A journey through the music of David Lynch Tthe director who turned images into notes

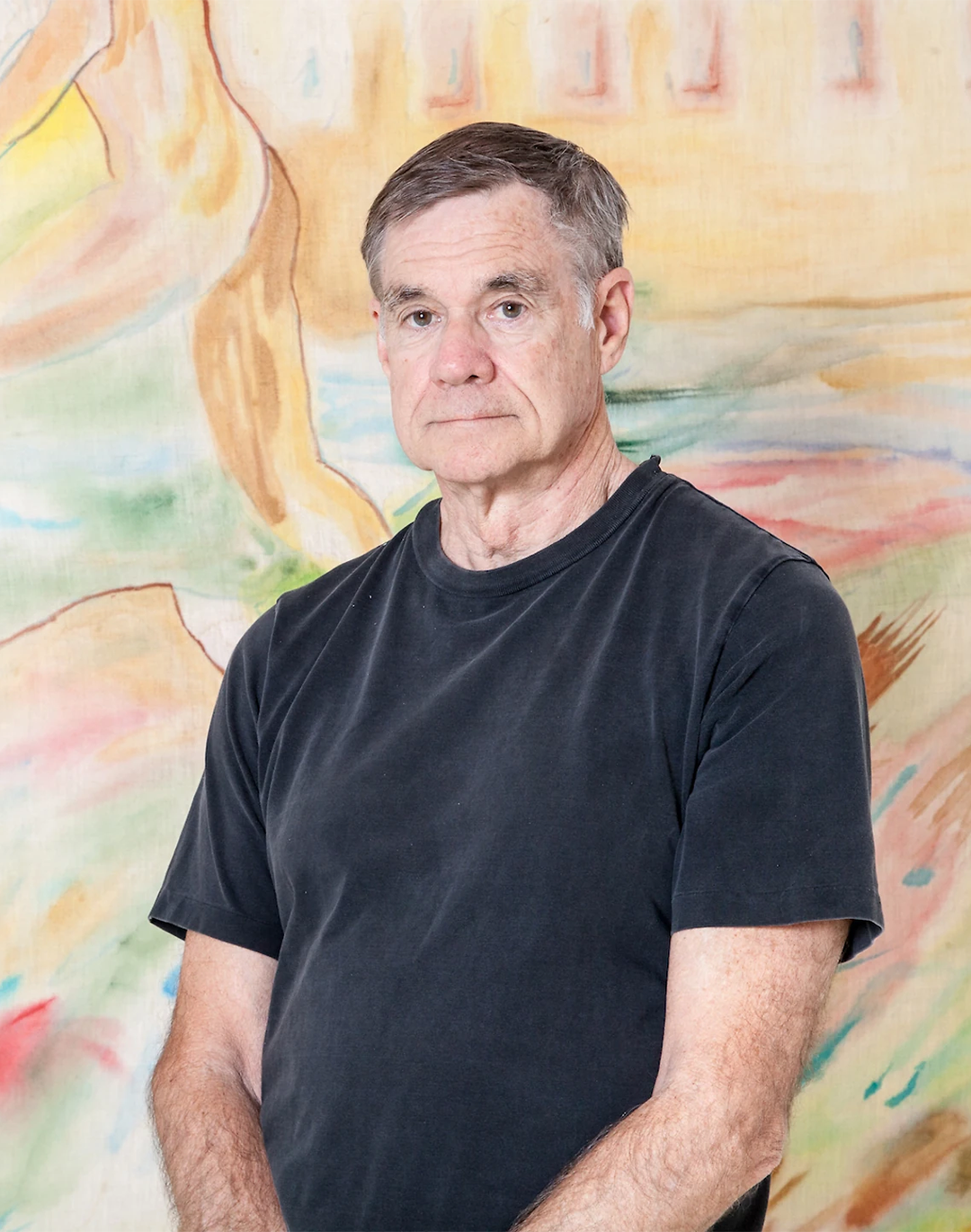

One year ago, David Lynch passed away, one of the few directors in the world with a style so unique and inimitable that it earned its own adjective – Lynchian – now commonly used to describe the typical atmospheres of his films, between the dreamlike and the unsettling.

