«Entering a bookstore today is a political statement», interview with Saint-Martin Bookshop How to build a cultural physical landmark in the age of brainrot

Even as someone who works in publishing, feeling genuine joy when stepping into a bookshop has become increasingly rare. Not only because Milan has been steadily overtaken by large corporate chains that flatten the act of buying books into a transactional, impersonal gesture, but also because truly independent fashion and art bookshops have almost disappeared. What remains, more often than not, is the editorial corner of the “cool” concept store: industrial interiors, carefully stacked titles, and a selection that feels more decorative than considered.

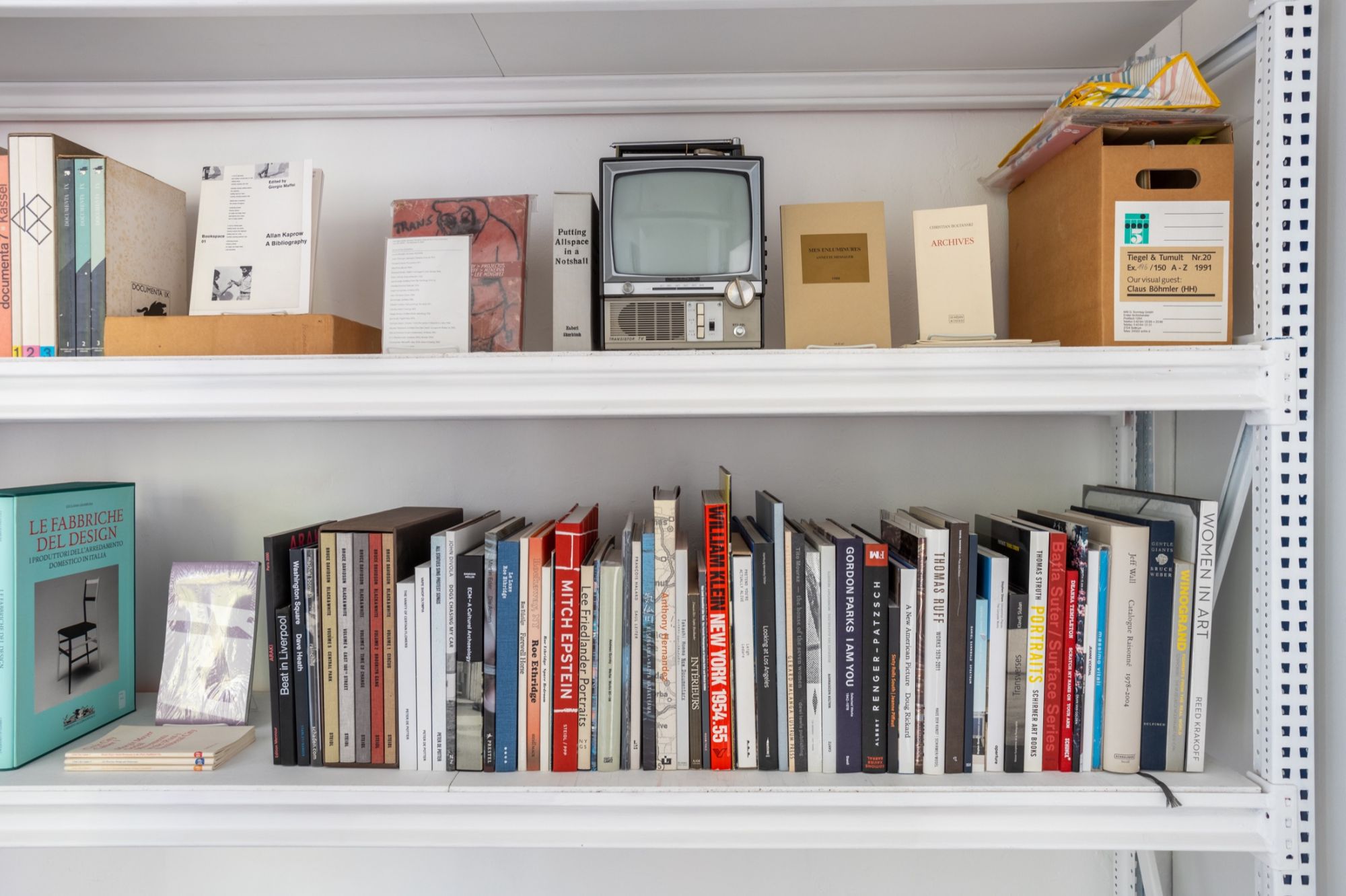

Saint-Martin Bookshop, in Brussels, operates on an entirely different logic. Housed in the former Maison Margiela boutique, it is less a retail space than a lived-in archive, where books are carriers of time and personal taste. Here, selection is an act of authorship, scarcity is intentional, and the bookshop becomes a place of encounter rather than consumption. In an era of brainrot and useless coffee-table books, Saint-Martin stands as a quiet but radical reminder that books can still ask for attention, patience, and commitment. To talk about the importance of cultural third spaces, we interviewed the founder, Stephane Aisinber.

