The soft masculinity of flower boys From Buddhist principles to aesthetic surgery

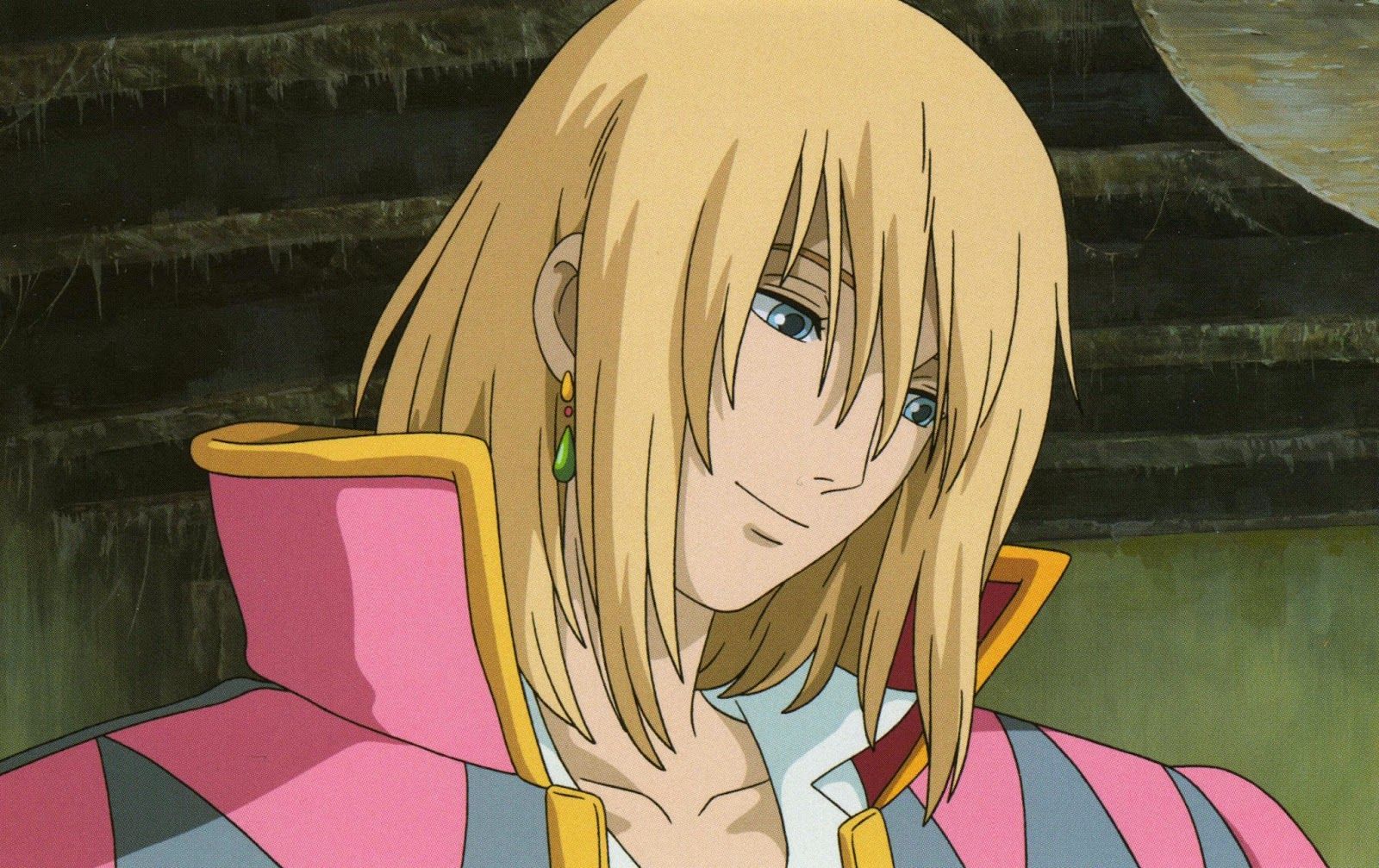

"Flower Boy": not just the title of an album by Tyler, The Creator, but a neologism of South Korean origin that encapsulates an ideological and aesthetic wave that today, after more than twenty years, is also landing among Western trends. A flower boy ('kkonminam') is an appellation used to describe a boy who is 'as beautiful as a flower', young, slim, attractive and attentive to his look, from clothing to skin care, from hairstyle to make-up. Since the mid-2000s, this term has been used to refer to all those K-Pop band members, actors and young idols who prefer a graceful physical presence to the canons of Western male beauty, with prominent jaws and well-defined muscles. Flower boys sport an innocent and androgynous aesthetic that is inspired by that of the bishōnen ('beautiful young men') of Japanese manga and anime for girls ('shōjo'), but without manifesting all those sexual and and androerotic ideals of Japanese pop culture, with roots stretching back to the era of the Chinese Forbidden City.

South Korean history bases its principles in a society centred on the patriarchal figure, with ideologies revolving around hyper-masculinity, male entrepreneurial assertiveness and physical and moral strength. South Korea's strict beauty standards have been established since the Three Kingdoms era when, in line with the principles of Buddhism, the belief that one's outward appearance can affect one's inner soul became established in the population. After World War II, as a result of the military alliance with the United States, American fashion, music and film icons began to depopulate South Korean civilisation, and post-war reconstructive plastic surgery was oriented towards the westernisation of outward features.

