What does menswear say about our culture? A chat with Jacob Gallagher, WSJ fashion editor and author of "The Men's Fashion Book"

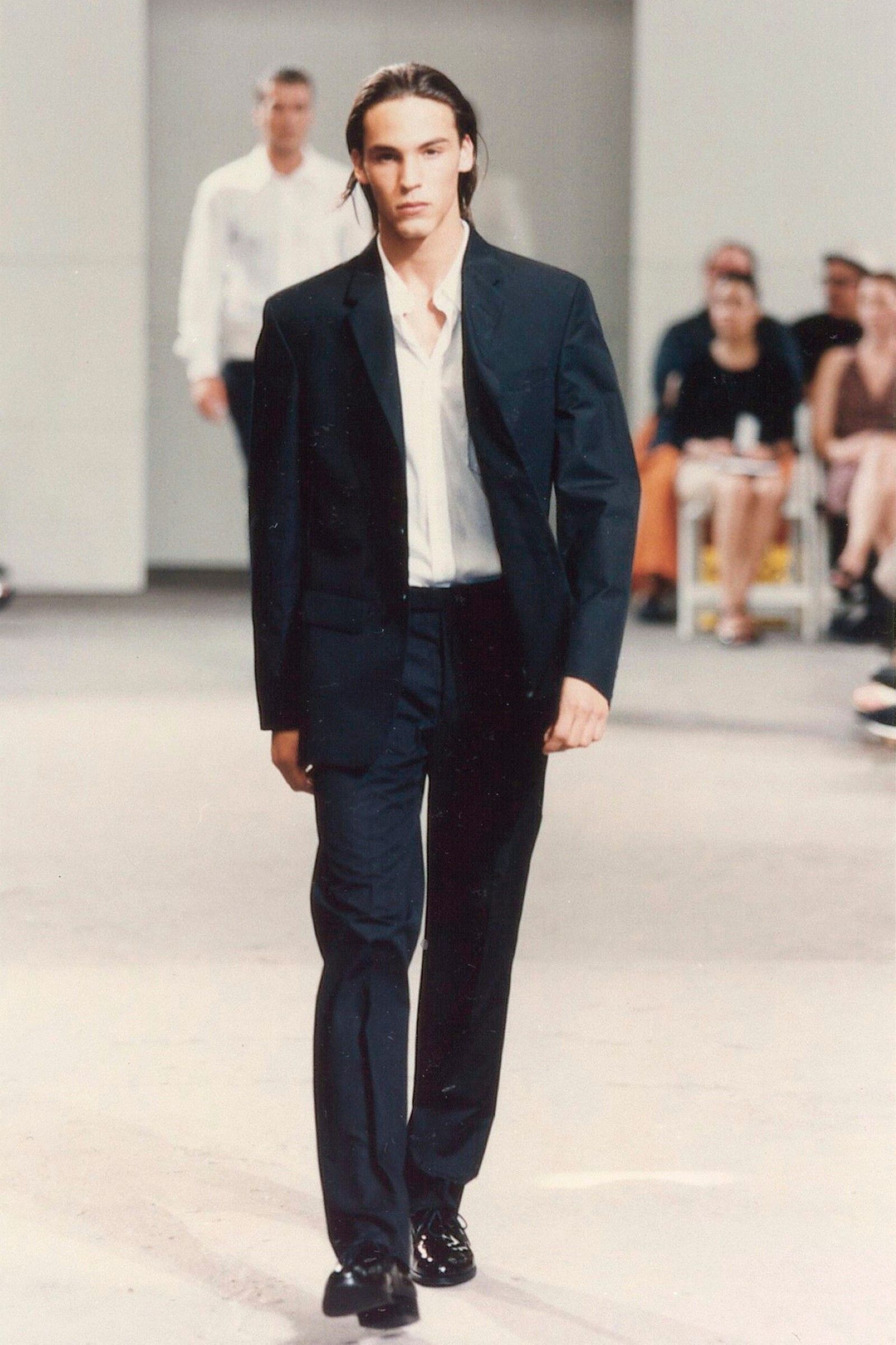

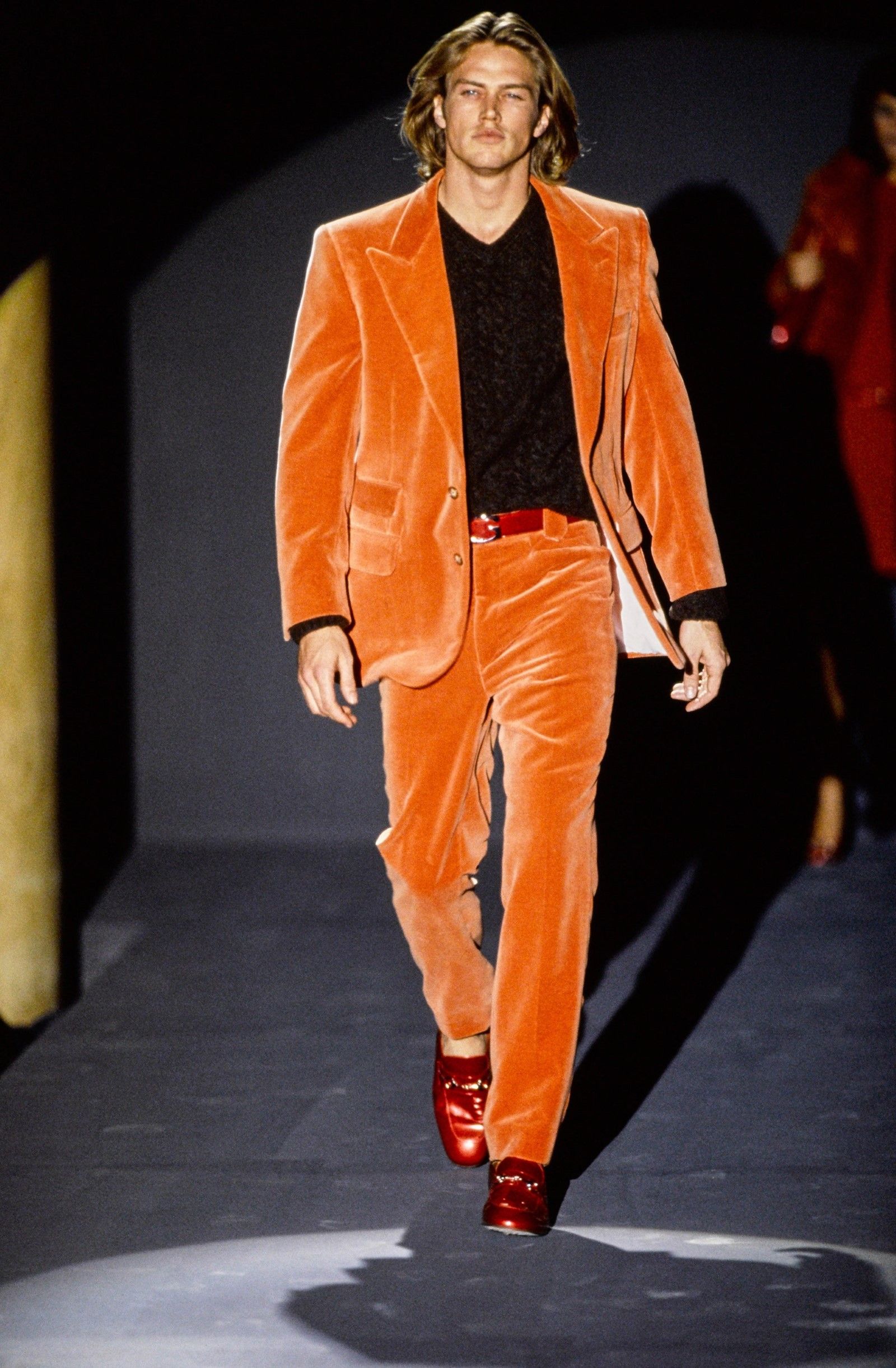

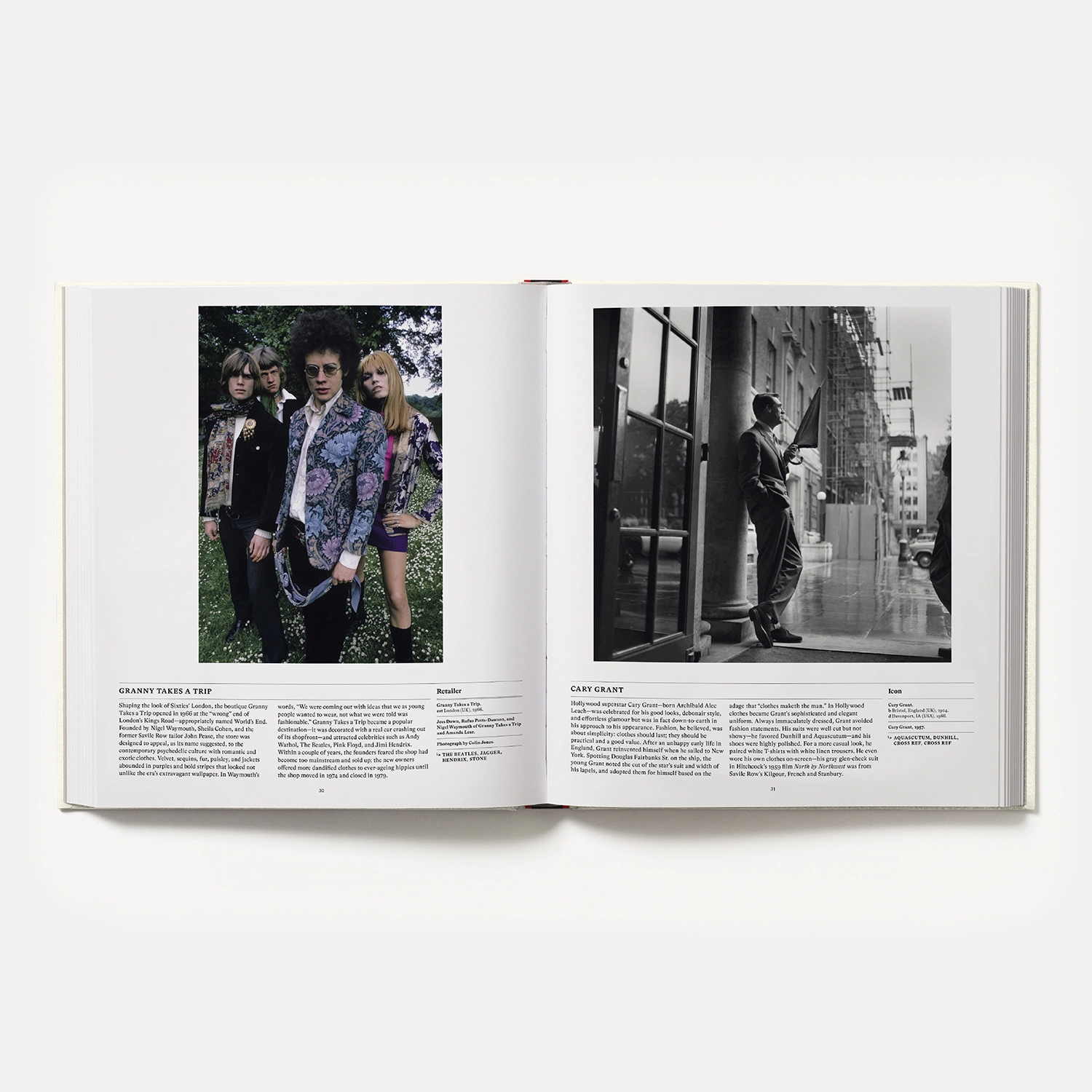

