The Italian archive: fashion from a future past NSS

The Italian archive: fashion from a future past

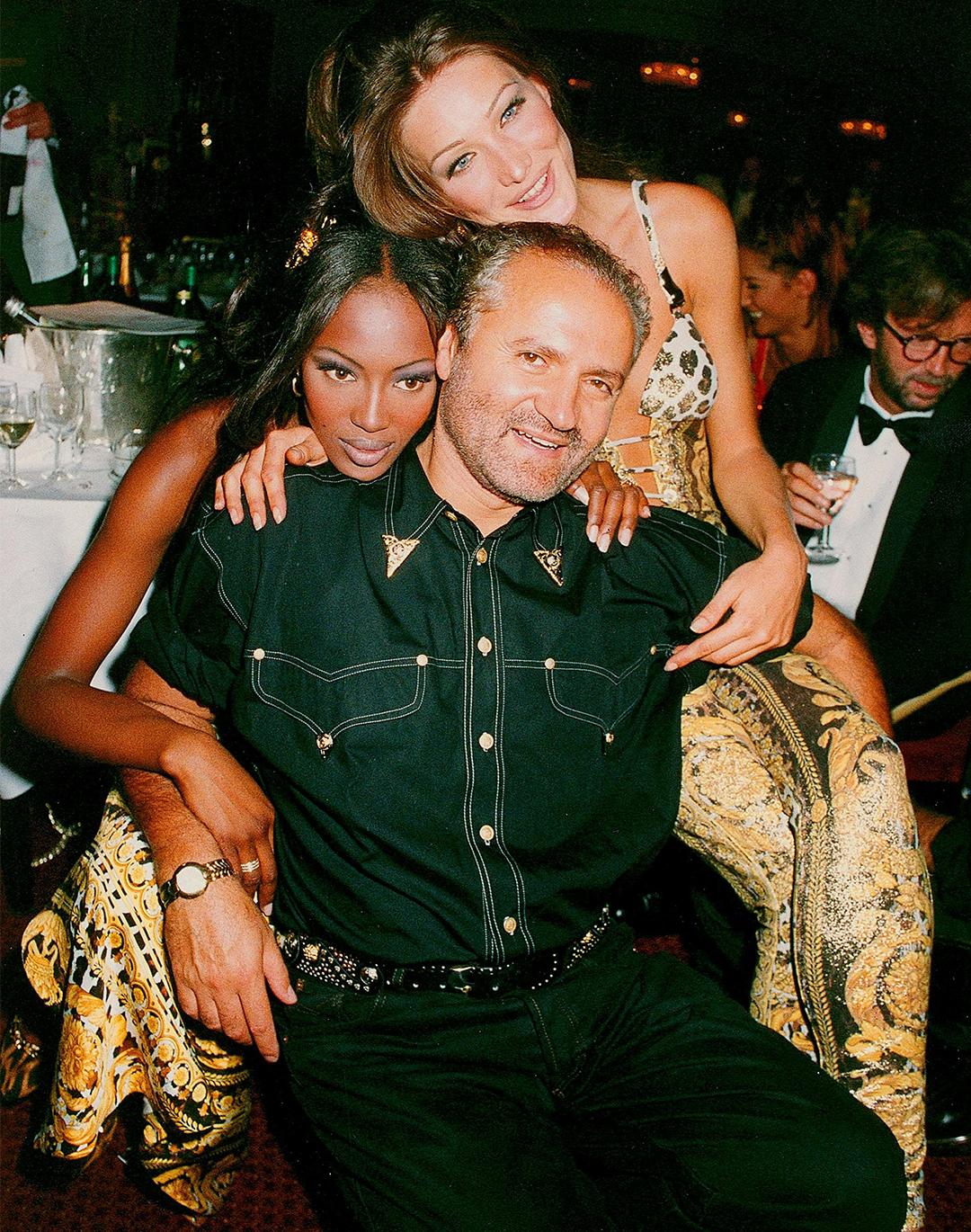

When the realization that something called "archival fashion" appeared in the industry's collective consciousness just before the pandemic, it seemed to many fashion enthusiasts that they had found a new purpose in life. Finding, buying, and appreciating archival garments took the passion for fashion beyond all the latest catwalks and glossy magazines, giving it an intellectual and in some ways antiquarian depth hitherto unheard of. The archive was an antidote to the genericness of contemporary branding that nullifies everything with the superficiality of its own appeal, and if on the other side of the ocean the early archivists collected the best pieces of designers such as Jean-Paul Gaultier, Raf Simons, Ann Demeulemeester, Carol Christian Poell, Helmut Lang and Takahiro Miyashita, on this side of the ocean, and specifically here in Italy, a question arose: where should be placed the enormous heritage of Italian vintage in the universe of "archival fashion"? Between flea markets and vintage stores, the old creations of the great Italian brands with their many diffusion lines the material to catalog and, often, discard is enormous. No fewer pages such as@archived, @archivereloaded, @inside.tag, @lost.garments and @constantpractice have begun to make their own selection featuring pieces from Dolce & Gabbana's FW03 collection, Emporio Armani's pants and jackets from the 1980s, Prada's 90s grails and designs from Massimo Osti and Mandarina Duck just to name a few. Beyond the more tactical-inspired fashion, on the other hand, on secondhand platforms, Gianni Versace's silk shirts are still selling for thousands of euros while Giorgio Armani's mainline vintage suits, the ones that are a bit oversized and so tunic-like, have been highly sought after.

However, what makes a certain dress signed by an Italian designer "archival"? When asked about this, the independent journalist Odunayo Ojo said that «the archive is the vintage that is coveted», establishing as its indispensable characteristics the presence of curatorship and therefore a critical filter that distinguishes between what is vintage and what is archivable; the historical relevance of the garment and its possible symbolic subtexts. Generally speaking, the existence of an archive presupposes that of an archivist, and the value of a certain item cannot be separated from the critical sense of those who select it among the rest of the other products. However, according to Zeke Hemme, founder of Constant Practice, a platform on which pieces by Emporio Armani, Massimo Osti, and Mandarina Duck often appear, there are no "archival" pieces and pieces that are not - only vintage design exists. At this point the question lies in determining how that design has aged: if a 1980s design is still desirable today, if it still tells us something and does not convey an idea of oldness then we are looking at a piece worthy of being worn and appreciated. As rigidly practical as this point of view is, in the face of the vast sea of Italian vintage, with all its sub-labels and its eagerness for commercial licensing muddying the waters, this kind of concreteness will serve as a diriment tool.