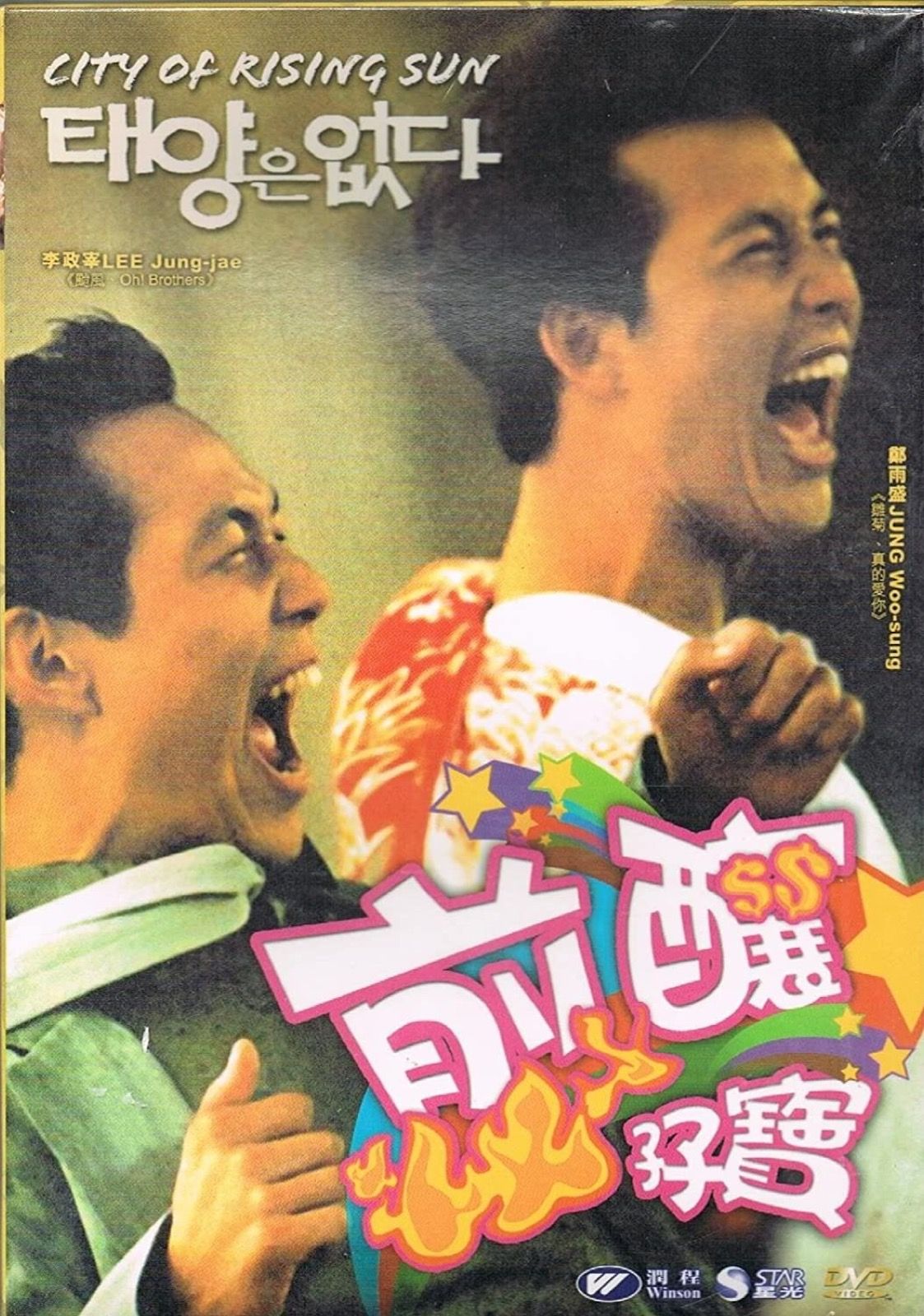

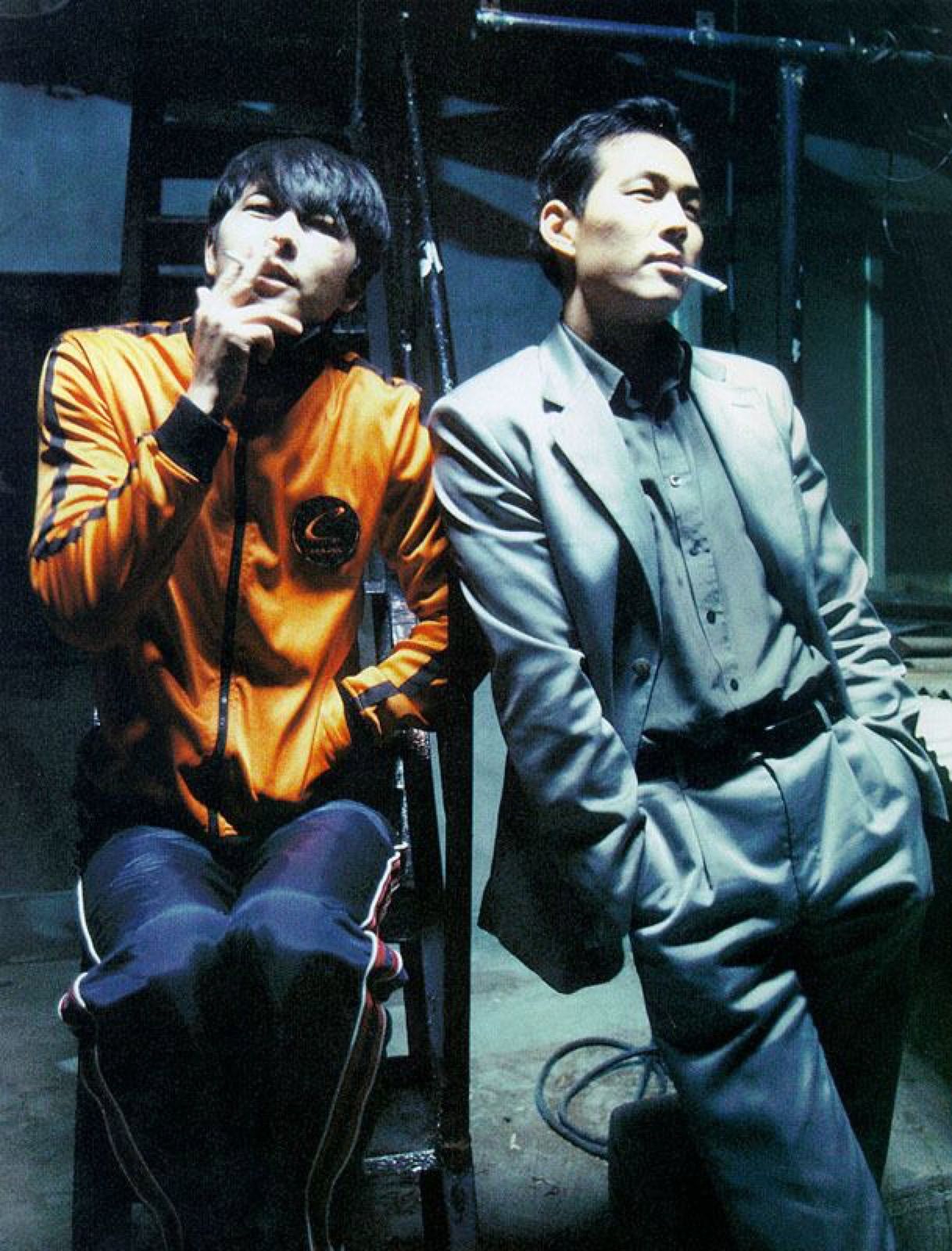

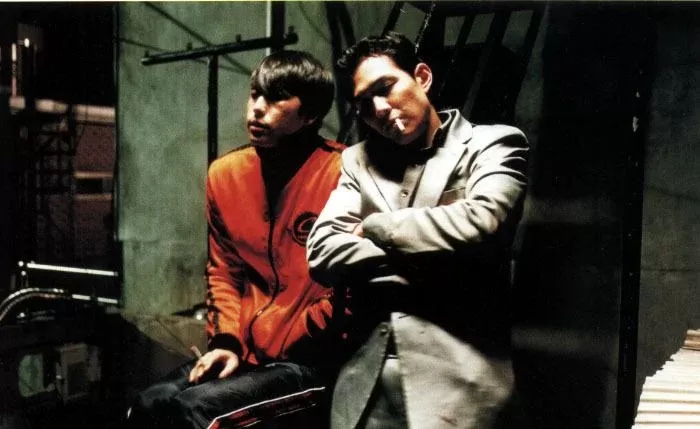

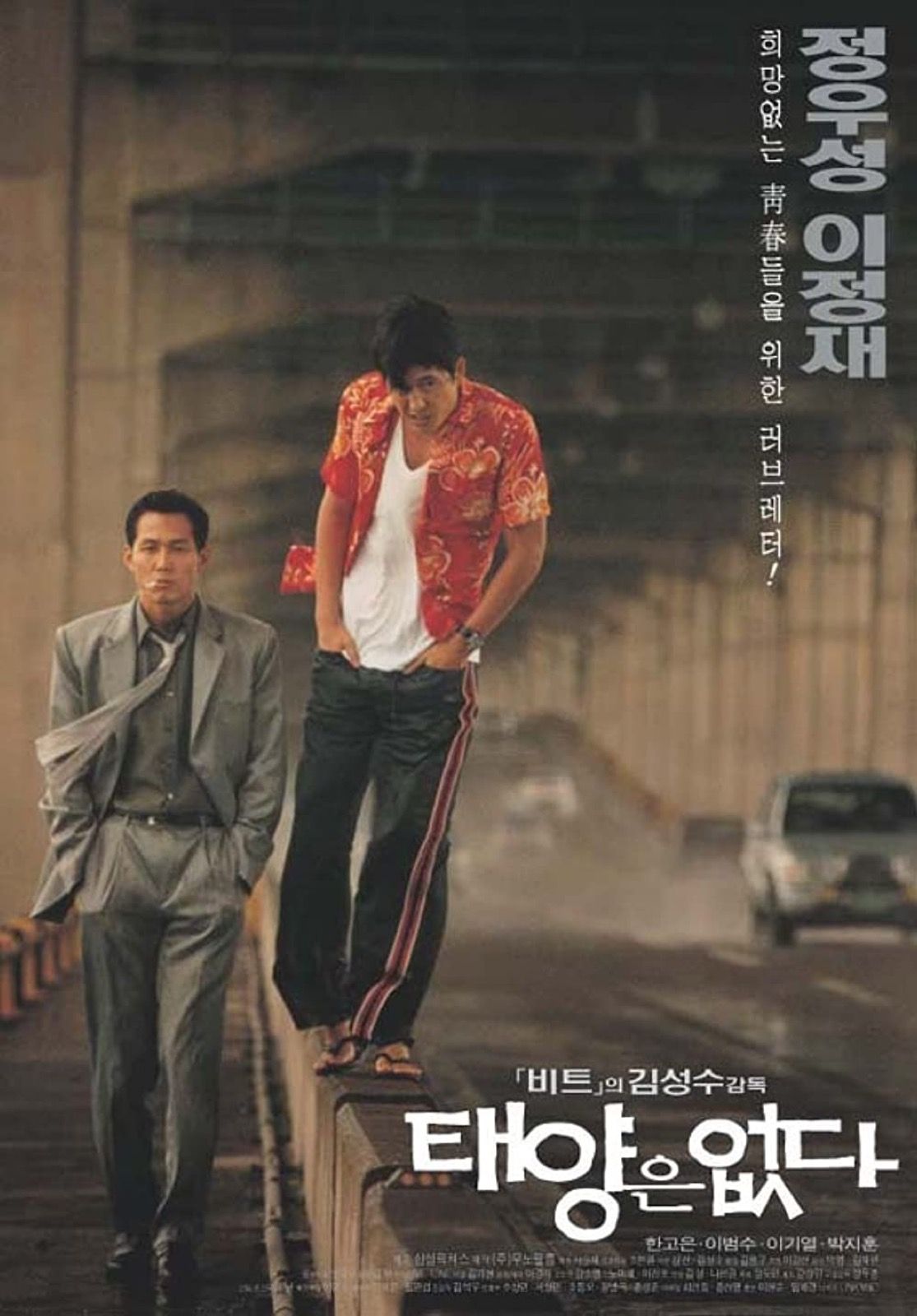

The idea of a 'softer' and gentler masculinity, on the other hand, began to emerge around the end of the 1990s, with the spread of Japanese manga, comics and anime that painted an unprecedented portrait of the modern man: sweet, sincere, passionate and emotional, the comic book boy became the new obsession of South Korean women in no time at all. Tall, with elfin features, fair-skinned and surgically reconstructed double eyelids, the flower boys represent a band of young metrosexuals, the result of the exasperation of bubblegum aesthetics and South Korean prohibitionism, which banned the dissemination of Japanese culture until '98. One film in particular, The City of the Rising Sun, with Lee Jung-jae - the star of Squid Game - among the protagonists, portrays the first glimmers of affirmation of flower boys in South Korea. In skimpy T-shirts and tight tops, fashionable flip flops and brightly printed shirts, two friends during the years of the Asian financial crisis bring to the big screen an avant-garde and effortlessly fashionable style, equal to that which we now espouse in the streetstyle of Seoul Fashion Week. With the introduction of this new male facet, it is no wonder that a large segment of South Korean men are turning their attention to the world of make-up and cosmetic surgery to look as much like all those idols that drive women crazy. South Korea is now the world leader in the production of cosmetics and beauty products aimed at men, a sector that has grown more than 80% in the last five years, thanks to Gen Z and the growing popularity of genderless style. In addition, the Korean Defence Minister recently announced that during military service (compulsory for at least 18 months) a part of the salary will be allocated to the provision of cosmetics and hairstyle products.

