Third places as cultural resistance From Italy to the world, young people need space

«There is no such thing as high or low culture. High or low is always the viewpoint of the observer.»

C. Valerio

Social organization, urbanism, and human communities are the three pillars of every civilization. Since the times of Ancient Greece, when Athens created an assembly of free citizens identifying themselves as a group separate from the "barbarians," the square, known as the agora, was a multifunctional space hosting both commercial and political activities, socialization, and even cultural dissemination. In Ancient Rome as well, the Forum represented the union of urban planning and social engineering – and after all, ancient Romans, especially those from the lower classes, lived very differently from us, as the idea of spending time indoors did not exist. People ate outside, bathed outside, and socialized outside: it is only natural that the urban spaces of those and other civilizations evolved to meet those needs. Over the millennia, this concept remained: beyond the grand noble palaces and religious sites, the history of the Middle Ages and the modern era is dotted with meeting places and social hubs. Along with the church and the tavern, entire cities lived for centuries in their squares and streets – so much so that, in certain cases, like the emblematic example of Renaissance Florence, specific streets were associated with particular professions. Until the 1970s and 80s, the tradition endured: in Italian cities, it was common to see groups of elderly people spending time simply sitting together outside, and increasingly large groups of young people gathering in public meeting spots that would become, for generations to come, the "piazzette" where people met before social media and telecommunications allowed them to talk and organize remotely. An organic and progressive evolution that was abruptly interrupted by the digital era.

With the birth and spread of social media, social dynamics have irreversibly changed. By eliminating the need to meet people "analogically," social media stripped young people of the motivation to populate these spaces. Moreover, whereas public places were once designed to welcome such "gatherings", the cultural and social shock of COVID turned them into something to be avoided. The increasingly hectic pace of daily life, the dilution of the cultural identity of individual places, and the communication problems generated by social media have contributed to the decline of those third places that, five years after lockdown, young people still crave. The past world, narrower in its horizons but more manageable, has been replaced by the boundless expanse of the online world – a Babelic place where information fragments, opinions clash in increasingly incendiary conflicts, and cruelty and manipulation flourish under the protection of anonymity. It is no surprise that today we speak of the alienation of younger generations, robbed by modern society, neoliberalism, and capitalism of any physical, moral, or ideological center of gravity. These are all problems to which, as individuals, we cannot offer a complete answer. However, we can try to solve them starting from the most immediate reality: that of our cities, our streets, our third places.

What are third places?

At the core of the definition lies a 1989 theory by sociologist Ray Oldenburg, who describes the home as the first place, work as the second, and spaces of community life as third places: areas where one can relax, meet new people, and at the same time feel part of an ecosystem. Not all places dedicated to leisure are truly third places. According to Oldenburg, «third places» must have inherent characteristics such as informality and a non-pretentious nature, while encouraging spontaneous conversations among members. Think, for instance, of a neighborhood bar, a cultural center, gyms, libraries, and bookstores: all social gathering spots where people can spend time recreationally. The concept is simple and has long been familiar through media representations, like in every major 90s and early 2000s sitcom, where a bar or café always served as the main meeting point for the protagonists. In Italy, tradition has always dictated that streets and squares were the primary hubs of youth social life. For the "paninari" of the 80s, there was San Babila in Milan, while in the capital, Piazza San Calisto has been a cornerstone of the nightlife for generations. This tradition has been lost over time, due to urbanization – as in the case of Milan – and institutional efforts to control nightlife, especially in the post-pandemic scenario. At the same time, members' clubs have found new life, inspired by the Anglo-Saxon model, even in Italy. A series of circumstances and factors have contributed to a clear loss of social gathering spaces for everyone.

