BlackStar Theory: was David Bowie’s death a work of art in itself? Reflections and theories ten years after the passing of the English singer

Exactly ten years ago – on January 10, 2016 – just two days after his 69th birthday, David Bowie passed away. No one outside his close circle of trust knew he was ill. Perhaps for this very reason, his death unleashed a wave of mourning even more intense than one might have expected for a star of his stature.

In a year marked by many significant losses in the music world (among them Prince and Leonard Cohen), David Bowie’s death was undoubtedly the one that left the deepest mark. There is an explanation that goes beyond the immense affection fans felt for the English singer: just two days earlier, on January 8, 2016, his final album, BlackStar, had been released. A record that resonates with the death of its author in an unprecedented and difficult-to-articulate way: not unsettling, but rather like the final luminous trail of a dying star taking its bow in the sky before departing.

In a statement released shortly after his passing, long-time friend and historic producer Tony Visconti declared that he had known about Bowie’s health condition for a year, adding that "his death was no different from his life: a work of art". If this work and the sequence of events surrounding it were indeed conceived as a grand farewell design, then David Bowie was certainly the first artist to attempt and accomplish something so audacious with such precision and clarity.

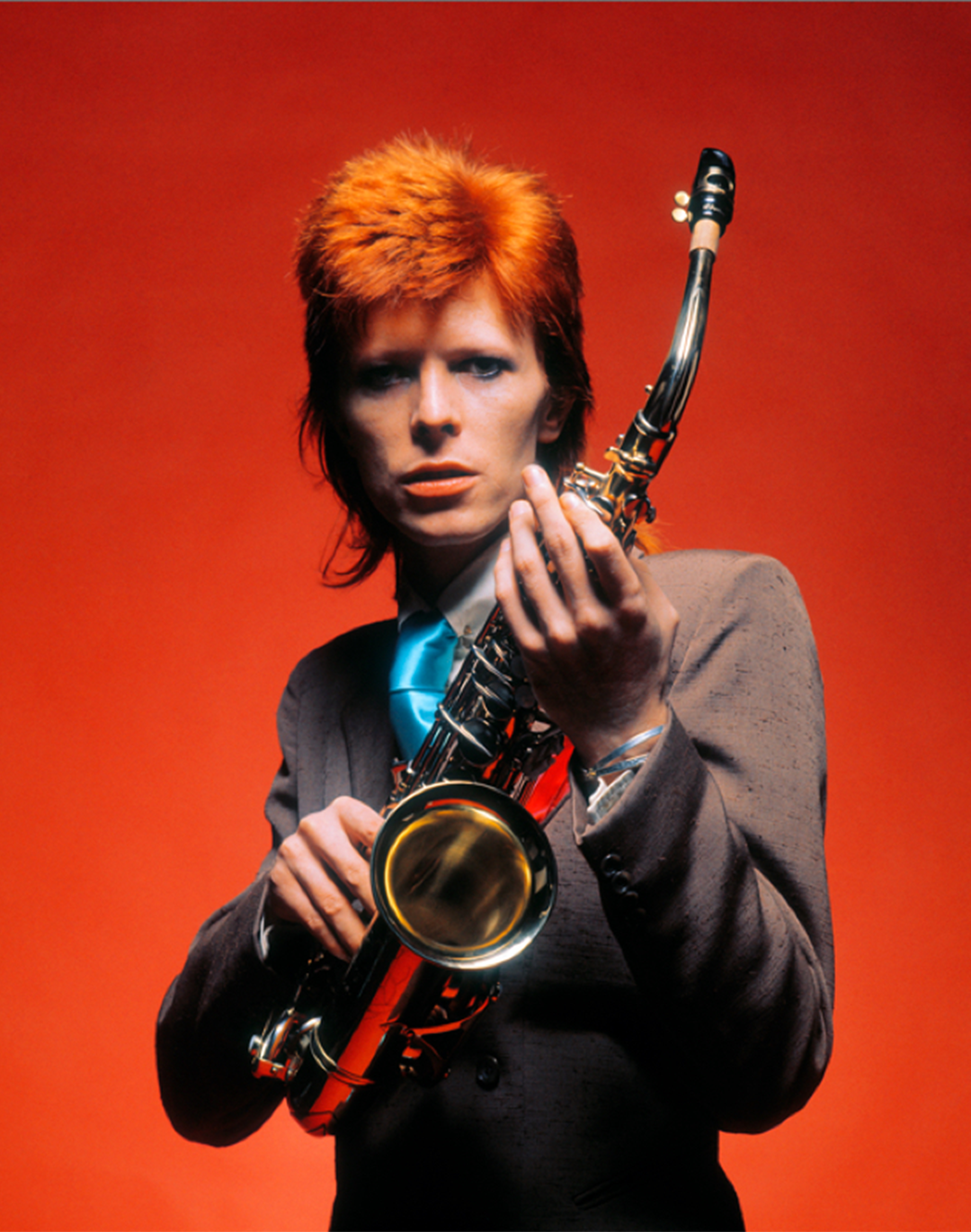

It is not easy to demonstrate, but there exists an essay by author and musician Leah Kardos – titled Blackstar Theory: The Last Works of David Bowie (unfortunately still unpublished in Italy) – which attempts to investigate the matter. Based on the study of Bowie’s late works, that is, the production spanning from 2003 to 2016, Kardos explores the perspectives of identity and death of the star Bowie. In this regard, Bowie’s catalog has always been rich in deadly imagery (distopian visions, murders, suicides, etc.), but while in the past such reflections had a certain theatrical distance (think of the killing of the Ziggy Stardust character), his late works seem to possess a more authentic emotionality.