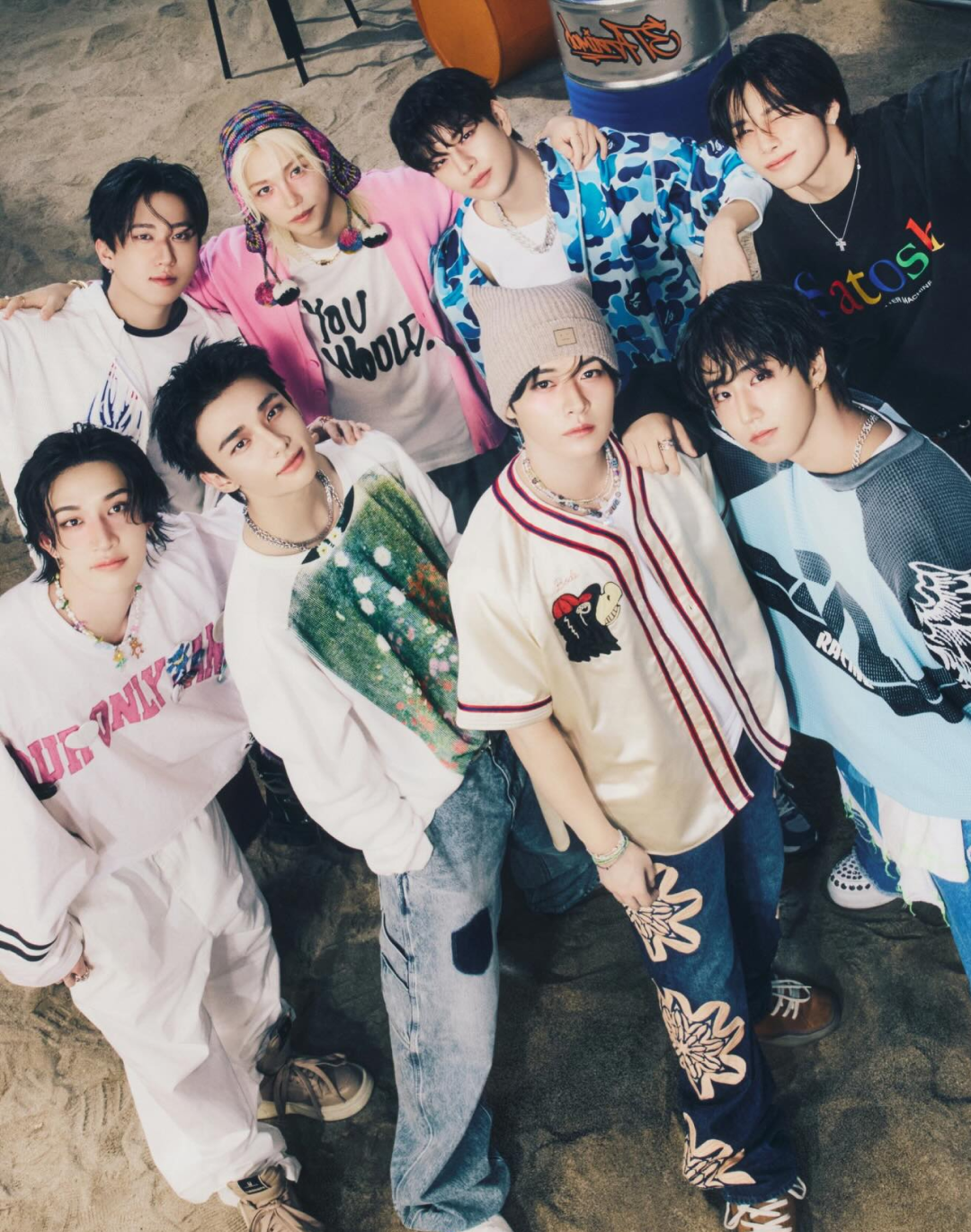

With their well-groomed and friendly looks, BTS, the world-famous K-pop band formed in 2013 in Seoul, to date are stylistic promoters of the Korean popular wave ('hallyu') that has spread globally through the Internet and social media since the 1990s. Together with groups such as SHINee and Big Bang, BTS refer us back to the 'cute-boys-next-door' imagery we previously identified with One Direction and Backstreet Boys, reviving the format of the young and talented boy bands, idolised by young girls but also by mothers. Johnny Suh, member of the South Korean band NCT, was one of the most talked-about celebrities at the Met Gala, with more than 240,000 mentions on social media. With his moonskin and total black silk suit, the K-Pop idol visually represented the evolution of masculinity typical of flower boys, soft and intriguing, with attention to detail.

Diametrically opposed is the situation in China, where the government has recently banned 'effeminate men' ('niang pao', 'female guns') from appearing on television, with a restrictive manoeuvre that, in addition to increasing control over education and culture, forces broadcasters to exclude from broadcasts all those who represent aesthetic currents considered abnormal and immoral, far from the tradition of the Chinese Communist Party. Leader Xi Jinping has launched a veritable derisive hunt for 'sissy pants', a derogatory term for those who deviate from the concept of traditional virility, in favour of a more neutral look. A sharp turn that will have consequences in fashion but above all in the fight for individual freedom, in clear opposition to the new values of fluidity and gender identity. What is currently forbidden in China may be called 'queer' in Italy, but has been a consistent reality in South Korea for decades. More than a trend, it is a common thought that places male aesthetics on the same level as female aesthetics: that of the flower boys is an authentic genderless ideology, of which both men and women promote themselves through an eternal praise of beauty.