Enzo is a social drama between delicacy and disillusion Warmth, bodies and feelings: the summer of a young protagonist looking for his own place

It’s hot in Enzo’s summer. The construction workers’ bodies are covered in lime and sweat as they build a new villa in the seaside town of Ciotat, near Marseille. The heat rises, whether from the scorching sun or the protagonist’s growing closeness—who gives the film its name—to his coworkers’ bodies. One in particular: the young Vlad, of Ukrainian origin, who fled his homeland—where his friends still live and fight—in search of a better life. But the heat that gets to your head is also a sign of Enzo’s restlessness and youth, especially when he must deal with his parents, particularly his father, and their privileged family status. Determined to be useful, to return to basics and get his hands dirty to escape his pre-set normality, the boy rejects the comforts his social class has steered him toward in favor of something more practical, more concrete—even if he doesn’t quite seem capable of it.

The theme of escape is at the heart of Robin Campillo’s film, co-written with Laurent Cantet and Gilles Marchand—so distant between Enzo and Vlad, yet so alike in the way we all try to flee from ourselves only to inevitably return. Spoiled in the way only privileged kids can be, the protagonist fits perfectly into the mold of the impatient youth who rejects his privilege simply because he can’t imagine himself without the safety net it provides. Unlike the consequences Vlad would face if he returned to his war-torn country, where his loved ones are dying and where the future is far bleaker than that of being a laborer in another nation. The difference between the two characters leads them to meet halfway. In both leaving their own status quo—so different from each other—they build a connection that exists in its own personal dimension, a new and unseen order of things.

And in this relationship, there are further misunderstandings, unexpected differences. There’s Enzo’s infatuation with his older coworker, a personal exploration of his sexuality, his desires, what excites him and what fulfills him, able to experiment with any orientation he chooses thanks to full freedom granted by his family. On the other hand, there’s Vlad’s reluctance, shaped by his background, by what his new environment expects of him, by the display of a physical, macho masculinity that hides his vulnerabilities—and who knows how much more it silences emotionally. A constant push and pull makes Enzo the summer of discoveries, the summer of reckless choices, the summer when you begin to understand who you're becoming—but maybe not entirely. It’s a rebellion only a bourgeois boy can afford, and the caution that an immigrant with a certain history must maintain to survive. And in these opposing poles, Enzo places himself with both defiance and tenderness—tones through which Campillo tells his story while handing the viewer a magnifying glass to observe the silent but powerful emotional states of his protagonist.

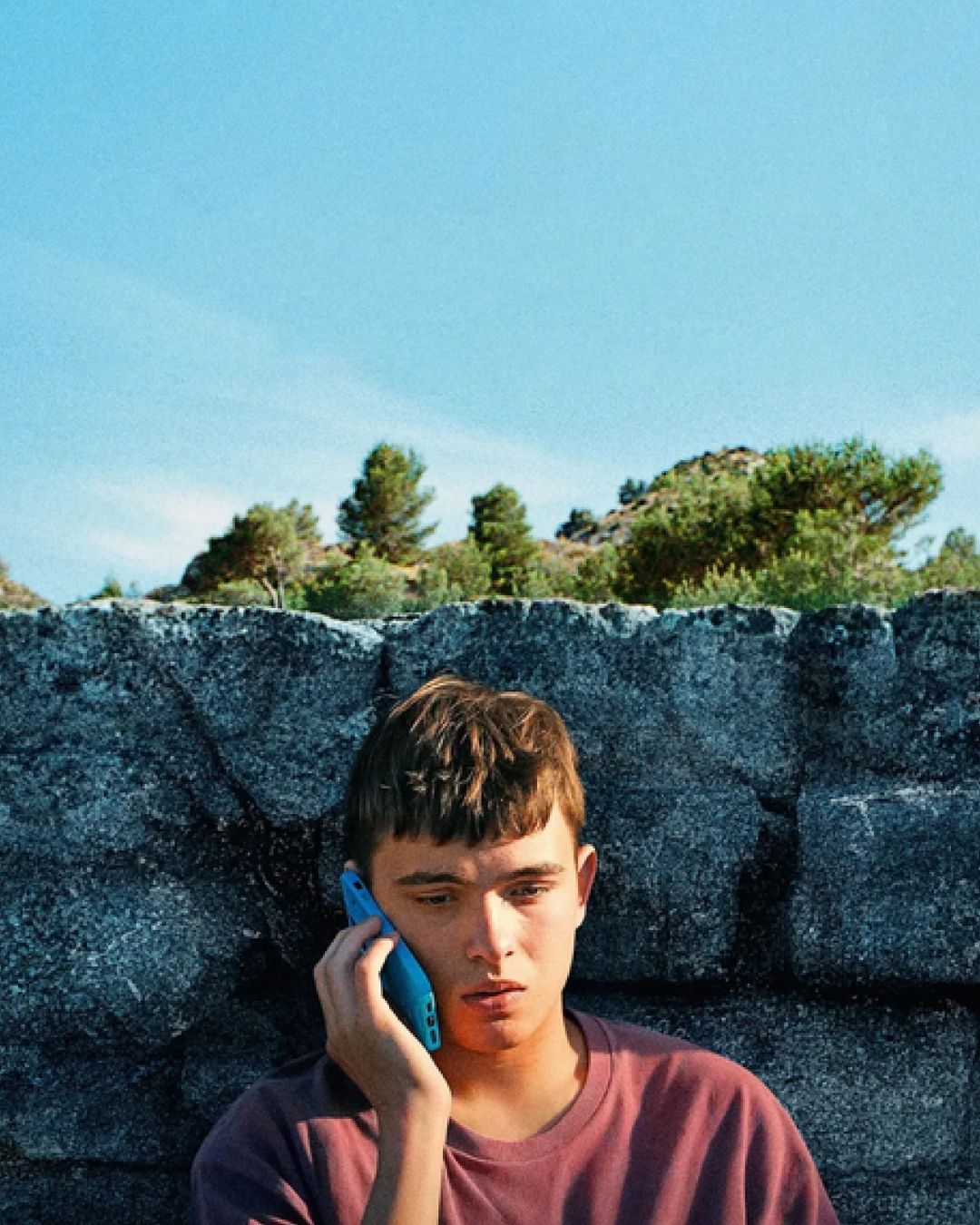

With newcomer Eloy Pohu in the role of Enzo and his object of desire played by a muscular Maksym Slivinskyi, Robin Campillo’s film begins with the construction of something new (the villa the two are working on) to build where one tries to escape from rubble (Ukraine at war with Russia) or to build something new (the protagonist’s own goal). Selected as the opening film for the Directors’ Fortnight at the last Cannes Film Festival, also starring Élodie Bouchez and Pierfrancesco Favino, *Enzo* is the state of nature we are born into and what we might become in potential. Independent and detached, free and self-sufficient. Proud and happy with what we have. But with an underlying hum that traps us—just like this social drama does: delicate, yes, but deeply realistic and disenchanted.