From Greek Epistles to Tinder: The Evolution of Love Messaging How did they do it in the Middle Ages without emojis?

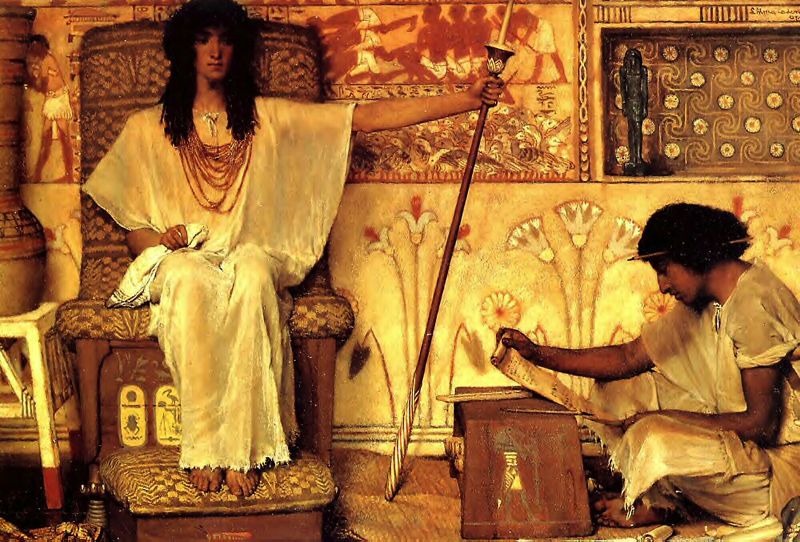

The oldest love letter in the world, curiously, is not a letter: but a message that is dictated by Princess Rukmini to a Brahmin who pronounces it for King Krishna in a sacred text of Hinduism that dates back more than 5000 years: «Oh Most Beautiful One of all the Worlds…», it started. And even if the Egyptian fragments are full of love letters, those of ancient Imperial China and Korea, it was necessary to wait for ancient Greece and, centuries later, Hellenism to hear about love in substantially more modern terms: from the verses that Sappho addressed to his students and companions, passing through the fragments of Anacreon, messages and letters often in poetic form that were one of the most sophisticated forms of those ancient civilizations that actually lived love in an extraordinarily modern way. Four centuries before Christ, Callimachus of Cyrene writes an epigram to young Archinus to apologize for showing up drunk at his home in the middle of the night – the modern version of a WhatsApp apology after a nice barrage of “Ehi, where you at? Wanna meet?” written at four in the morning after the disco and six gin and tonic. A more complete collection is given to us in the second century before Christ the mysterious Alciphron who recorded in his Epistles 118 love letters of the Athenians of the time. In the same period, in Rome, Ovid wrote the love letters of the mythological heroines – a sort of fan fiction ante litteram that had a perhaps unrepeatable success in the history of literature.

