He hears voices in his head, voices that turn into brutal, murderous commands. The film never asks for, nor inspires, pity toward him, yet it is clear that Jimmy is the product of two external forces he could never truly control (hence his attempt to command now): the religion imposed by his family—especially his father—and a world plunged into hell on Earth, which he experiences as a punishment all men and women must endure. And this, circularly, leads us back to why we find Nia DaCosta behind the camera.

@candymanmovie I heard you’re looking for #Candyman original sound - Candyman Movie

With a currently varied career—from The Marvels in the MCU to the theatrical adaptation of Henrik Ibsen with Hedda—the American director and screenwriter also has in her portfolio another horror film that, like this sequel, explores the landscape of legends, here transformed into cults. That film is Candyman (2021), a direct follow-up to the 1992 cult classic, in which street stories and urban tales fuel people’s imagination, becoming more tangible than ever. An investigation into the power of imagination and how it strengthens when believed in so deeply that it gains a body—providing explanations for what does not exist, or even comforting answers to painful, impossible questions.

Candyman, both the Nineties film and the version directed by DaCosta, feeds on the idea of stories and characters becoming vessels for people’s fears, as well as catalysts for guilt and shame. Something similar happens in 28 Years Later – The Bone Temple. Sir Jimmy has followers to whom he murmurs and delivers the orders of the ruler of the underworld. No one has ever seen the old goat, yet everyone assumes he exists. Perhaps the film almost unmasks Jimmy, but one senses he is driven by a conviction that may waver yet never fully collapse. Faith, for better or worse, is the engine of the work—a horror that shows how believing is the most important thing, on one hand to maintain control, on the other simply to stay alive.

On these three foundations rises 28 Years Later – The Bone Temple, connected in its own way to the first film yet completely different in style, themes, and resolutions. Coherent though not resembling its predecessor, it belongs more to a sensibility already explored by Nia DaCosta—one made of myths, handed-down tales, and inventions, all with the single purpose of helping us find a way to survive.