The season of fashion revivals In Milan and Paris the big names of fashion of the past are returning

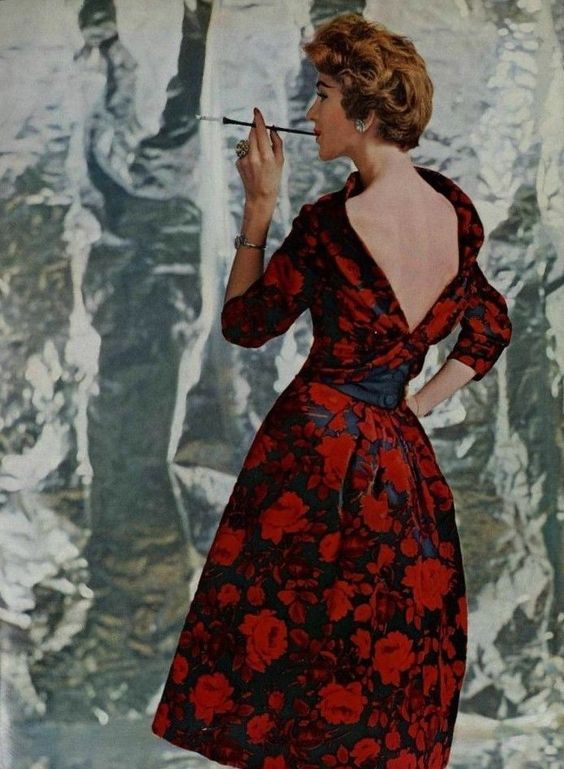

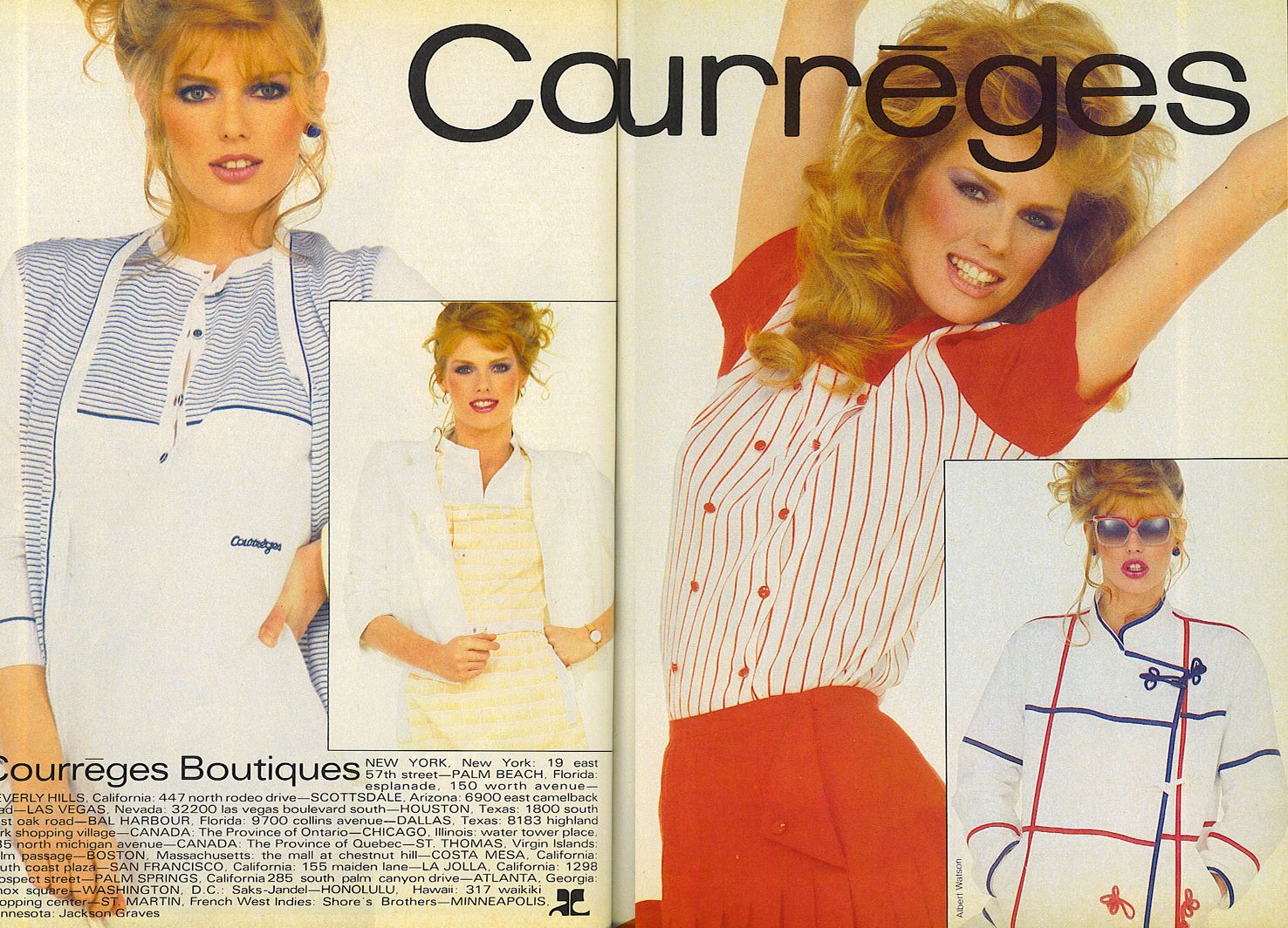

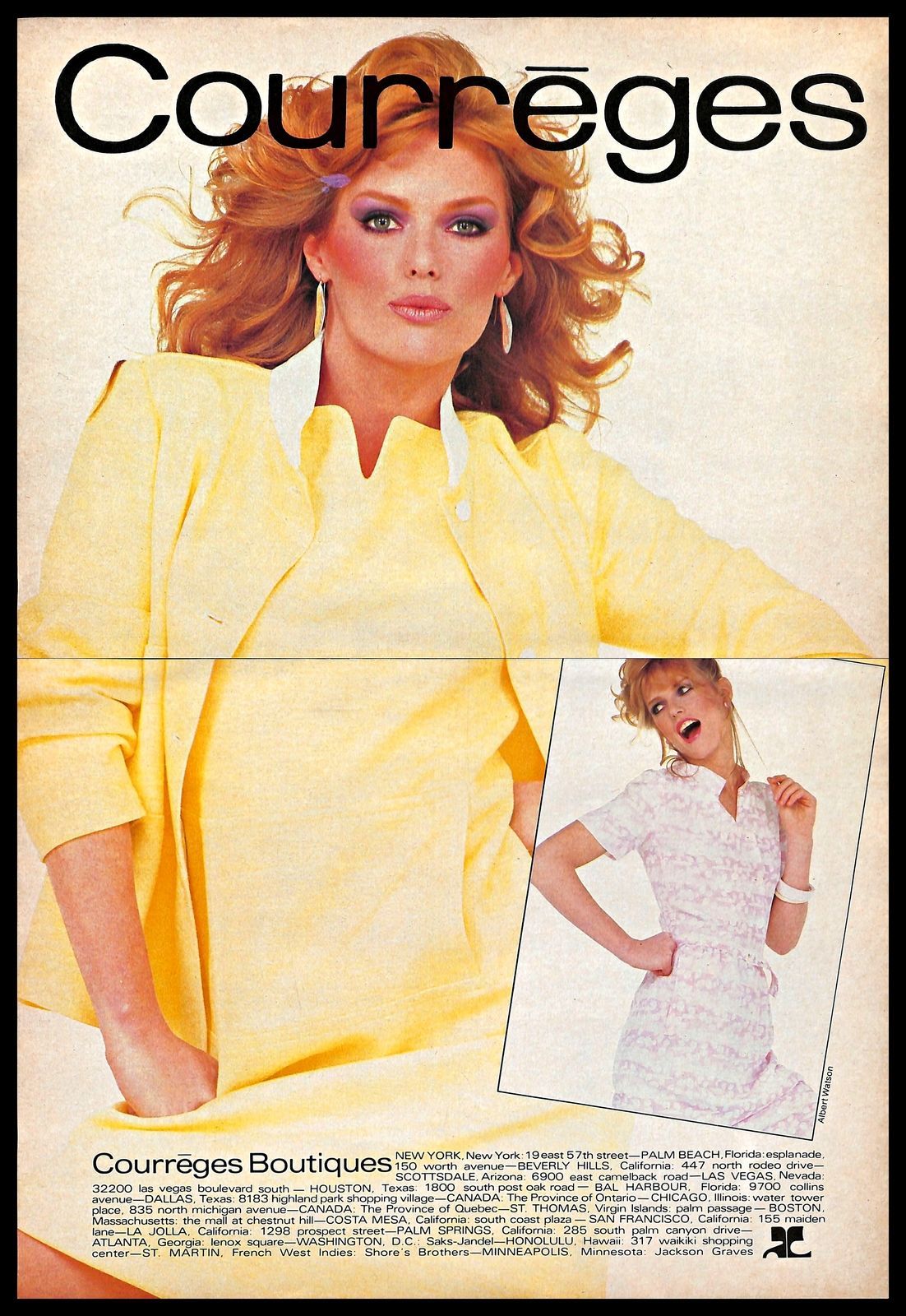

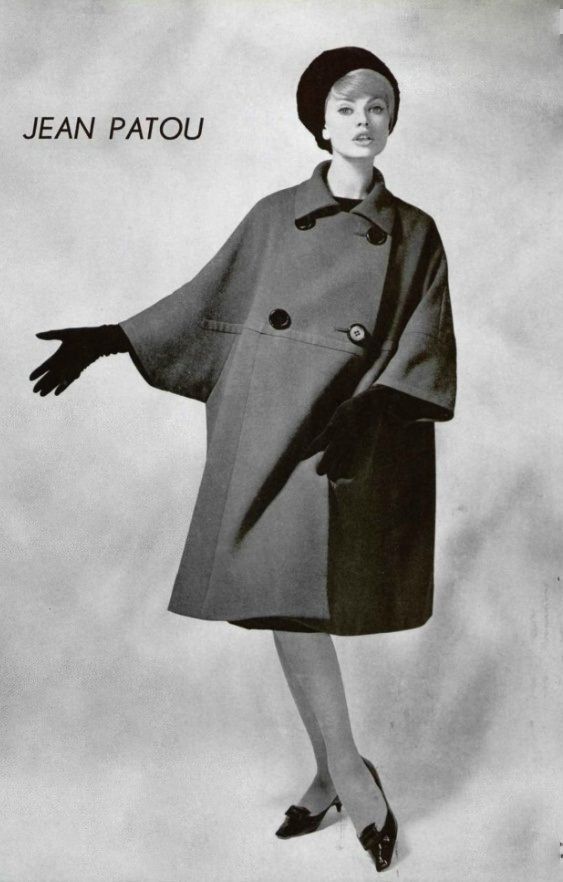

