Is it really true that kind people earn less? Power, perception, and the mirage of a gentle future

In the book What is Power, the Korean philosopher Byung-Chul Han teaches us that power is invisible, that it does not impose but seduces, moving through our lives by means of consent. It can manifest itself every day – in the office, in a WhatsApp group, during the Monday morning call. In this system, kindness has become an obstacle: those who cannot attack are left behind, emotionally and perhaps even economically. Yet kindness could save us, acting as a mechanism of cultural resistance.

The relationship between power and kindness is a broad and complex topic when related to the professional sphere, especially in the creative sector. A study conducted by Oliver Scott Curry (Oxford University and kindness.org) shows that in a society obsessed with efficiency, kindness loses economic value but gains social value. Sacrifice, not usefulness, becomes the measure of sincerity.

Kindness pays less because it does not generate profit, but rather trust, a relational and not economic currency. In recent months, the theme of kindness has become a central trend in podcasts and online content, where content creators and hosts recommend it to their audiences as a way to overturn contemporary values and bring them into the professional sphere. But it’s a very radical kind of work and must be approached consciously, not as a performative act.

Power, like kindness, also works according to a logic of interdependence. Those who collaborate, who listen, and who show availability do not renounce power: they redistribute it and make it circulate. In complex systems – from creative work to cultural leadership – kindness does not eliminate power, but humanizes it and makes it practicable. As regimes and heads of state increasingly resemble true dictators, the link between power and economy proves indissoluble. We see it every day, even during work hours. Being too kind can become counterproductive, especially if the system rewards those who impose rather than those who listen.

Society, understood as a machine of power, constantly reminds us of this: in politics, authoritarian leaders are promoted, while at work, those who advance are often the ones who can simplify everything in a single direction, those who know how to impose their command on others. Figures with a strong tone and «bold» behavior – to use a term much loved in Milan – reassure superiors and reinforce the same hierarchies that make kindness a flaw. Those who instead favor complexity, in an old-fashioned idea of a system where time equals money, are penalized because they are perceived as unproductive.

A person can be kind by nature, by upbringing, or because they believe that relationships with others should be guided by a code. Recently, however, what has prevailed is roughness. Social media increasingly represents this trend: raising one’s voice has become the only possible language, made of bold titles and reversed strategies, like rage-baiting, which exploits outrage to generate engagement. The speed with which we communicate, even in everyday matters, has convinced those in power that being kind means being unproductive, with calm and composure now interpreted as shyness or reluctance.

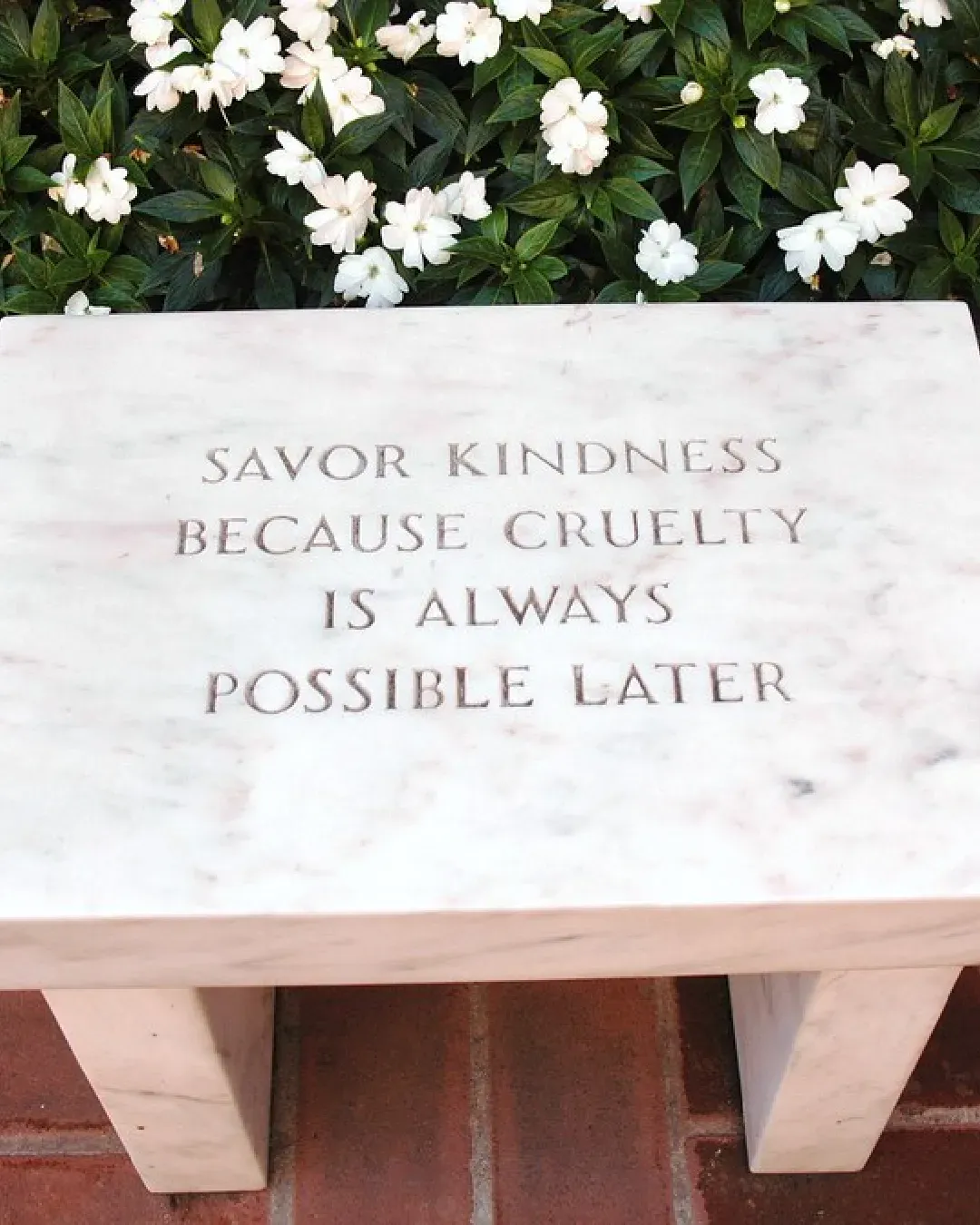

In creative work, kindness does not pay; it is a symbolic currency in an economy that only accepts performance - but today, more than ever, we need it. One is reminded of the phenomenal work of Jenny Holzer, one of the most important artists of her generation, with an excerpt from the Survival Series (1983–85): Savor Kindness Because Cruelty is Always Possible Later.