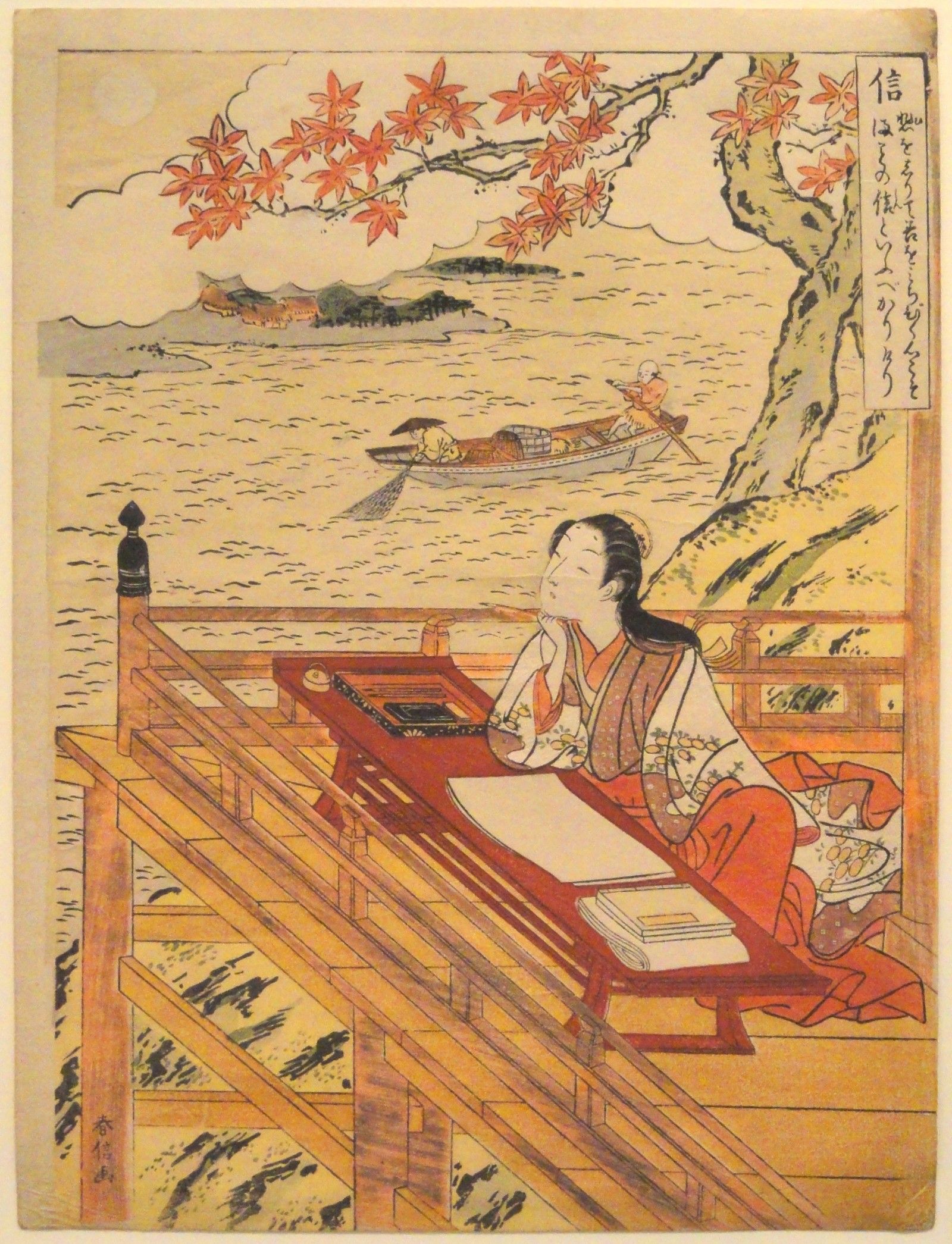

Skipping over centuries of history in which many love letters were written and read without the language evolving substantially, we arrive in Italy, in the Verona of the twelfth century, where the Modi Dictaminum of Maestro Guido explain in every little detail how to write a love letter – including the advice to exaggerate on one's feelings. More synthetic is in Japan where Prince Genji, as Murasaki Shibiku recounts, sends poetic compositions written on fans or precious objects to the right and missing. And if for Lady Murasaki the love letter is short, stringent and above all always cunning, in France the forbidden love story between Abelard and Eloisa (an illustrious theologian and his young student) produced perhaps the most famous love letters in European history. According to many girls present in nss magazine's newsroom and interviewed about it by the author of this article, however, such a long correspondence that results in nothing could have been a power move in the Middle Ages but today it would be less advisable. And if a message of love is always a good idea, sometimes in some cases they don't work. Do you know when you reread, months later, the smancerie you wrote to your ex? Here, the same situation of discomfort is given by the messages of love that Henry VIII sent to Anne Boleyn in the mid-'500 scribbling them secretly on the edge of prayer books. But we all know how that story ended.

