When card collecting invented NFTs A model born in the 90s, between new markets and environmental concerns

Throughout the 90s and early 2000s, collecting and exchanging cards was the favorite pastime of a huge number of Millennials, captured by the protagonists of this pop phenomenon such as Magic: The Gathering and Pokémon. Already in the early 2000s, trade magazines and local comic shops fed the circuits of exchanges and collecting the rarest Magic cards - collecting that now, with the digital age, has become more animated than ever. The same happened in the field of Pokèmon card collecting, which turned into a turnover so large that it even attracted scammers like those who sold Logan Paul 3.5 million dollars in fake cards. The card collecting model has numerous similarities with that of NFT in which, in fact, the Hasbro company, owner of the Magic: The Gathering brand, has recently begun to develop, as stated by CEO Brian Goldner last April. The development, to tell the truth, was already happening by itself: two weeks ago Wizards of the Coast, owner of the game, sent a cease-and-desist letter to the @mtgDAO community who wanted to use the pre-existing Magic cards to create their own NFT ecosystem, not unlike how Mason Rothschild was hit by a cease-and-desist of Hermès after putting his MetaBirkins on sale.

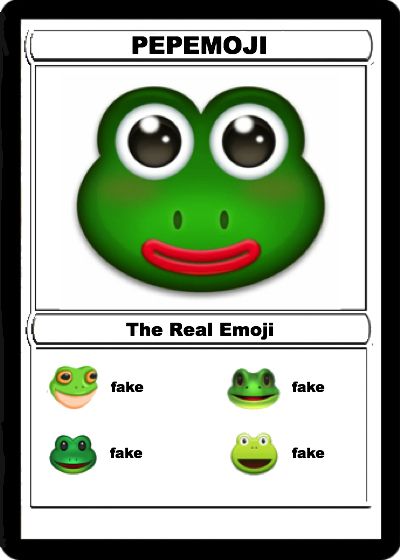

The relationship between Magic: The Gathering and NFT, however, runs far back in time. At the time of 4Chan, one of the first OG memes, Pepe the Frog, became the protagonist of a meta-ironic joke: online users took the stock photo of the character, modified it by inserting it into a new context and called it Rare Pepe. The game went so far that in 2018, developer Joe Looney founded Rare Pepe Wallet, the first online marketplace dedicated to a meme and based on the blockchain. Its only antecedent is the online game Spells of Genesis, which used the blockchain to make its users exchange digital cards. Pepe The Frog's images were bought and exchanged exactly like collectible cards (some had the same format as Magic: The Gathering cards), authenticated via the blockchain and also sold at exorbitant prices: the record was broken for the first time in 2018 when at the Rare Art Digital Festival a Pepe the Frog with the appearance of Homer Simpson was sold for $ 38,500. Later, the buyer, Peter Kell, resold it as NFT last March for $321,440. With Rare Pepe Wallett we can perhaps talk about the first real online meme marketplace – a space dedicated to a small circle of enthusiasts and collectors but which demonstrates beyond any doubt how blockchain technology, applied for the first time to art in 2014 (the quantum timestamp, the first NFT ever created reads "05-03-2014 09:27:34"), was developing.

Today, instead of Pepe the Frog, there is the possibly problematic Bored Ape Yacht Club – which, however, has the exact same mechanism as the Rare Pepe Wallet which, in turn, even imitated Magic: The Gathering in the graphic set-up. In the world of collectible cards, in fact, a reality that combines fantasy history, collectible cards and NFT already exists and is called Cross the Ages – a sort of gaming multiverse that is gaining enormous traction, with a partnership already close with The Sandbox before the launch, 192,000 followers on Instagram, and the release of a novel (also a format borrowed from Magic: The Gathering). Both Wizards of the Coast and Nintendo, in the case of Pokèmon cards, have expressed a cautious interest in the field of NFT that the CEO of Hasbro has defined as «a real opportunity» considered as Hasbro, in addition to Magic, also owns franchises such as Transformers or G.I. Joe. It is clear that the decision to bring a world together so far and so close to the NFT has worried the fan base of card collectors, some of whom have spent the last twenty years building high-value collections and who do not want to see their territories invaded by crypto-bros. Concern that however clashes with the enormous market value achieved by the digital versions of Magic: according to analyst Milton Griepp in February last year half of the operating profit of the Digital Gaming segment of Wizard of the Coast amounted to 420.4 million dollars – 46% of that of the whole company.

It is clear that expanding this segment in the NFT market could grow this already very high number, and yet, beyond the grievances of the original gaming community and the brand equity issue, which is of little importance from the corporate point of view of the story, the most serious concern raised across the board by the community of fans of the game concerns, oddly enough, sustainability. Joshua Nelson of Bleeding Cool posed the question as clearly as possible:

«Anyone who knows about NFTs knows that the crypto-art is bad [..] for the environment. But the thing to consider is that Magic: The Gathering is also quite bad for the environment as a whole. Every year, Wizards of the Coast prints four premier sets and all manner of supplemental products. […] There has also been an initiative for Wizards to push for a cleaner footprint, so obviously if Hasbro wants this for the game, something will have to give. Will that be paper Magic, or the NFT opportunity? […] If NFTs are less impactful against the environment than printing paper cards, perhaps they should fully commit to Arena and forgo printing Magic: The Gathering cards altogether. But if paper Magic is less impactful, they should turn away from creating any amount of NFTs completely».

The accessibility dilemma that sees the opinion of fans divided also applies to the issue: the proposed model of @mgtDAO was based on «a format where you could only play the cards you own the NFT for, which is an idiotic idea that means only the richest players get to play with what would be a staple in other formats», as Joe Parlock of The Gamer writes that the introduction of NFT in the game could represent its end. According to others, however, it is quite the opposite: with platforms such as Coinbase or Collectable that allow you to manage the sale and storage of collections, but also to buy individual shares of a certain card, NFTs are hyper-accessible as they allow anyone to participate in collecting regardless of their geographical location. Bringing new generations and communities into collecting would create more demand and thus increase the overall value of the market, but above all each sale of NFT would result in a gain for the original artist since NFTs work like royalties. As for the game, everything would move to the digital plane, in a way not too different from how it is now. Ultimately, then, the conflict of this story lies in its values: should we preserve the original values of the game and its fundamentally democratic and open community or let corporate interests lead their intellectual property towards a path that could distort it?