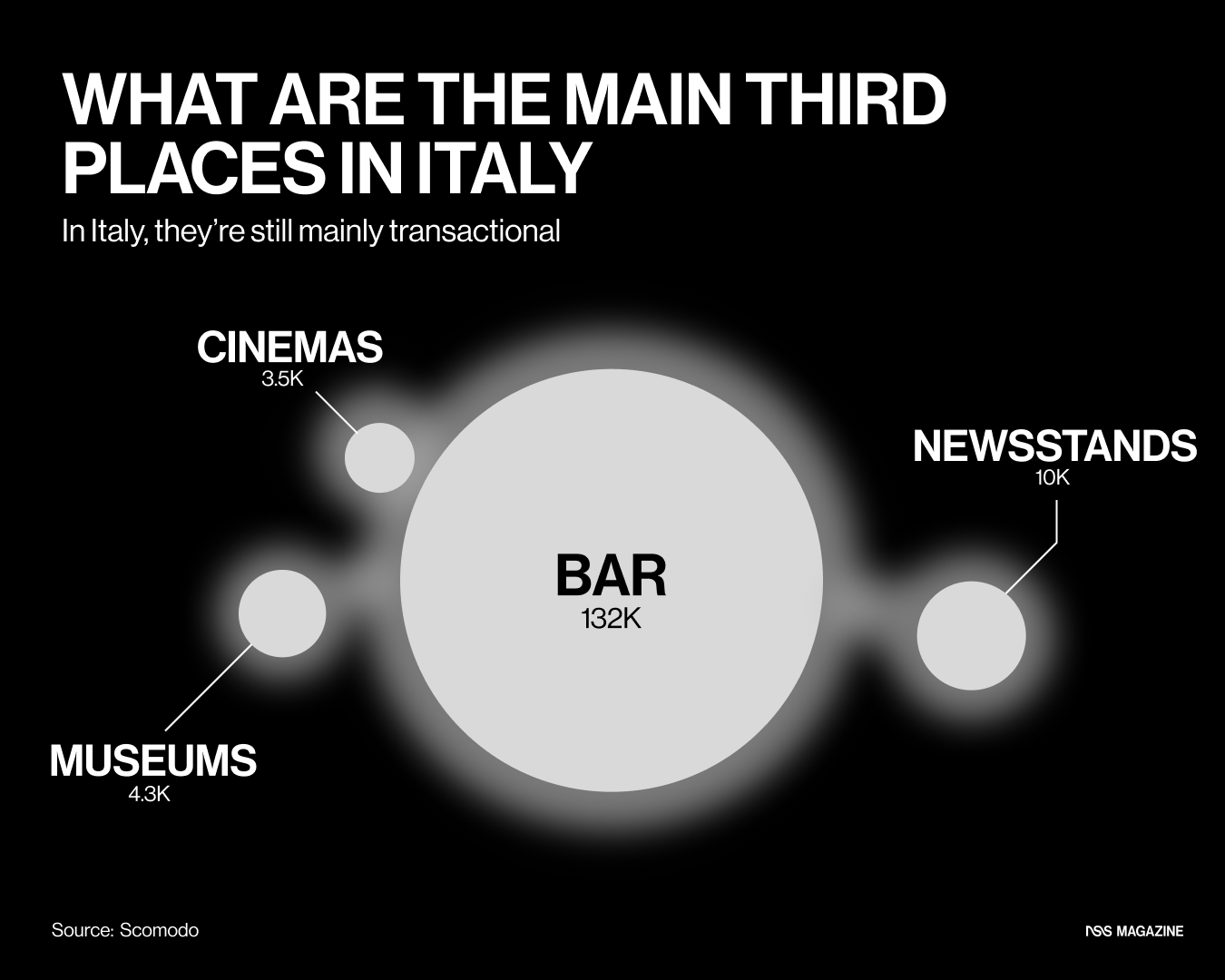

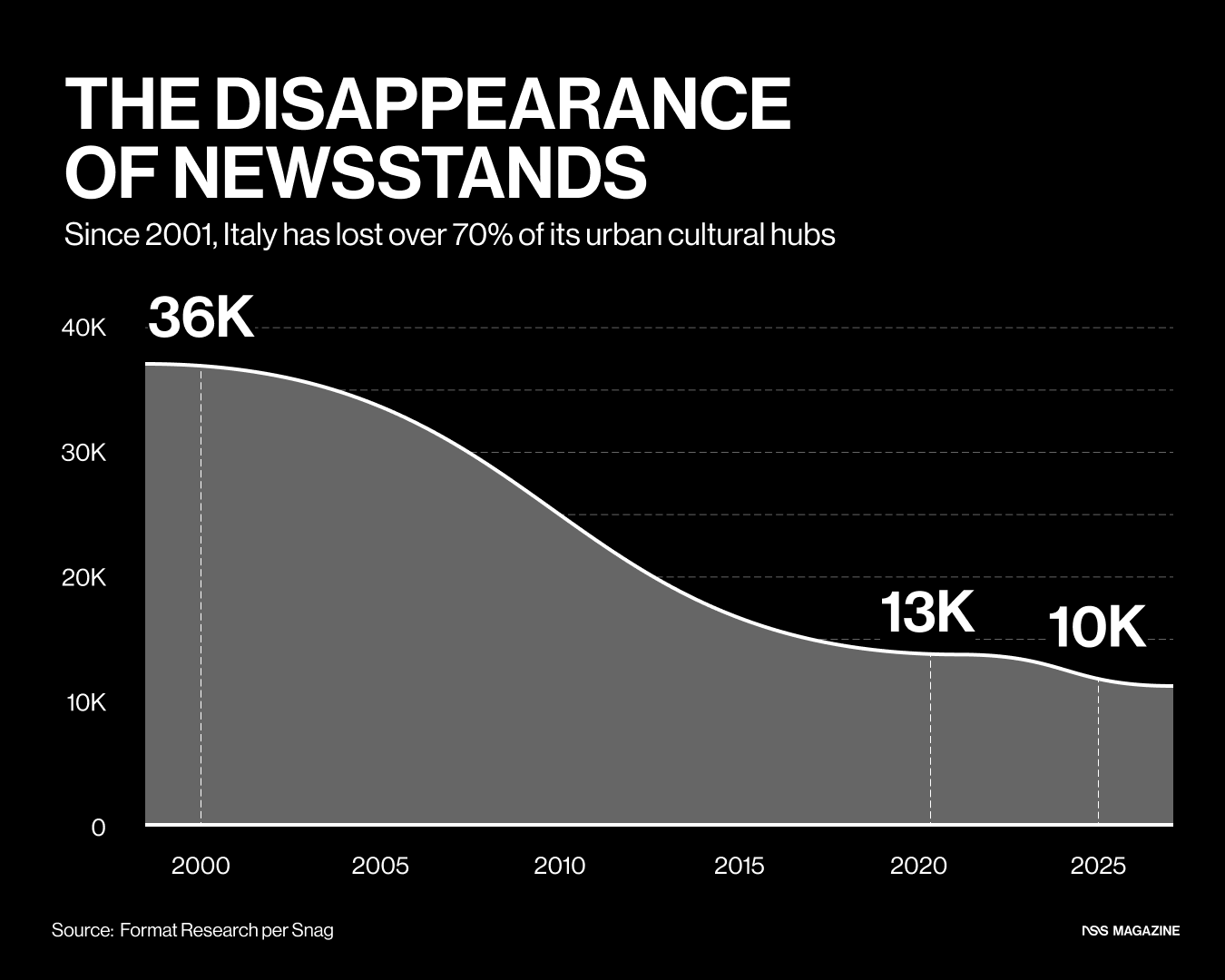

This phenomenon has been recently confirmed by Scomodo, whose analysis palpably highlights the lack of socio-cultural spaces dedicated to young people in Italy, particularly when it comes to open and independent spaces oriented toward social encounters rather than consumption. Although bars and restaurants have always been the heart of Italian social life, they possess a transactional nature that clashes with the economic reality of Italians under 30. There’s also the cultural aspect (in its most essential meaning): in food establishments, conviviality often centers around light and at times frivolous chatter. Here, too, another issue regarding Italian third places emerges: Scomodo points out that while over 132,000 bars and about 3,500 movie theaters are registered nationwide, there is no reliable data on free and independent social spaces dedicated to youth socialization. This is where we begin to venture into the complex and fragmented reality of Italian youth.