@datmedievalprof The Middle Ages aren’t what you think. #fyp #MedievalTiktok #bardcore #shakira #hipsdonttlie This turned into a trend I dont know how (Shakira- Hips Don’t Lie) - Tik Toker

Other letters hide more moving meanings: in 1623, the Viscount of Villiers, mistress of King James of England, wrote chastely «I love you better than myself» before calling himself «Your Majesty’s humble slave and dog». During this time the idea of gallant love was born, especially on this side of the sleeve, at the court of the Sun King in France, where they practically exchanged so many letters and love notes to put Bumble's chats to shame. It did not have time to enter the '700 that letters had become one of the most famous literary genres: absolute masterpiece of that era was The Dangerous Liaisons by Chorderos de Laclos, a story that was among other things adapted into a cult film in the 90s called Cruel Intentions and that transforms love letters into icy tools of social engineering and ruthless conquest. With a bit of malignancy, Laclos tells us that the highest moment for love letters is also the lowest: when their form becomes sublime and highly studied, their purpose is none other than selfishness and ambition. Which then is why we use Tinder today, but okay. Things changed with the arrival of the new century and romanticism: from the various Werther, Ortis and Gothic heroines of Ann Radcliffe, passing through the letters to Beethoven's Immortal Beloved and those to Napoleon's Pauline Bonaparte, the love letter confuses the limits of private and public, shows the greatness of these protagonists of history and culture through their most poetic flights. Beethoven is so poetic, in fact, that his love letter becomes a plot point of the first Sex & The City film, which fortunately came out before Christ Noth was canceled and And Just Like That saw the light of day. Blessed times.

Letter after letter we arrive at the present day. If paper and postal services have evolved, not the same can be said of love letters – less cheesy and, in the case of those sent to soldiers at the front, quite spicy. But the real, big twist in the history of love letters comes with two historical figures soaring above Napoleon and Pauline Bonaparte: Tom Hanks and Meg Ryan in You've Got Mail – the first film in which the two protagonists fall in love via chatroom and email. It's 1998 and we are on the verge of a new era. SMS and emojis literally change the way we perceive communication: from Kelly Rowland who writes disconsolate messages to Nelly in the video of Dilemma in 2002, to the parents of all Italian teenagers who discover the enormous costs of the phone bill after the offspring has spent a night exchanging love SMS (for the youngest: there were times when Whatsapp and Tinder did not exist). Between chatrooms on Netlog, trills of MSN and girls with dubious identities met on Badoo, the real turning point came on September 12, 2012, the day the first version of Tinder dropped. It was like the discovery of fire: a sort of Pokedex for singles (and, in lucky cases, couples) that allowed everyone to flirt and exchange messages from their own home.

As Destiny’s Child is trending, this feels like a great moment to remember the time when Kelly Rowland texted Nelly on her Nokia using Microsoft Excel and got angry when he didn't text her back. pic.twitter.com/on7KudQOB1