In her essay, L. Kardos primarily examines three works: the 2013 album The Next Day, marking Bowie’s “return” after a nine-year hiatus; the theatrical production Lazarus, staged for the first time in 2015; and finally his ultimate farewell album: Blackstar. The analysis follows a structure inspired by the three-part theatrical illusion concept, as described in C. Priest’s novel The Prestige (1995), adapted for the screen by Christopher Nolan in 2006: first (1) the setup = The Next Day, then (2) the performance = Lazarus, and finally (3) the prestige trick = BlackStar.

1. The Next Day: The Setup

@davidbowie Where are we now? #davidbowie #bowietok Where Are We Now? - David Bowie

The Next Day lays the foundation for Bowie’s “late style”, obsessed with aging, mystery, and the remystification of his image. For much of his career, Bowie was a transformative innovator, a mask constantly changing, but towards the end of the 20th century he changed his costume one final time: seemingly withdrawing from the frontiers of the new and stepping back from incessant reinvention, "he became more ordinary than ever,” performing a public version of himself that appeared more in line with the "real David Jones” hidden behind the “David Bowie mask”.

In the context of a David Bowie “seen as a normal human aging”, the close interplay between reality and fiction led to musical interpretations more attentive to the man than the myth, raising the suspicion that Bowie might reveal something private about himself. The album’s lead single – Where Are We Now? – inhabits this blurred space, where the singer is presumed to be the 2013 Bowie, taking stock and contextualizing his existence in terms of a past that exists both in Jones’ reality and Bowie’s myth. In the album’s title track, “the old Jones factor” seems even more pronounced: "Here I am/not quite dying".