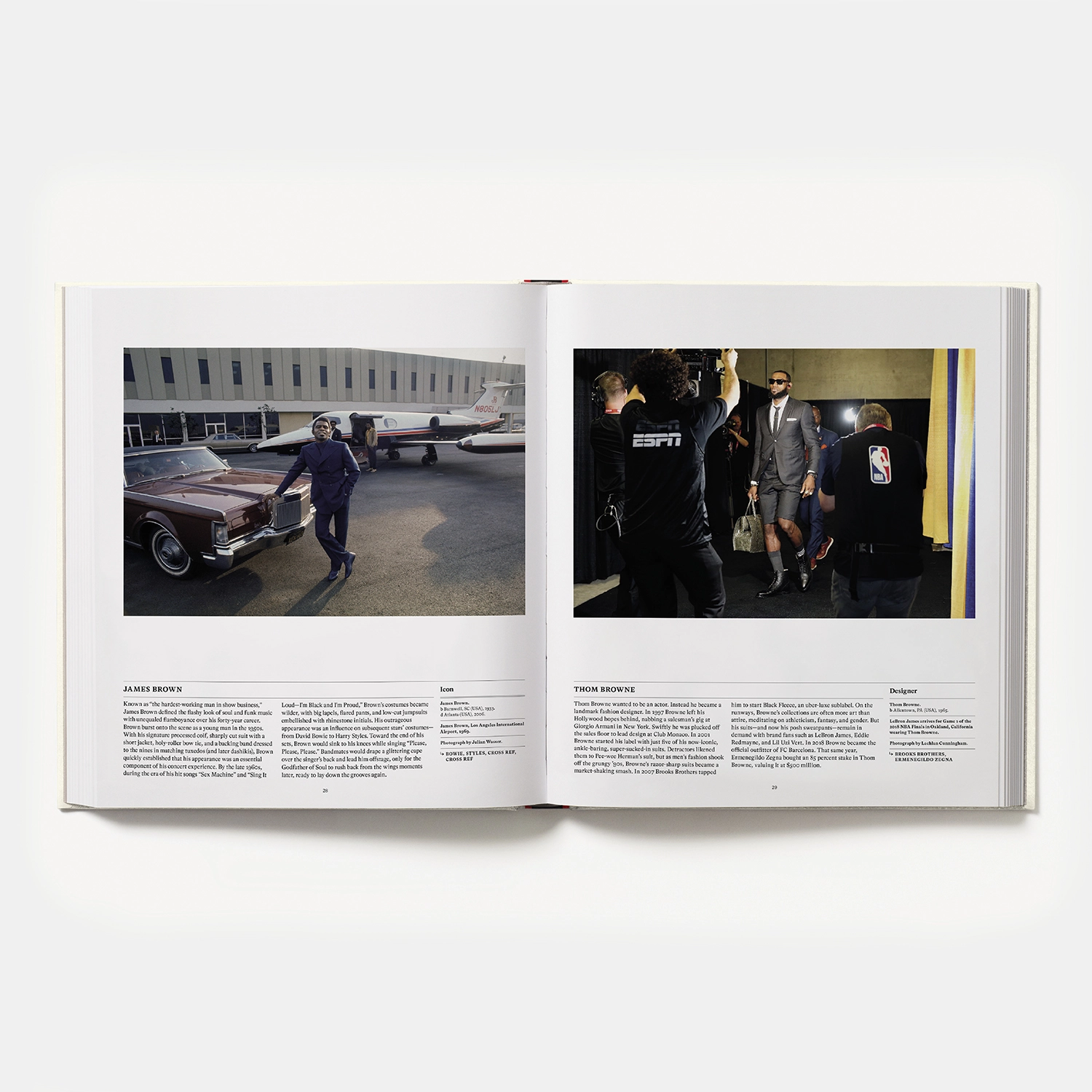

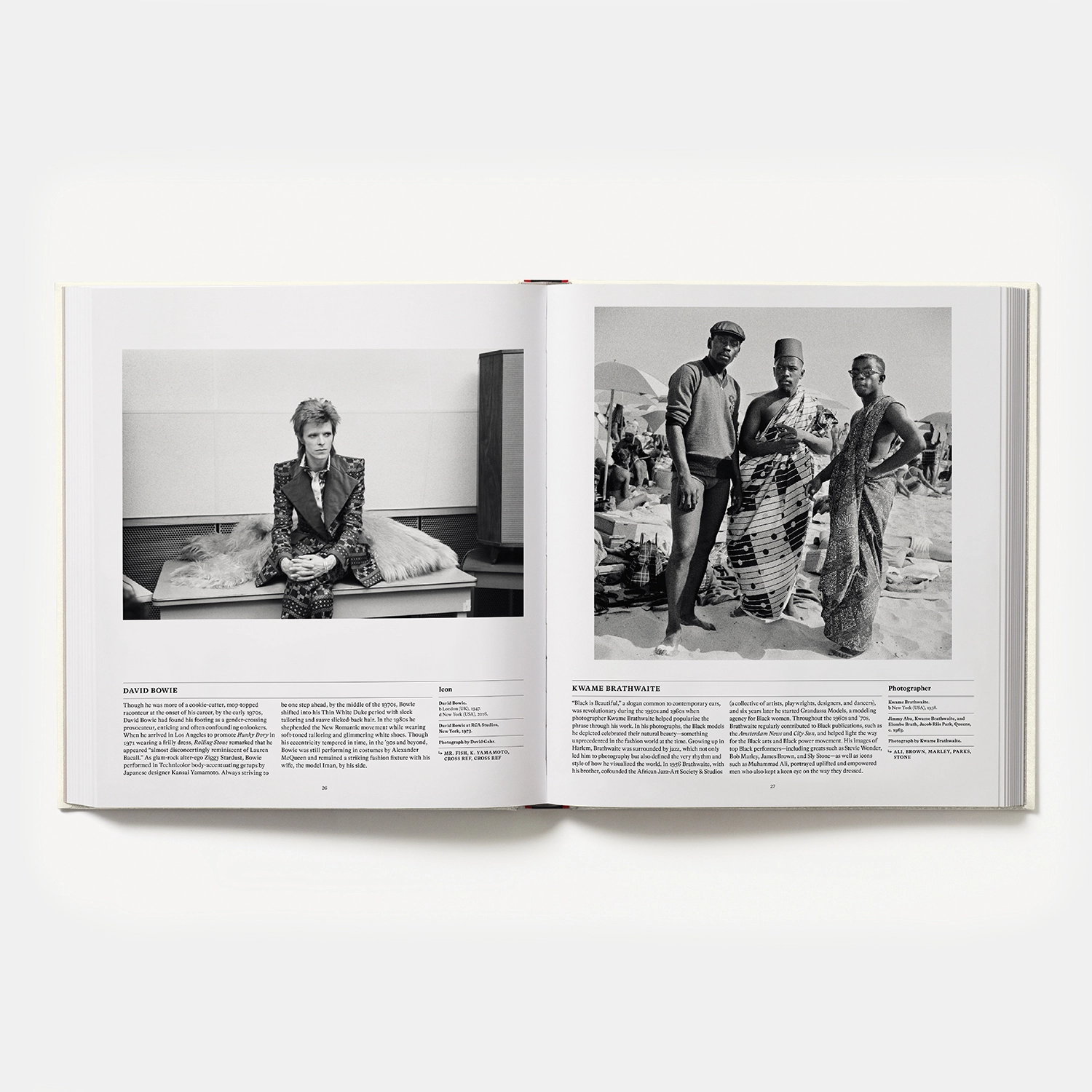

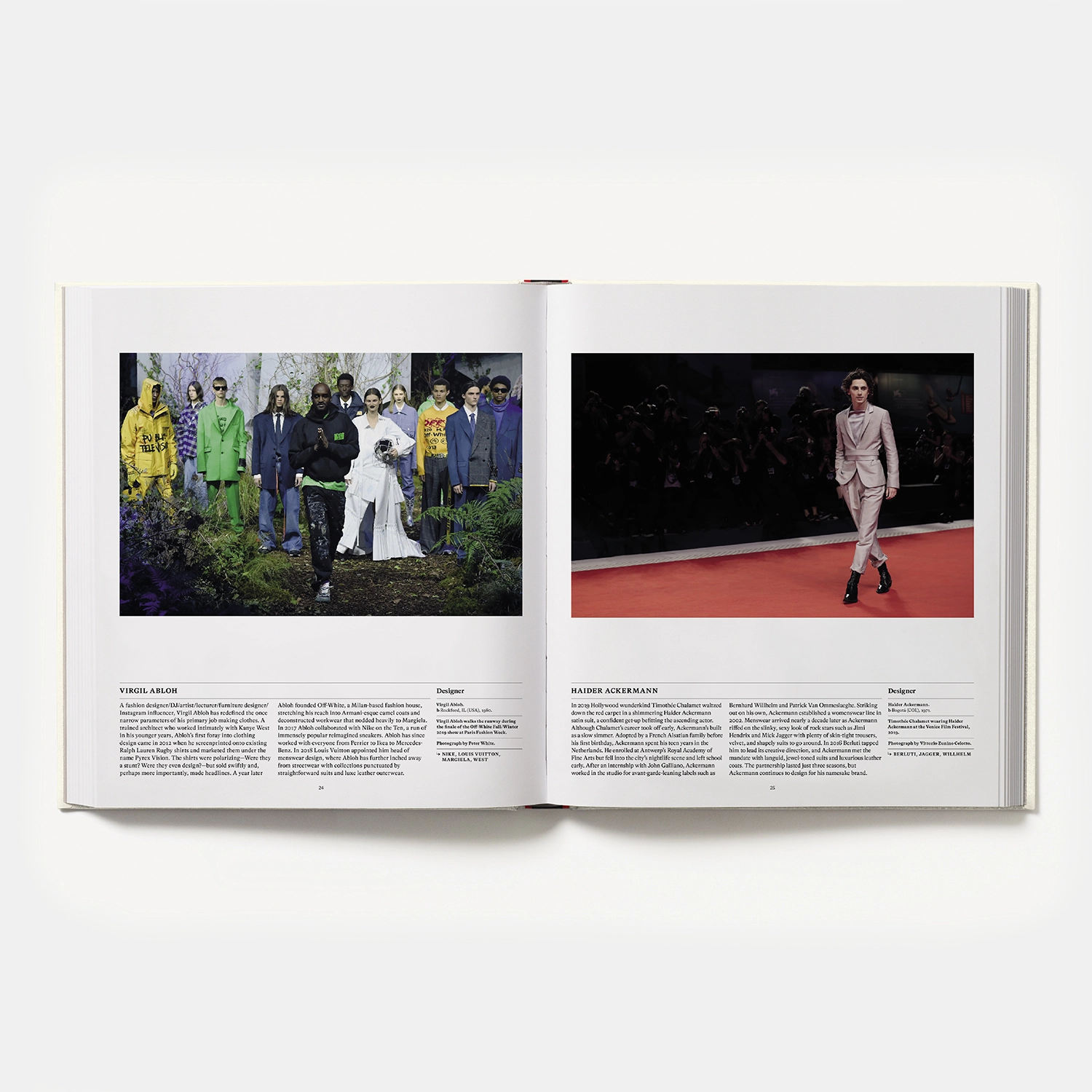

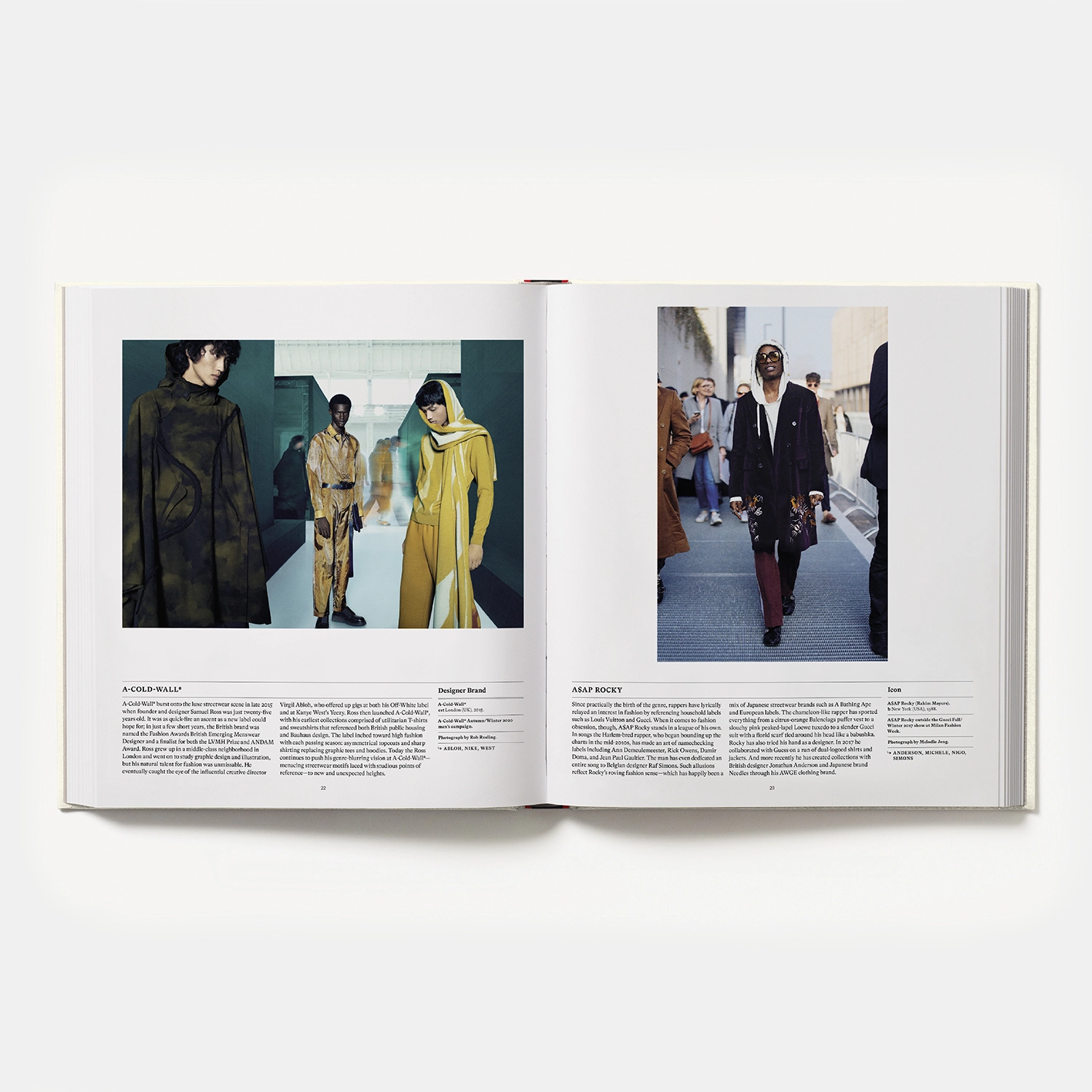

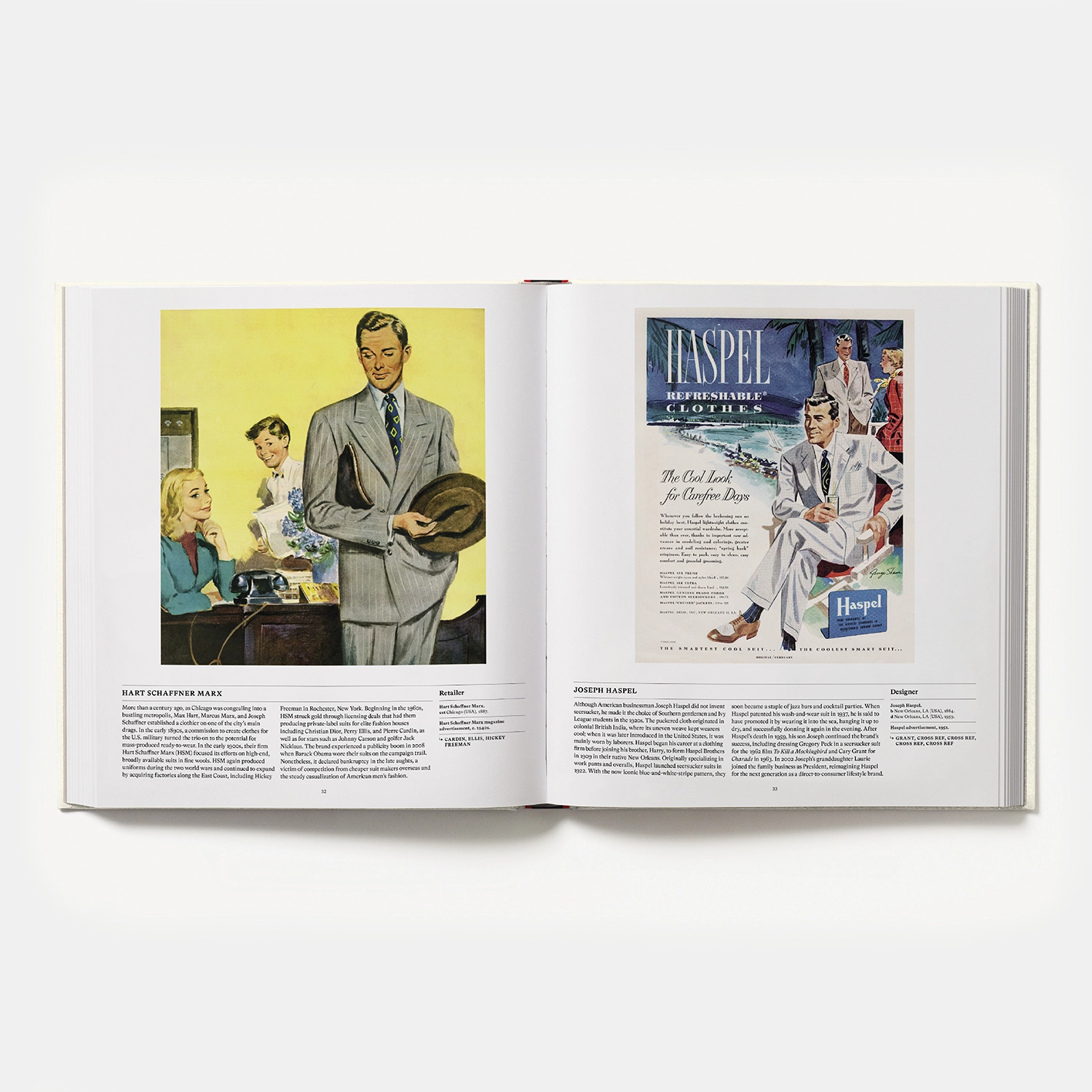

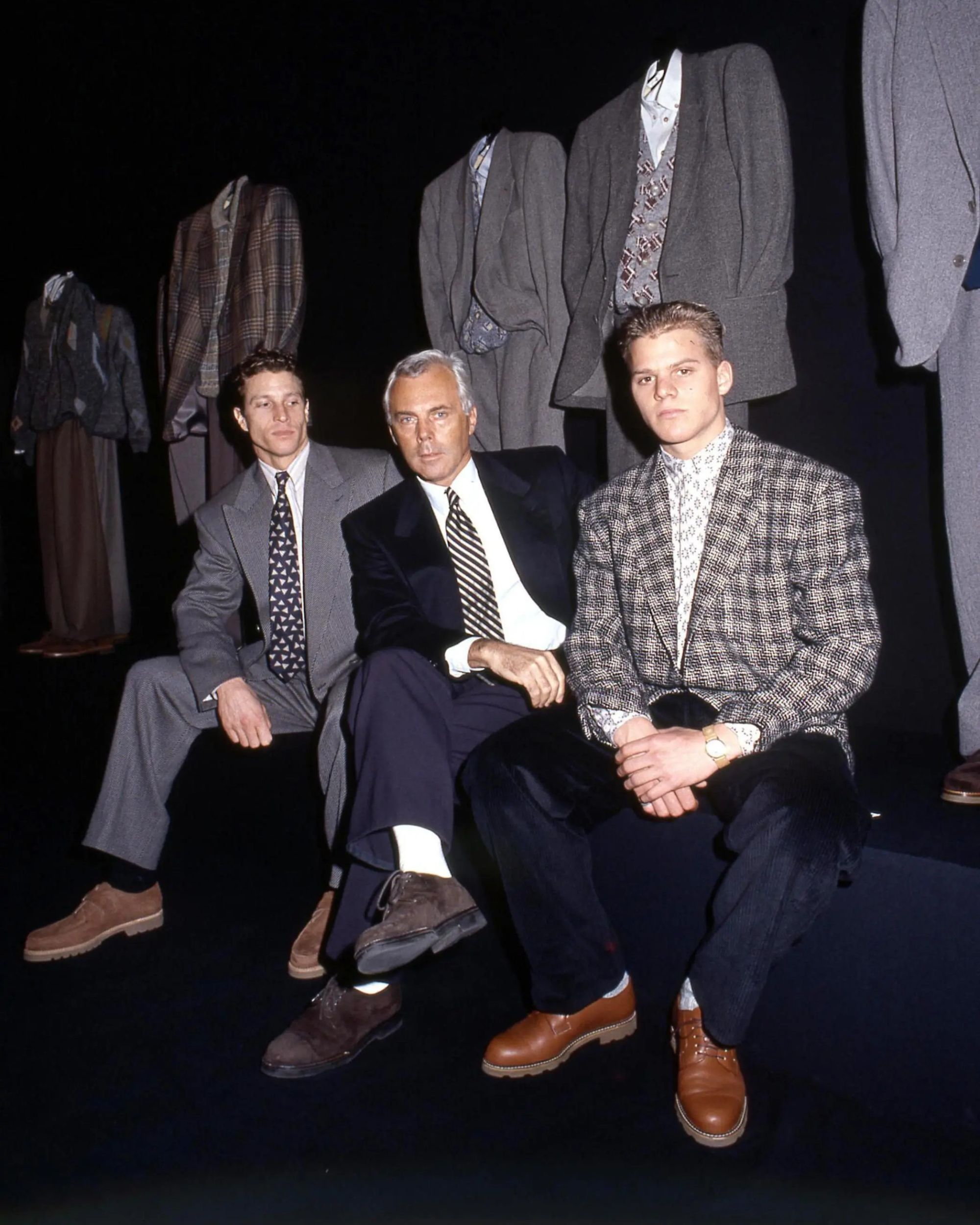

“One can look at the male suit as the barometer of cultural macro-changes. There are generations who have discarded or adopted their clothing based on what their fathers wore: in the 50s men wore suits and then in the next generation they stopped, while in the 70s there was a revival of a different type of silhouette that disappeared in the 80s to return in the 90s with Giorgio Armani and with a new interpretation of luxury”, explains Jacob Gallagher, Men's Fashion Editor at the Wall Street Journal and author of The Men's Fashion Book, published by Phaidon. “The goal of the book is to give a bigger picture, almost as a galaxy, to show how a designer operates in this overlapping of events”, reading major changes in society through the evolution of menswear is the ambitious goal that emerges by encyclopedic scope of the book: you’ll find approximately 130 designers, 100 brands, 70 icons, 40 photographers, 40 footwear and accessory designers, 30 retailers, 25 stylists, editors, and writers, 20 tailors, 15 publications, 15 models, and 10 illustrators, as well as art directors, influencers, milliners, and textile designers. Arranged alphabetically, the 500 entries spotlight living legends such as Giorgio Armani and Paul Smith alongside today’s most innovative creatives, including Ozwald Boateng, Alessandro Michele, Kim Jones, and Virgil Abloh, and cutting-edge brands such as Bode, Sacai, and Supreme.