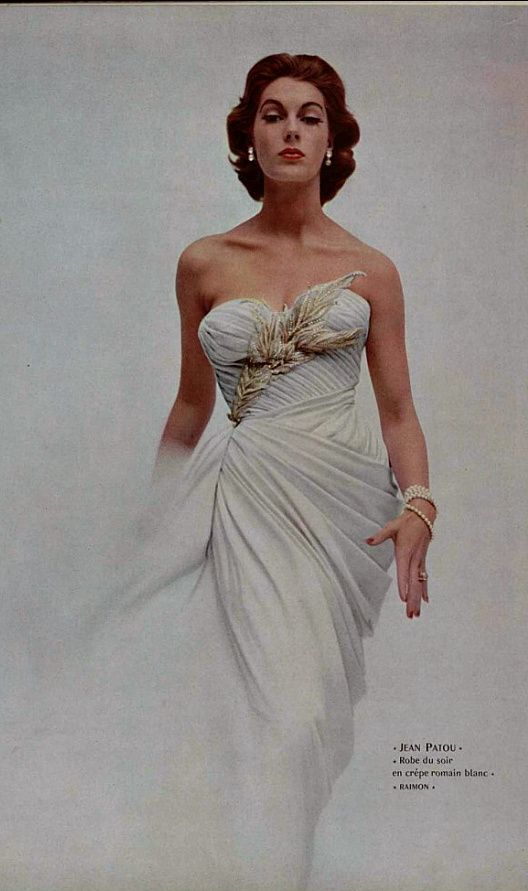

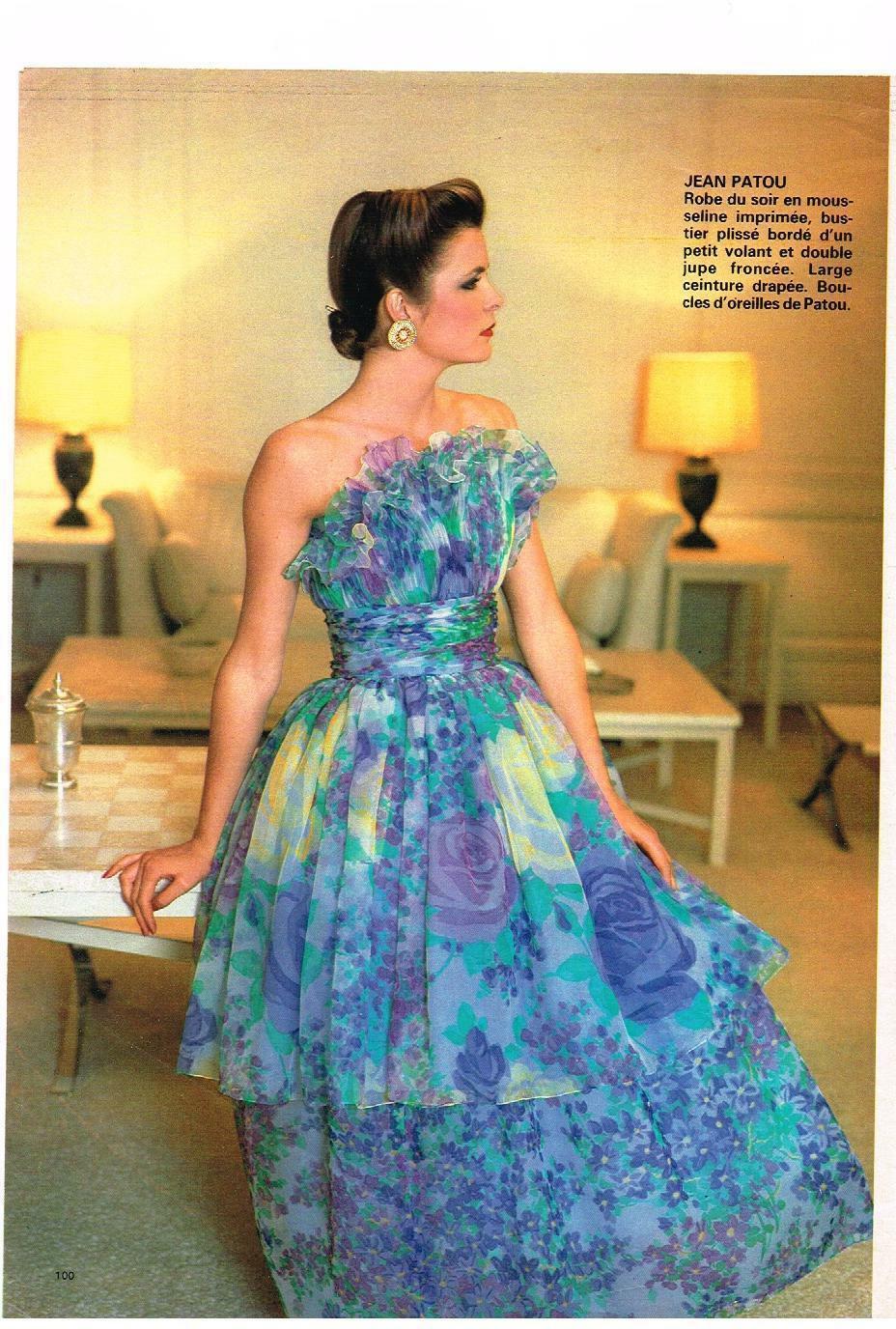

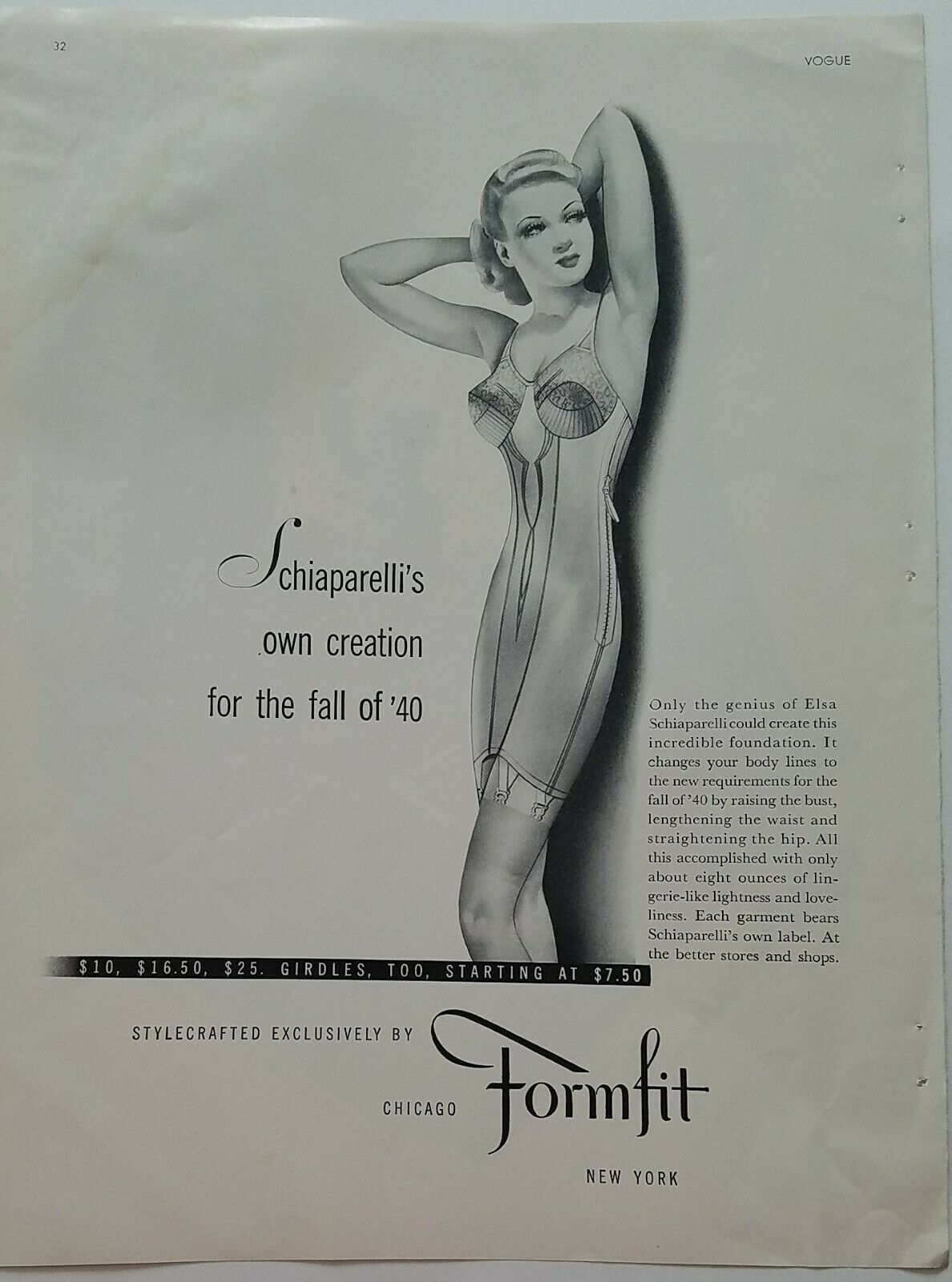

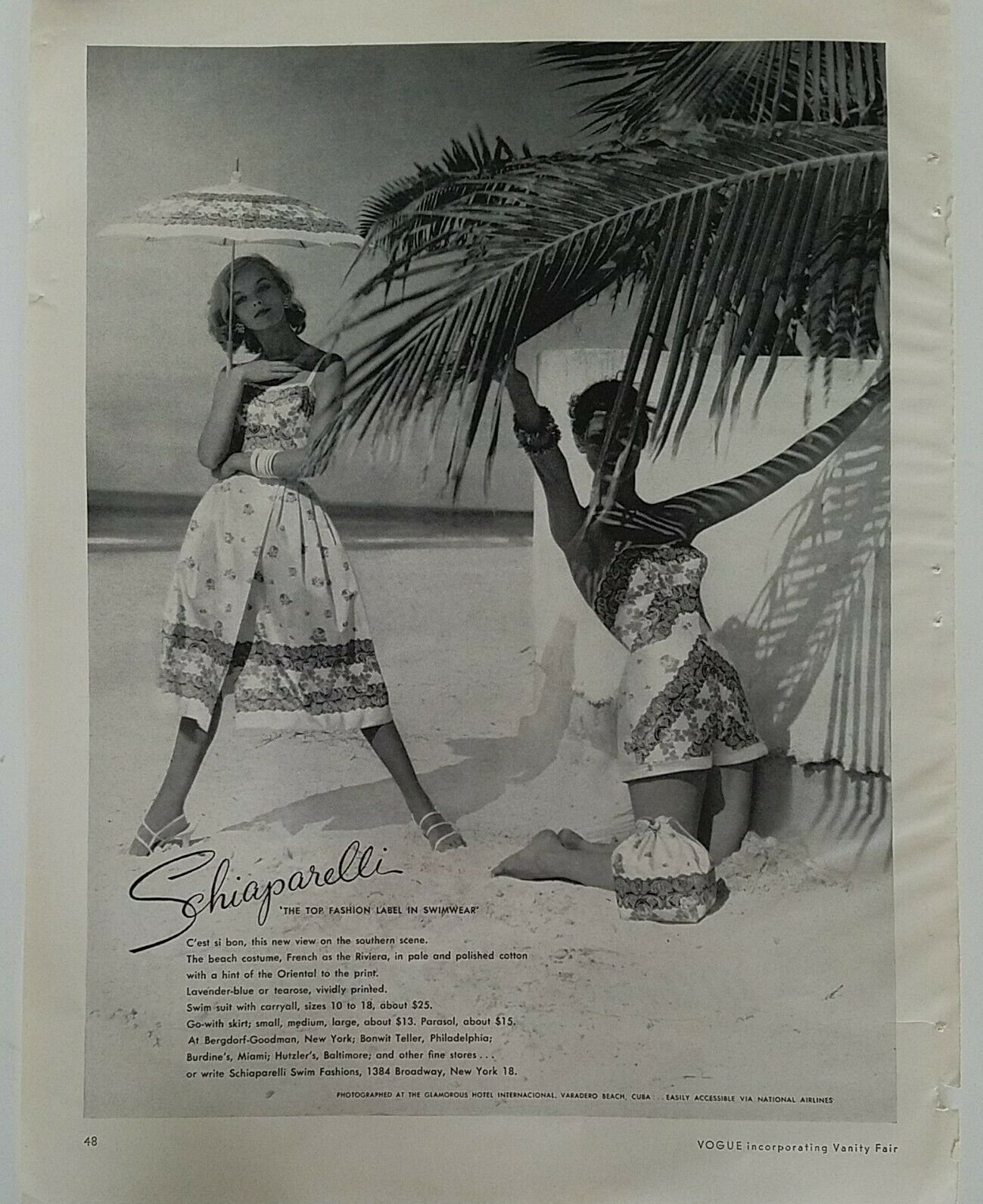

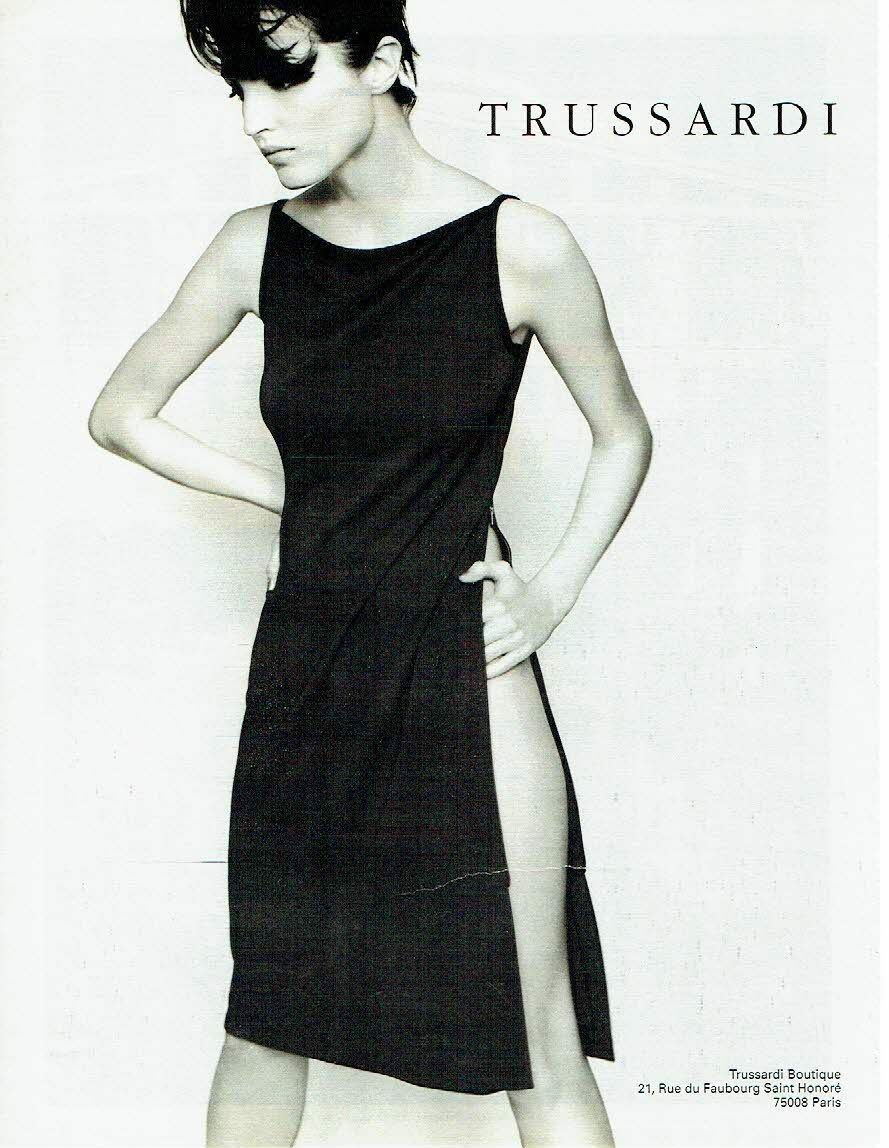

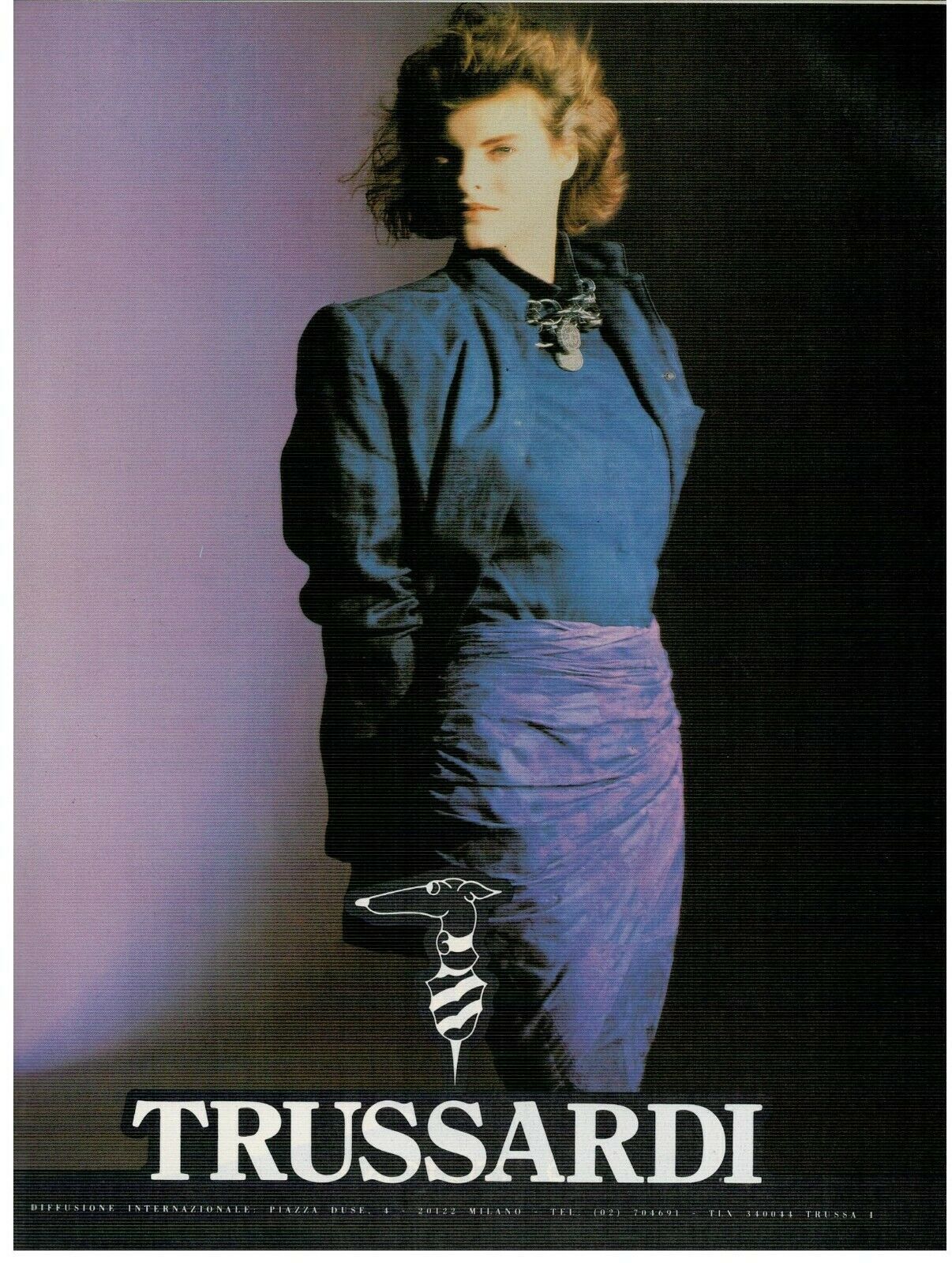

The history of fashion is a story of courses and recourses – and just as fashion trends come and go, the big fashion brands also live strange lives. Leafing through an old edition of Vogue, let's say from the 80s, the modern reader could be faced with names of big brands that, today, do not enjoy the same notoriety. Precisely those brands, however, this year have returned or are about to return: if in France this season of great revivals began during the pandemic and will reach full speed with the next fashion week, in Italy too the houses of the past are rediscovering the archives and finding new and young creative directors who bring them in step with the present. Without a doubt, one of the most anticipated revivals of February is that of Trussardi, a century-old brand that in the 80s was brought into vogue by Nicola Trussardi and that maintained its success over the years while diluting its strength in the thousand streams of its diffusion lines; another great return announced in recent days is that of Balestra, a couture maison in Rome that in the 60s dressed the jet-set and the royal houses of half the world but then gradually disappeared against the background of an industry that never stands still. The same, in recent years, has happened with Patou and Courregés in Paris following the imprinting of Daniel Rosenberry from Schiapparelli, whose real rebirth began only in 2019.