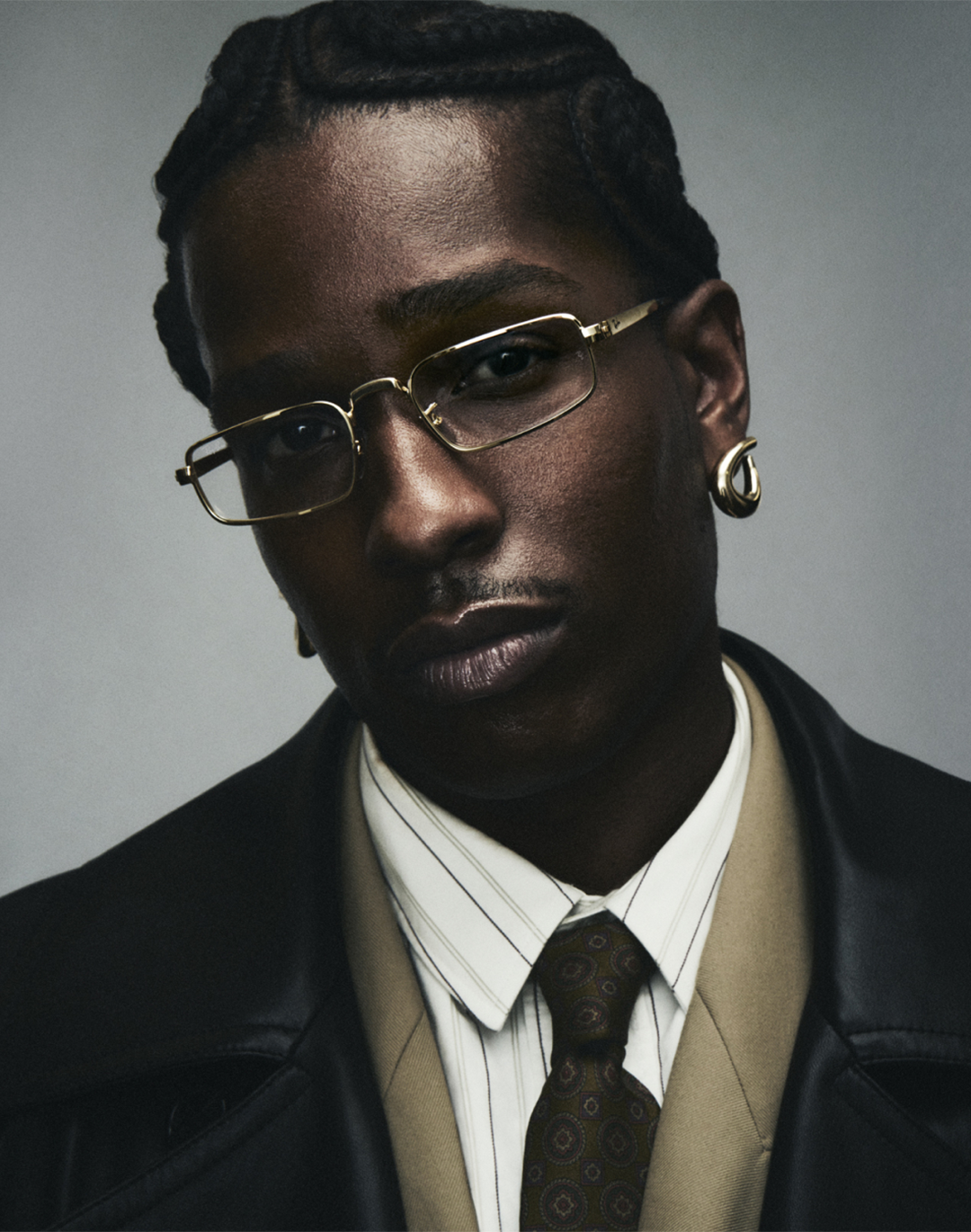

Conversely, in a mirrored and opposite manner, Bowie’s refusal to participate in 21st-century celebrity culture helped to remystify the “Bowie brand”, with the progressive withdrawal of the David Jones persona and a new reassertion of the mythical figure of David Bowie. Practically, Bowie returned in 2013, but was elusive, giving no press statements and no interviews. The closest explanation for The Next Day is a list of forty-two words sent to writer Rick Moody at his explicit request. Bowie thus became a new text to decipher, a language to understand, a puzzle to fill. Not coincidentally, on the cover of The Next Day, the iconic image of Bowie, taken from the Heroes (1977) cover, is obscured by a white square.

There was a time when every Bowie album had a new and appropriate visual style: here, that dimension is rejected. Instead, there is a riddle about the artist’s identity. The same type of riddle proposed by the exhibition David Bowie Is, inaugurated at the same period, aimed to contextualize the 2013 Bowie in relation to the objects and memorabilia of his history. The exhibition, like the album, invited the audience to construct their own image/idea of who or what Bowie was, relating him to elements from his past.

The Next Day also revisits the star metaphor, widely used by Bowie throughout his career. In the video for The Stars (Are Out Tonight), directed by Floria Sigismondi, the “stars” are celebrities hunting at night, desperate creatures exploiting the anxieties and desires of "ordinary people." The stars in The Next Day are thus far from the cosmos and much more terrestrial—they are the celebrities of late capitalism, among them Bowie himself, who here is a Rock Star or Pop Star, but not yet a BlackStar.

2. Lazarus: The Performance

In December 2015, Bowie fulfilled the dream of staging his own theatrical production: Lazarus premiered in New York and has since toured theaters worldwide. It is a complex musical, dreamlike and hallucinatory, criticized for being too enigmatic. The plot is conceived as a hypothetical sequel to Walter Tevis’ novel The Man Who Fell to Earth (1963), adapted by Nicolas Roeg into the 1976 eponymous film, starring David Bowie as the alien Thomas Newton. In the book and film, Newton fails to save his home planet and becomes trapped on Earth, ultimately isolating himself, lonely, alienated, and addicted to alcohol. In the stage production, Newton somehow battles with himself until he frees himself, finds death, and returns among the stars.

The title of the show has little to do with the biblical Lazarus (symbol of resurrection), but other points of reference exist, from poet Emma Lazarus (symbol of immigrant welcome) to Lady Lazarus, the poem by Sylvia Plath in which the famous poet, having died by suicide, subverts canonical perspective and presents death as a blessing. This concept is introduced in Bowie’s Lazarus from the beginning. A peculiarity of his Newton is that he cannot die. Newton expresses his condition with irritation in the opening minutes: "I am a dying man who cannot die...".

Bowie, staging Newton’s death in the finale, connects to the Buddhist notion of a “good death”. For Buddhists, the Tibetan Book of the Dead provides a guide to the transitional states consciousness must pass through between death and subsequent rebirth. These stages include the “painful moment of death,” the “vision of wrathful deities,” and the “karmic event of becoming.” The purpose of these experiences is to assist the transformation of an individual’s consciousness, often through dramatic manifestations of hallucinatory psychic projections (just as seen throughout Bowie’s show), to purify excessive karmic content before the next life.

Added to this is the overlap between Newton and Bowie. Those familiar with the singer’s biography know how strongly Bowie’s identity was intertwined with that of the “alienated alien” at the end of the 1970s, when Bowie himself was in the grip of hallucinations and substance dependency. The director N. Roeg stated that Bowie’s skill in performing the role stemmed from the fact that he was, in essence, playing himself. In the finale of Lazarus, Bowie stages the death of himself, turning it into a work of art that continues even after his real departure.