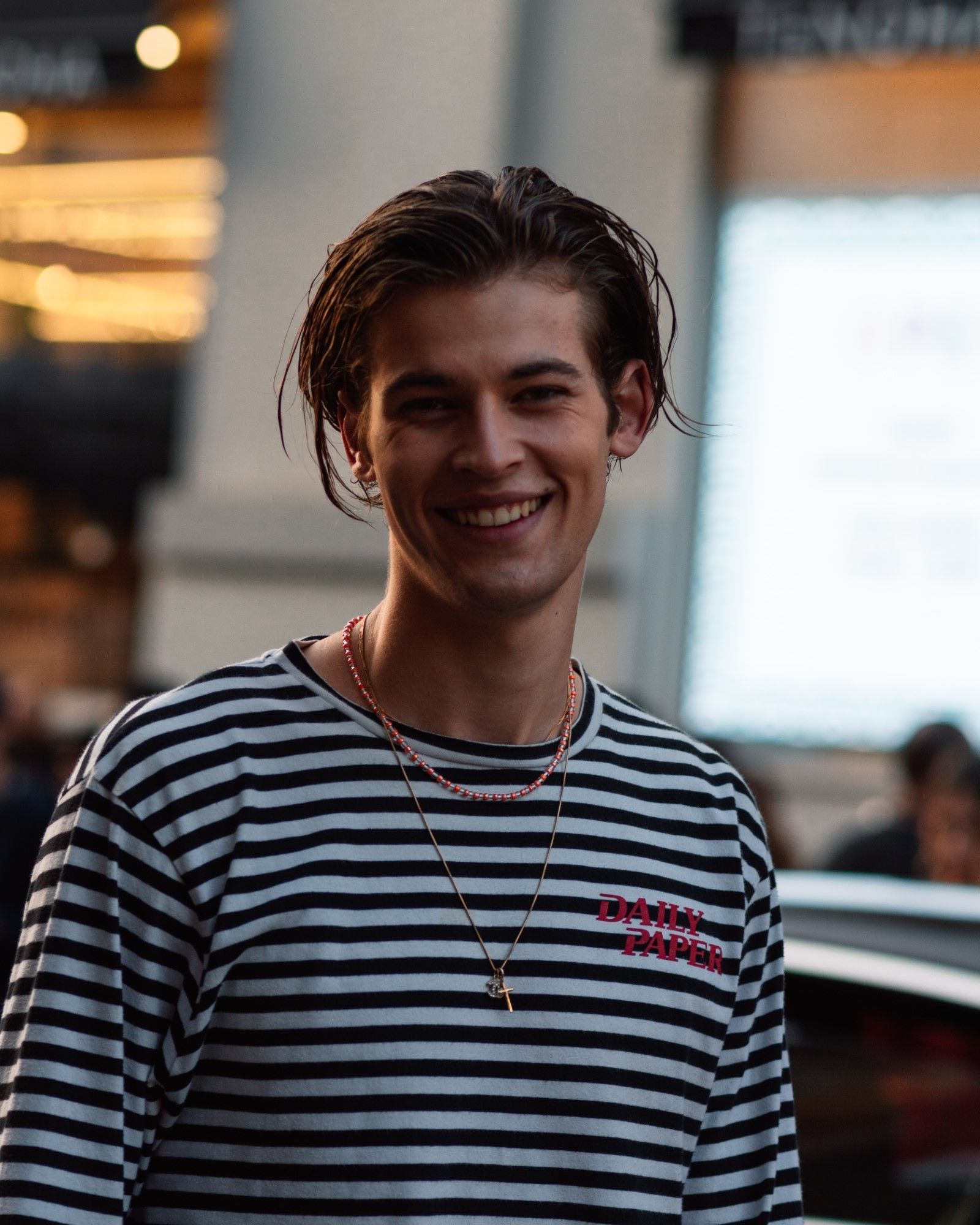

The book's method seems to paraphrase a famous quote from José Mourinho: «Who knows only about fashion does not know anything about fashion». And indeed the aesthetic codes of men's fashion according to Jacob «have always been grounded in the way people do dress, whether you talk about workwear, military or tailoring, they are all kinda “by the book” and there are rules in a certain way». Unlike womenswear which is historically more linked to the catwalk and the aspirationality of clothes, menswear «has always been in conversation with what people wear on the streets» and today culture in Western societies is experiencing a historical moment in which the redefinition of masculinity and its codified roles is at the center of public debate. The task of fashion is to mirror and accelerate these changes. From the ERL wedding outfit worn by Kid Cudi to the CFDA to the cover of Vogue by Harry Styles, contemporary fashion is becoming a tool to express the new meaning of masculinity, while influencing the debate around these topics. Then there are the external events that change the perception of what is "formal" or "elegant": the pandemic has clearly redefined the work uniform of a huge number of people by changing the «public perception of sweatpants, we often forgot that those garments where marketed as athletic wear».

Always looking at the men's suit as a cultural barometer for example, in the last collections before the pandemic you could see a return of the formal dress with more relaxed shapes and cuts. A type of approach to masculinity and the status symbol of the dress radically different from the sharp clothes of the 90s or the exaggerated ones of the 80s. Gallagher, however, emphasizes the cyclical nature of these trends. «I would also says that writing the book I had the feeling that “there’s nothing new under the sun”: Alessandro Michele at Gucci did an extraordinary reorientation of what men's fashion is and what could be call masculine, but then there is a British designer Micheal Fish who designed dresses for the David Bowie in 60s and 70s».

Two themes - the trend's circularity and nostalgia - which according to the author are two of the main industry's drivers, shifting the focus from the anxiety of releases towards archival research. «Depop for instance has helped to accelerate the degradation process of hypebeast culture by providing access to Gen Z to brands like Jean Paul Gautier or just stuff that looks 80s or 90s that’s what they after to». But going beyond the mere trend of vintage, according to Jacob internet and «the access to these platforms - Depop or even TikTok - have changed the understanding of what is new» in the most radical sense of the term: if the Y2K trend lives thanks to those who in the 2000s were not yet born, it means that it is not the classic sense of nostalgia, but something more complex where collective memories shapes the concept of new and old.

This vision explains apparently the rise of completly opposite trends: two good examples are on the one hand the metaverse and digital fashion on the other the return of craftcore and knitwear. «Metaverse has a huge market potential, and it’s natural that brands are gonna tap this huge audience that spend a major chunk of their life online» notes Jacob adding that «tangibile clothes will always have their value in real life». If the pandemic has been an accelerator of digital trends, it has created the effect posed by creating a return in demand for manual actions, such as knitwear: «There will be more of people making literally their own clothes, and when brands will fully embrace this new way of making clothes that is gonna be another revolution. It is actually a strange retro trend powered by the internet but in the 30s, 40s and 50s there were brands that use to sell fabric and pattern for people to make them at home».

In addition to the historical aspect, the book offers an overview of the interconnections and influences that have shaped current fashion, from Stüssy and his international family to the work of Rei Kawakubo whose remnants of influence can be found from Supreme to Louis Vuitton. In addition to designers and brands, then, there are those items that, like the men's suit, change their meaning depending on the historical and geographical context: the white tee can be a symbol of rebellion in the 60s, a blank canvas for the protest of Vivienne Westwood in the 90s or the object of desire in the hype culture of Supreme. The approach of The Men's Fashion Book may seem analytical and cold but instead the method used by Gallagher starts from the relationship between the individual and the fashion object within a social context: «Even people that tell me “oh I’m not that fashionable” they have all a lot of idea about how to style or just stories related to it, and I think this is just more valuable to my readers compared to a fashion show review».

The most interesting aspect of the book is precisely the duality in the creative approach: on the one hand the zoomed-in vision of a cultural evolution that spans almost a century, on the other the intimacy and sentimental complexity of the relationship between men and their representation.