— Amanda (@Pandamoanimum) November 29, 2019

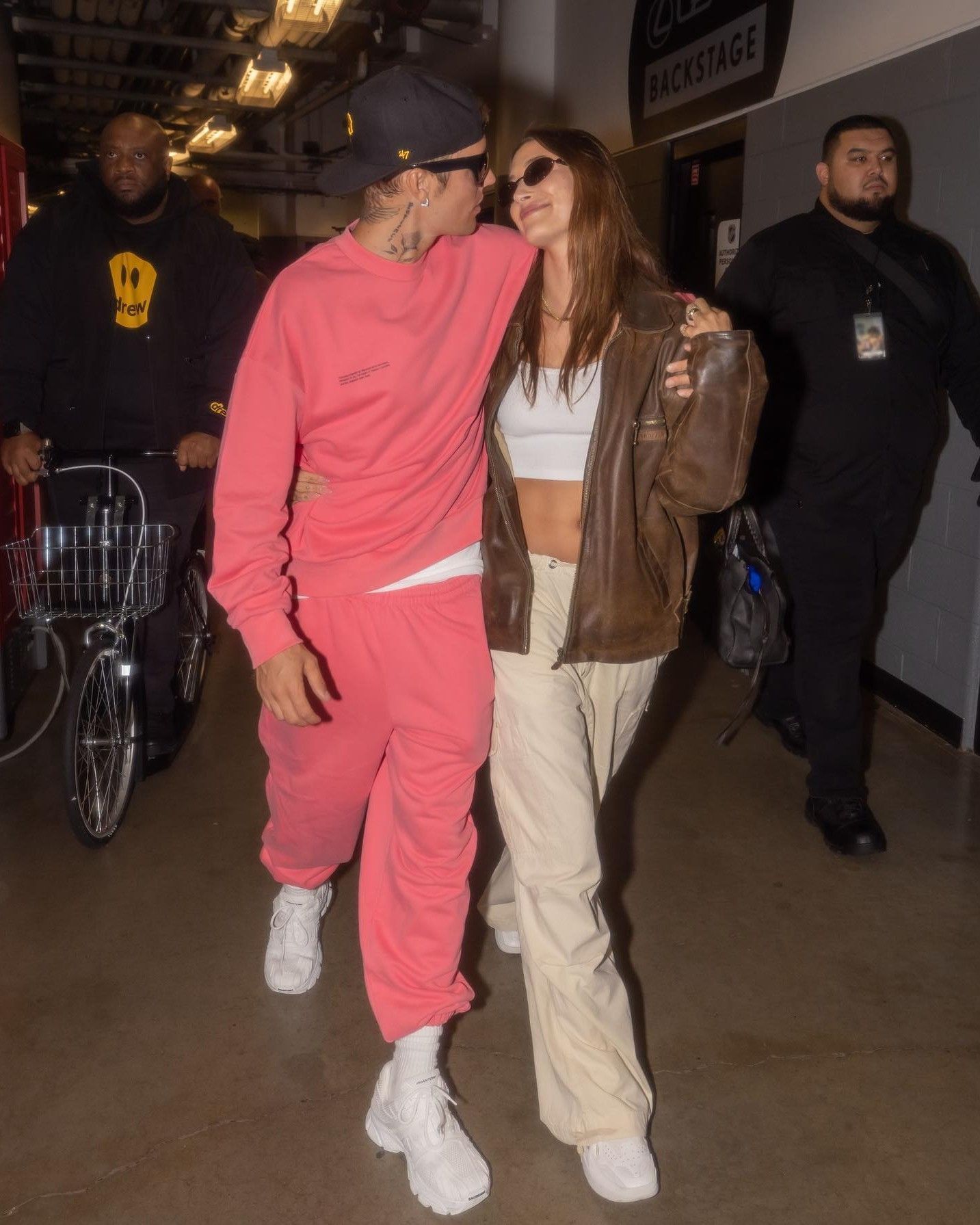

This is also the era of sexting, the one in which the inherent scandalousness and secrecy of the message of love is enriched with images, sounds with vocal notes and in which the long-distance relationship is filled by FaceTime and not by pages and pages of missives impregnated with perfume. Technology plays a fundamental role: the more it progresses, the more lovers around the world tear up the obstacles that separate them, first hear their own voice, then see each other – sometimes they even sleep live.

