The evolution of post-Soviet aesthetics How vodka, slav squats and adidas tracksuits entered pop culture

Last week, on the occasion of new year's eve, a funny parody of the classic Italian music shows, called Ciao 2020, aired in Russia, complete with 70s outfits, bizarre plastic shades and cheesy love songs. Seen from a Western perspective, the video seems together to be an authentic piece of Italian television and at the same time a parody of it – a contradiction and mirror of reality and fiction reminiscent of that period of Russian history in which USSR was crumbling but the citizens themselves lived convinced that nothing had changed, in a kind of surreal collective psychodrama that seemed to have come out of the avant-garde theater. A type of society that gave birth, after the collapse of the USSR, an imagery of social degradation, poverty and squalor which, soon became proverbial (think of SNL sketches based on the character of Olya Povlatsky, played by Kate McKinnon), denoted the perception that in the West one has of Russia – but on which fashion has also managed to capitalize.

These stereotypes are so strong that the pose of an individual who sits crouching on the ground without touching the floor, especially if he wears an adidas suit, is called 'slav squat' - actually a pose associated with Russian inmates who did not want to make contact with the icy floor of their prisons. All these stereotypes, actually, both in their humorous implications and in those concerning the field of fashion, they relate to the subculture of gopniks (In Russian го́пник), i.e. young people born and raised in those popular casermoni often associated with Soviet Russia but spread throughout the USSR, called khrushchevka – literally "Khrushchev slum", after the president USSR who had them built in the 1960s. Putin's Russia, engulfed in political scandals and economically on its knees by the pandemic and the oil crisis, now seems to be in a similar situation, and what was an offensive stereotype has become an aesthetically pop aesthetic that is still very edgy for European parameters.

This kind of national stereotype does not immediately fall into the category of offensive clichés, an example of which is that of the American redneck, but it is part of a wider movement of cultural consciousness or metabolization of historical facts that has had and still has humorous implications (the @lookatthisrussian account currently has 1 million followers on Instagram) but also implications and creative elaborations.

The post-Soviet style was Demna Gvasalia's work with Vetements and Balenciaga, who later became the vehicle to face a broader discussion on traditional aesthetic categories; on it Lotta Volkova founded a stellar career as a stylist first for Balenciaga and today with Givenchy; Gosha Rubchinskiy, before details of his sexual harassment of underage models came to light, was the most acclaimed prophet; and model and singer Sasha Trautvein also used edginess to launch her career and fame – quantified in 755 thousand followers on Instagram.

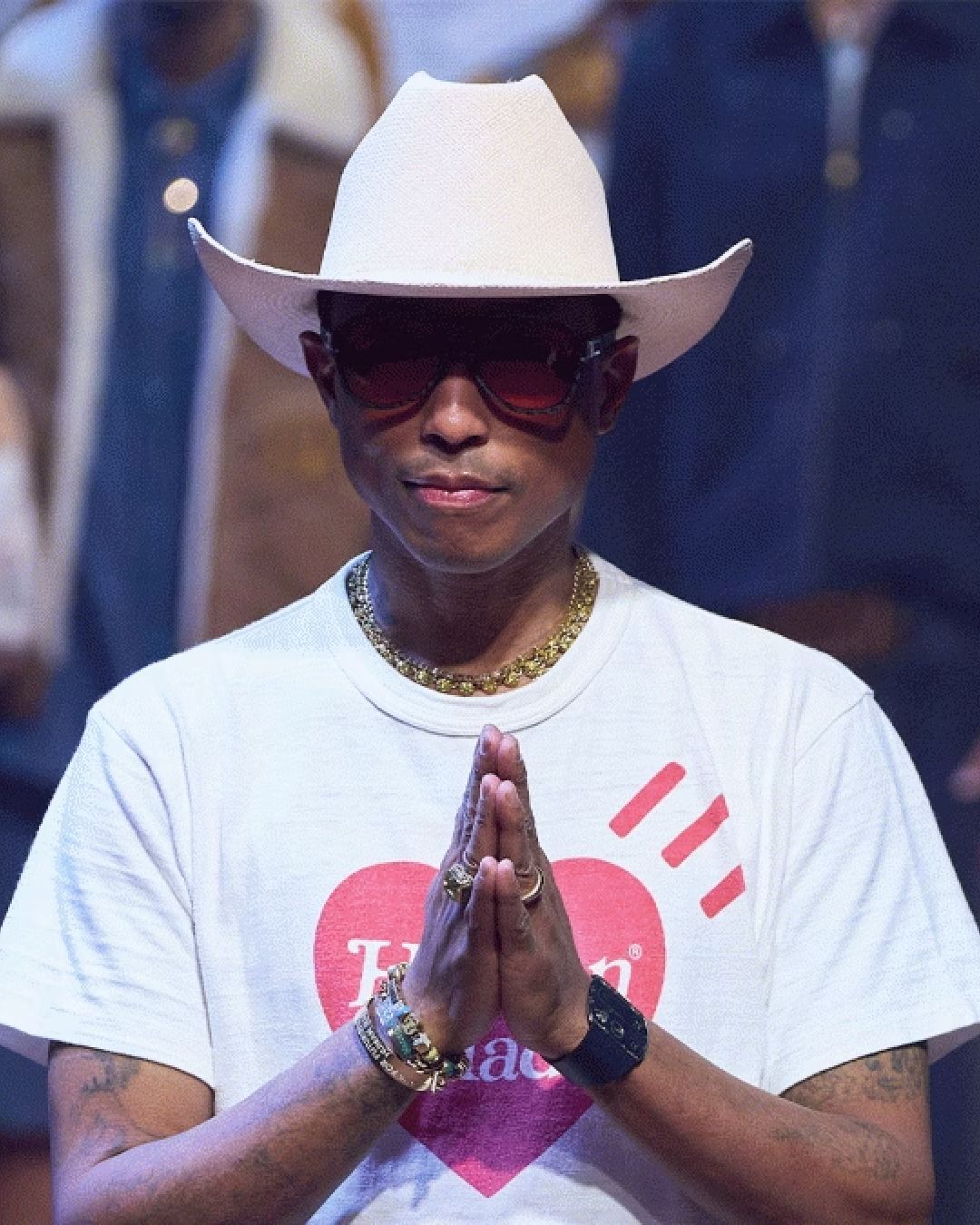

The appeal of this aesthetic, gopnik in the case of Russia and post-Soviet in that of the rest of the countries of the former USSR, rests on its own exaggeration, on its character as a parody of itself – in other words, on the fact that it is a cliché or not perceived or to some extent embraced. A controversial point that must be mentioned, however, is that of cultural appropriation: the gopnik aesthetic, born like all subcultures to be social and identity driven in contexts of poverty and abandonment, becomes the source of trends that are then "taken" from their context of birth by the big brands that reduce them to mere decoration - the best example of this process is the trend of babushka scarf, which originated centuries ago among the elderly Russians and then was picked up by A$AP Rocky, Gucci and countless other brands. What is certain, however, is that the interest it arouses remains linked to the fundamental ambiguity of Russia seen by the West, a country of strong lights and strong shadows (think of the recent attempted murder of the activist Alexei Navalny) who, as Winston Churchill once said, is 'a riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma'.