To create culture, young people need the right spaces

The main criticisms adults direct at the new generations concern their supposed disinterest in culture and their passionate attachment to phones and social media. However, while part of this problem stems from the pandemic years, lockdowns, the rise of TikTok, and algorithmic pressures, it must also be acknowledged that creating culture requires spaces — and these spaces are increasingly scarce. Nightclubs and cinemas are closing down, nightlife is becoming too expensive, and relationships are increasingly fluid (to the point that we speak of a relationship recession). How can young people cultivate their minds, expose themselves to new ideas, and engage with those who think similarly or differently if they don't know where to do it? Culture, understood as the development of knowledge, can be a tool for connection and unity among new generations, but to achieve this, the right places are needed. Even though change is ultimately driven by young people, the current responsibility lies with the institutions, which must recognize that the renewal of a country does not depend on private goods but on open spaces and the reduction of bureaucracy. When we stop thinking of space solely as a source of revenue and begin to recognize that the future of a country's economy lies as much in the hands of its young people as in the government that nurtures them, then we will return to creating culture. After all, the lack of culture is born from alienation. And development, by contrast, arises where there is dialogue.

"Spaces are not neutral," says Cecilia Pellizzari, editorial director of Scomodo, who has been working for years to create new ones. "The spaces we want and aim to build are generative spaces, managed and lived in by real communities, capable of offering hundreds of activities and services and truly engaging with the local territory." To confirm this commitment, Scomodo has launched a public shareholding campaign to open five new spaces in five years. "73% of our generation reports feeling lonely, and 87% say that experiences of isolation have a destructive impact on their mental well-being," Pellizzari adds. "For us, spaces are an answer."