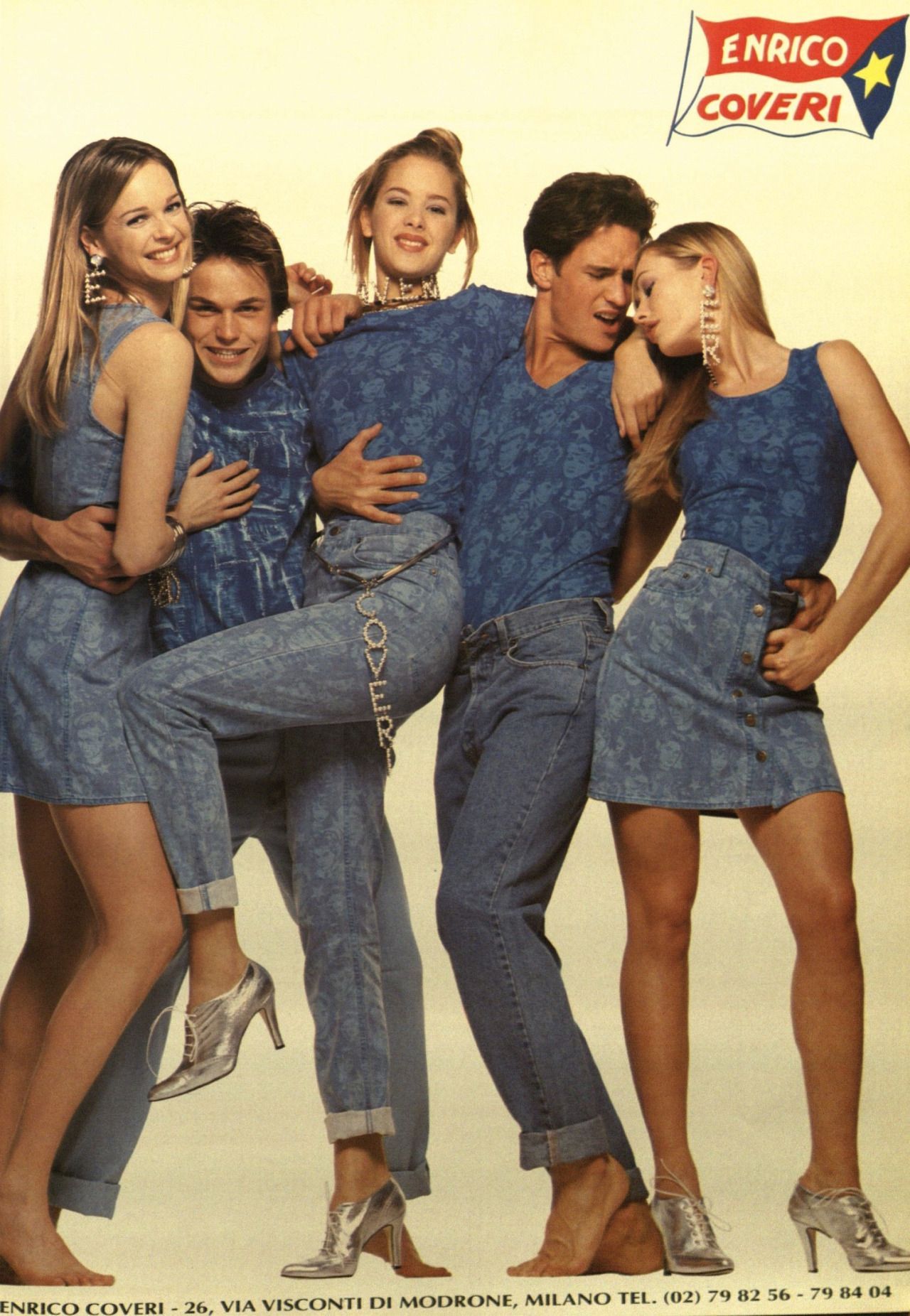

The fashion industry has its own way of decreeing the life or death of a brand. The death of a brand, apparent or not, is often a sort of "civil death": brands remain alive but, after years, and often due to the policy of wild licensing of the 80s and 90s, their products slide further and further down the retail pyramid. Pierre Cardin, Angelo Litrico and Enrico Coveri are all examples of historic mid-century fashion brands that are known to Millennials for products that are far removed from their actual legacy or their righteous place in the history of fashion – the fault of licensing but also of a difficult adaptation to the new settings of the fashion industry. Something similar had also happened to Halston, a technically alive brand that reappeared in the headlines only after the success of the Netflix series of the same name. Patou, Courregés, Trussardi and Balestra also based their revival on the arrival of a new guard and it is no coincidence that these revivals took place riding the wave of social responsibility and new and contemporary creative direction – a periphrasis to indicate the arrival of new and exciting designers at the helm of brands that have disappeared from the catwalks years ago.

This revival has often and willingly taken place within a larger industrial superstructure: Patou had the almighty LVMH group behind it, Courrèges had the Artemis group which is owned by the Pinaults of Kering, Trussardi had the QuattroR fund. Balestra, who will participate in Milan Fashion Week on February 24th, is instead basing its reloading on his own strength – something that makes sense considering how its atelier has never really stopped, signing looks seen on the red carpet of the last Venice Film Festival. In general, however, it can be said that, based on the example of Schiapparelli but also on the first steps of Patou and Courregés, in recent years both CEOs and fashion creatives have discovered that the great fashion houses of the past are actually excellent spaces for construction and reconstruction precisely because of the oblivion into which they have fallen.

The name of these commercial giants of the past still retains its ancient prestige and therefore still hides great commercial opportunities, as well as great possibilities for their creative directors to operate in a sort of safe zone, achieving great success in most cases: Daniel Rosenberry, Nicolas Di Felice, Guillame Henry have found fame and fortune becoming the protagonists of the revivals of the brands they lead – and fashion bookmakers predict that the same will happen to Serhat Işık and Benjamin A. Huseby with Trussardi, given the growing success of GmbH since its debut in 2017. The most interesting part of the whole process is that the format of the revival of a historic brand is a sort of win win for which, on the one hand, new creatives are given the opportunity to make their voices heard and, on the other, it prevents the heritage built in years of hard work by the founders of those same brands from being wasted in neglect, thus ensuring a sense of continuity to all parts of the fashion industry.