Saint-Martin Bookshop sits at the intersection of art, fashion, and independent publishing. How did the idea come to life, and how has it evolved since the opening?

Before opening the bookshop, I spent years visiting bookshops around the world, and I was often frustrated by how similar they felt. They carried the same books at the same time, because everyone was working with the same distributors. In the end, the only thing that changed was the tote bag. I had wanted to open my own bookshop for a long time, but only if it could exist differently. When the former Maison Margiela boutique in Brussels closed, it felt obvious.

After some renovation work, Saint-Martin Bookshop opened its doors in 2020. In Belgium, during Covid-19, only pharmacies and bookshops were allowed to remain open, and all of a sudden, the entire Brussels art scene ended up gathering at Saint-Martin Bookshop. This quickly positioned the bookshop and allowed me to meet artists, curators, gallerists, collectors, and book lovers.

How does the curatorial process take shape in practice? How do you decide to introduce a new book or a new artist into the space?

At Saint-Martin, the selection is entirely subjective. Sometimes it’s the content that interests me, sometimes the artist, sometimes the object itself. A book can speak through its paper, its design, its silence. I don’t aim to be exhaustive or democratic; the bookshop reflects my taste, my experiences, and my instincts. It’s not neutral, and I think that’s essential.

We focus on working directly with artists and publishers rather than distributors. It’s slower and riskier, but it creates long-term relationships. A good bookshop, to me, is something that becomes meaningful over decades, not seasons. Not to say that selling books today is easy, but many bookshops survive by accepting everything that comes their way, knowing they can return what doesn’t sell. I understand that logic, but it leaves no room for authorship – the bookseller stops creating.

Have there been projects you approached with hesitation, only to see them turn into unexpected successes?

Not really, because when something works here, it usually works elsewhere too. That said, recent launches like the one with Brenda Hashtag for her book brended, or Lara Violetta for the first issue of Violet Papers, brought an incredible number of people, especially very young audiences, and sold out immediately. We’ve also hosted major figures like Gabriel Kuri and Ann Veronica Janssens, alongside emerging artists presenting their first publication. What matters isn’t prestige or scale, but intensity: a project succeeds when the energy is right and when people genuinely connect with the work. Saint-Martin is not about surprises in the commercial sense, but about resonance.

Many contemporary bookshops now operate as hybrid cultural third spaces. How central are events, conversations, and encounters to extending the life of the books you sell?

The catalogue is the backbone of the bookshop, and it’s available online, but the physical space needs to remain alive. Every week or ten days, something happens here: a launch, a signing, a conversation, sometimes simply a drink or music. The goal isn’t primarily to sell books, it’s to gather people, to create encounters, to generate joy. Too many cultural spaces feel intimidating, silent, almost sacred, while in my opinion, a bookshop should be the opposite. When music is playing – even a bit too loudly – and people feel relaxed, they stay longer, they talk, they touch the books. That atmosphere fundamentally changes how books are experienced and enjoyed.

Visitors often become enthusiastic during their visit, compliment me, and tell me it’s the most beautiful bookshop in the world. It’s touching and hard to believe, but I’m happy that it resonates with people. Entering a bookshop today requires courage. Pushing the door is already a political gesture.

What made you commit to Brussels rather than opening this project in cities like Antwerp?

I’m from Brussels, and I have known this building for years. Opening Saint-Martin here felt natural. Brussels allows people to work seriously without being constantly exposed. It’s a city where you can disappear a little, and that’s a luxury for creatives. Meanwhile, Antwerp’s fashion myth belongs largely to another era, the Antwerp 6 are no longer here. Today, Brussels has become a real breeding ground for artists and designers who live here because it’s affordable, discreet, and central: you can have space, raise a family, and still travel easily to Paris, London, or Berlin.

Your selection often includes rare, out-of-print, and limited editions. Do you think cultural objects will continue to be produced in the same way as in the past?

We’re living in a paradoxical moment. The book industry is struggling, bookshops are disappearing, yet more books than ever are being produced. Many of them exist purely as short-term hype. After a few months, they lose all relevance. At the same time, books from 30 or 40 years ago can still feel precise, contemporary, and beautifully made. You sense it immediately in the paper, the design, the content. Good books last. Bad ones disappear. Archives and historical material will only become more important because quality always survives time.

Out of everything you’ve collected, is there a book or object you feel particularly attached to?

I’m deeply attached to the Martin Margiela lookbooks, which I’ve been collecting for years. I still enjoy opening them, touching them, spending time with them. I also love Xerografia by Bruno Munari and The Xerox Book by Seth Siegelaub. I’ve collected several copies of these over time, partly out of passion, partly out of fear of ever being without them. They’re books I return to constantly. They still feel radical, intelligent, and visually strong, and that, to me, is the mark of a lasting cultural object.