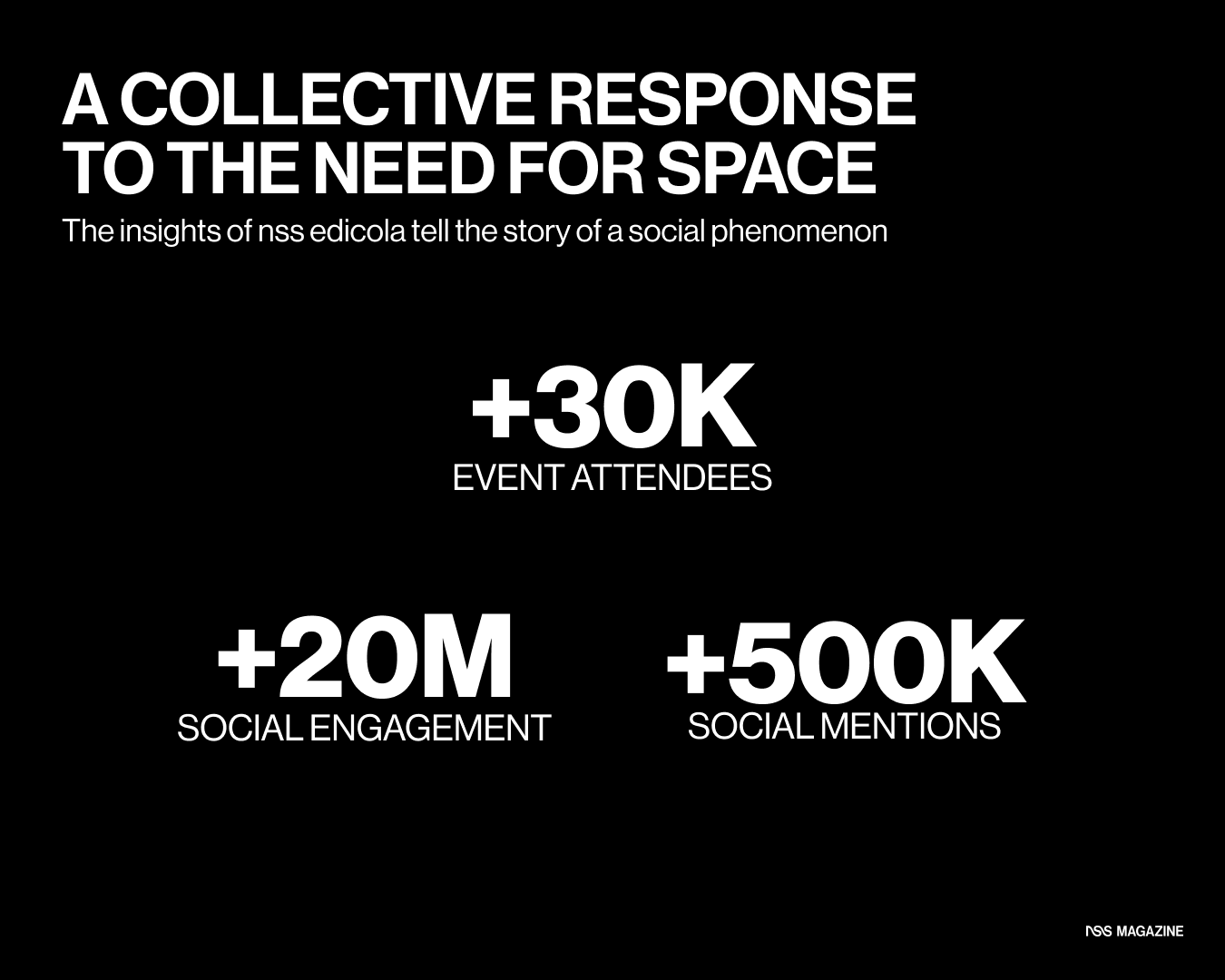

nss edicola as cultural resistance

Third places are emerging all over the world. In Paris, the so-called "tiers-lieux" offer studios, workshops, and exhibition areas to hundreds of creatives who gather under the same roof for different reasons, but who are thus able to meet, exchange ideas, and share knowledge. The association Le 6b, for instance, counts over 200 resident artists and continuously hosts exhibitions, concerts, and other cultural events. Meanwhile, in the United Kingdom, ballrooms are repopulating thanks to the revival of movements like Northern Soul and the creation of dedicated clubs across the country. In Italy, nss edicola was born with the same intent: to bring together new generations, providing them with a space where they can express themselves and explore new perspectives. From a marginalized spot to a crucial hub for local cultural development, the newsstand is capable of amplifying new forms of urban citizenship, telling the story of the present, and shaping the future. At nss edicola, different realities come into dialogue, from information to art, from activism to publishing, all flowing into the vast basin that is the nss community. Every neighborhood that hosts an nss edicola — in Milan, Rome, Naples, and now even in other international cities — rediscovers a vitality that had previously been lost. Since the launch of the permanent newsstands in Milan and Naples, the data collected highlights young people's desire to find a community to belong to: at each event, more than 30,000 people gather around the newsstands in Piazza Buozzi and Piazza San Pasquale, generating a total social engagement of 20 million users and 500,000 mentions of nss edicola's official profiles on Instagram and TikTok. The success of nss edicola in Italy confirms the new generations' strong need to find and belong to such spaces. It demonstrates how a public place, open to the spread of ideas and leisure, can change things not only for a generation but for an entire city. Contributing to urban sociality, collective memory, and material culture is, after all, an act of resistance.