Consider, for example, the case of Gianfranco Ferrè: a distinguished couturier who brought real masterpieces to the catwalk, but also a commercial titan who granted fourteen different licenses for his brand, with a huge number of diffusion lines, having his name and monogram printed on an abnormal number of negligible t-shirts, handbags, and woolen hats. Distinguishing the proverbial chaff from the wheat is not as simple as distinguishing between mainlines and diffusion lines since, in the case of the latter for example, there is no shortage of examples of basic but very high-quality products. The same could be said of many of the "Jeans" lines that Versace, Armani, Trussardi, and Valentino produced in the 80s but also, leaving the realm of the big brands, much of that vintage found in flea markets, consisting of brands such as Rifle Jeans, El Charro, Carrera, and Facis just to name the most common ones that represent illustrious examples of a very solid Made in Italy, part of the pop culture of a few decades ago, but which today is unjustly forgotten. Too often it happens, that it is precisely external Instagram archive pages that give legitimacy to the archives of big brands: except for the designs of such illustrious lifelong brands such as Fendi, Gucci or Prada, Dolce & Gabbana's previously mentioned FW03 collection, as well as Roberto Cavalli's early 2000s creations and the hyper-functional treasures of Emporio Armani and C.P. Company have all been discoveries brought before an international audience by international archivists. Nevertheless, the "systematization" of Italian vintage, its subdivision, and cataloging would need Italian archivists on the spot who can recognize the high, medium, and low products of this galaxy and select the designs into a whole, if not coherent, at least complete.

In short, what is lacking in our country, is not so much the material presence of vintage clothes but more archivists who do the same kind of work in our country as the British or American pages mentioned above do in theirs. All of which on one hand it implies a process of research and documentation that is by no means easy, and on the other hand a work of persuasion towards the Italian public, which may be both reluctant to research and appreciate designer clothes that today we hear very little about, as well as to invest significant sums of money in great vintage pieces from big brands that have less immediate commercial appeal. However, the archive experiment, as put into practice this year by Gucci with the Vault project and Valentino with the Vintage project seems not only successful but also waiting for someone to implement it.