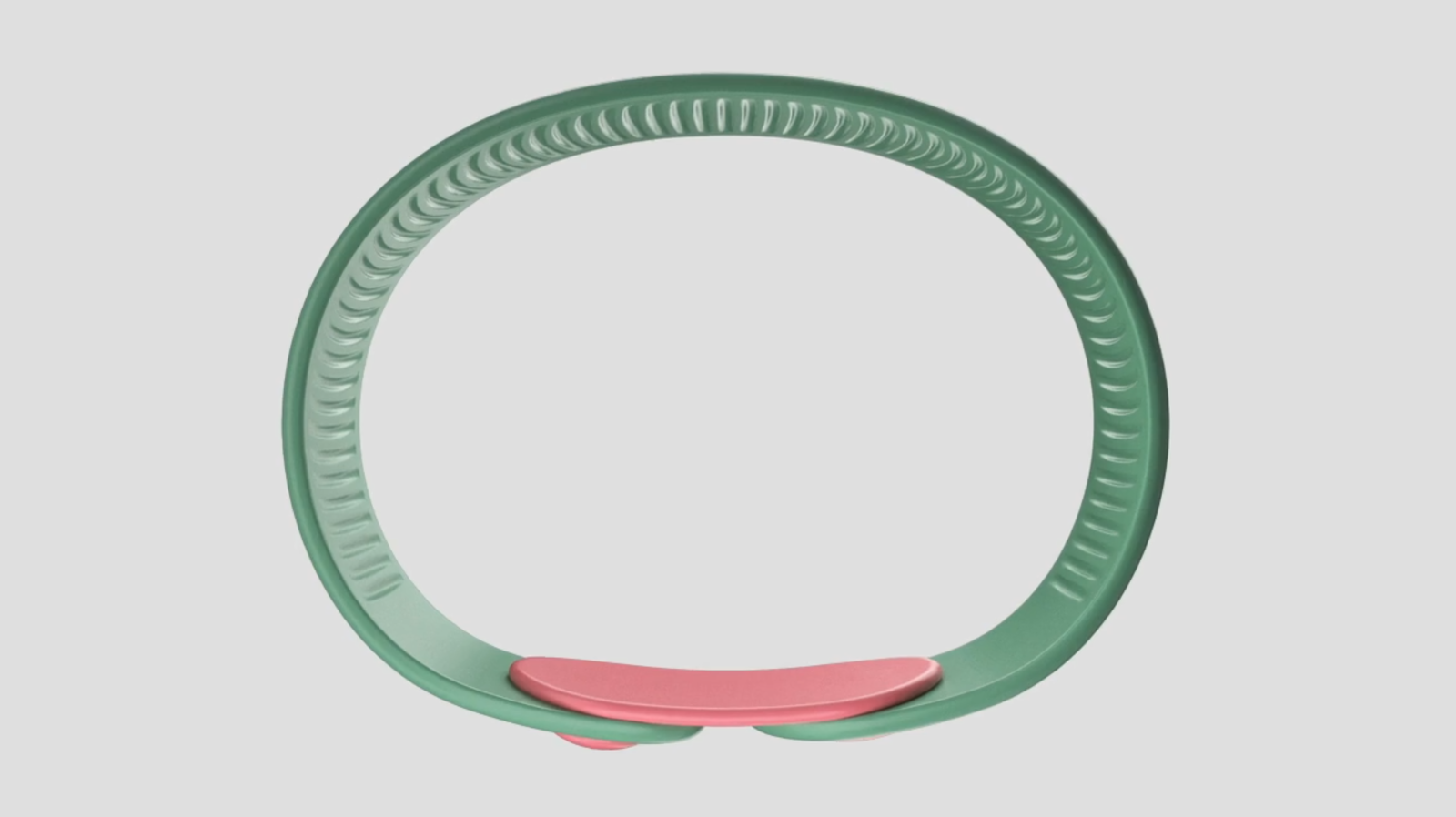

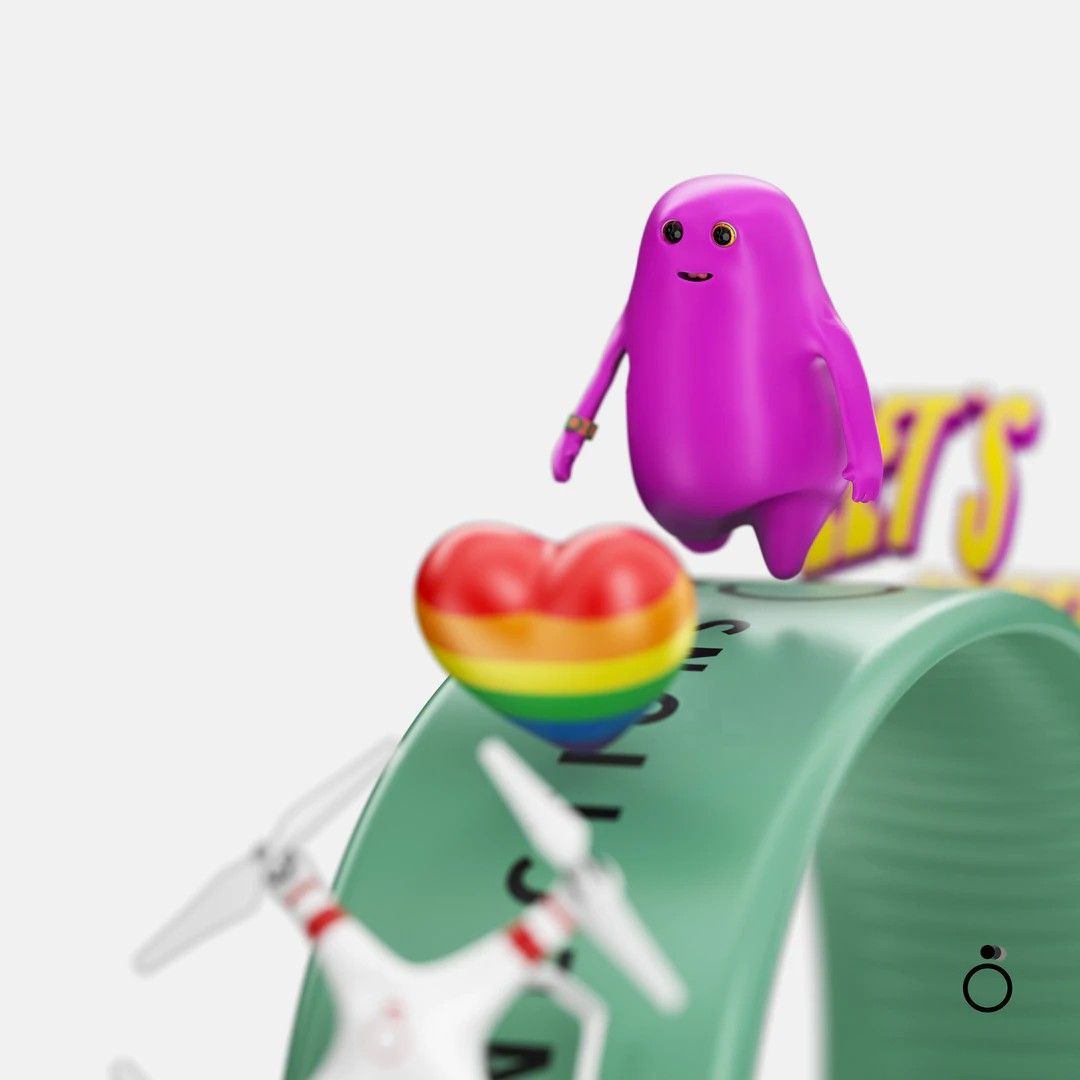

Recently, then, messages have moved: from the screen of smartphones to that of smart watches up to wearable technology such as the bracelets of B-R1NG Company, built in a patented material called XL EXTRALIGHT that through an internal microchip and a dedicated app allow you to create, customize and share 3D videos, images and NFT content to anyone who wears them on all existing social media. What Gen Z has in store for the future is not known: will there be a day when couples will transform their photos into NFT just as they hung padlocks on the Milvian Bridge in Rome? With new digital technologies, anything is possible.