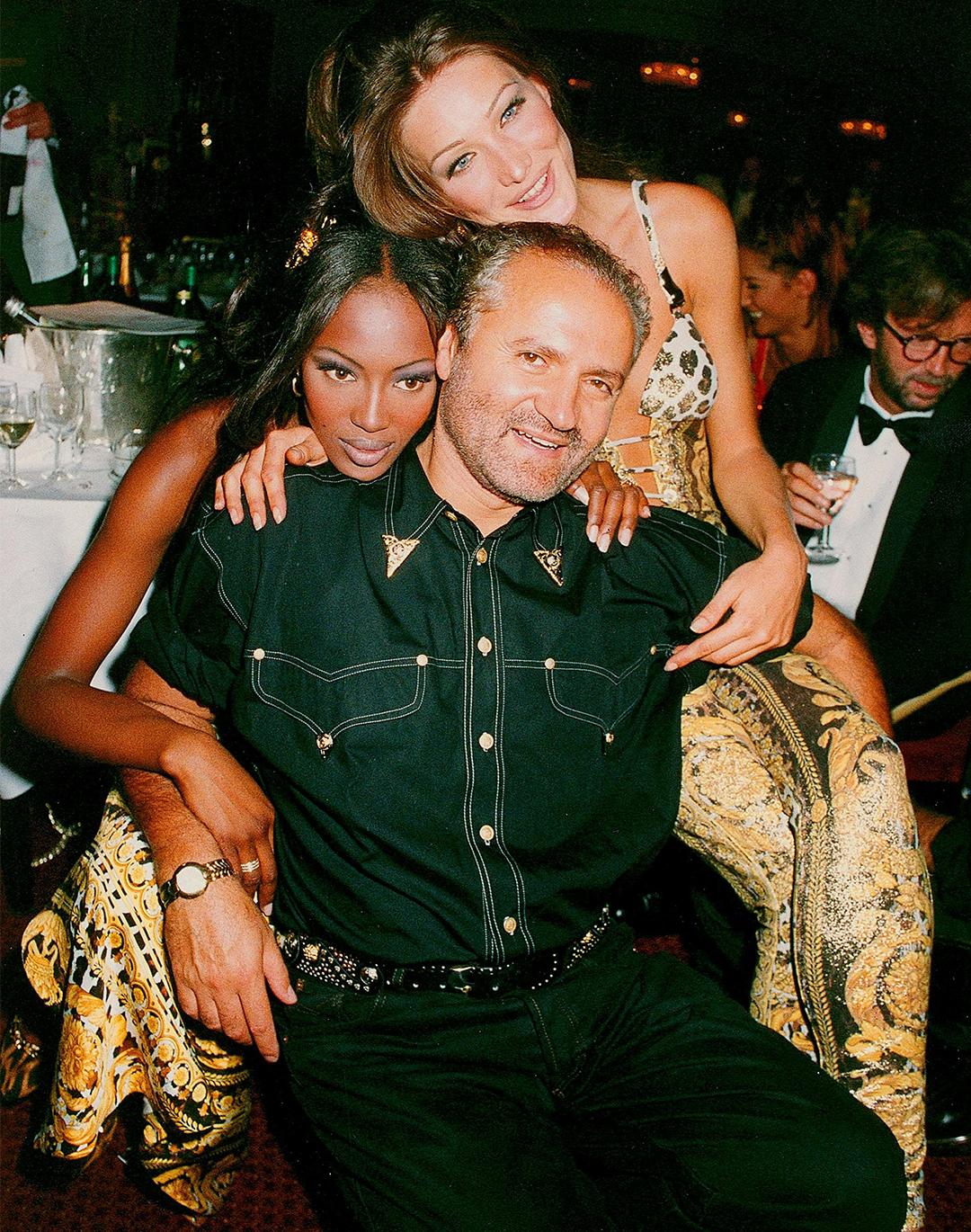

In the photo accompanying the announcement of his death, published on his official page on January 16, 2025, he was pictured holding a guitar. Not a camera, but a guitar. This alone is enough to give an idea of how deep and visceral his relationship with music was. «Music is magic,» the director once summarized, but it is worth exploring further.

From Music to Cinema

For this reason, one year after his passing, we decided to pay tribute to him through a journey into his musical world. Yes, today we can safely say that David Lynch, beyond being one of the greatest filmmakers in cinema history, throughout his artistic evolution was also an incredible music designer and a true musician, composer, and singer-songwriter in his own unique way.

As a child, Lynch also had a minimal musical training: he began playing the trumpet as a boy – with several photos documenting this – but it ended there. As a young adult filmmaker, however, he proved to be a skilled sound experimenter from the very beginning, even though – naturally – at the start of his film career he would never call himself a musician. In an old interview, he clarified, «I love sound and experimenting with sound. […] I’ve always been interested even though I am not a musician at all. But sounds tend towards music, and I love that border area where I can dance ever closer to music with sound effects.»

The use of sound effects and ambient noises with a musical sensitivity is a fundamental aspect of his aesthetic that accompanies him from his first short films and continues throughout the first part of his career. Decisive in this regard is his meeting with sound engineer Alan Splet, with whom he collaborated on the sound design of all his early works, from the late ’70s to the early ’90s.

The Whistle of the Wind

@rvngintl a one-of-a-kind mind, and a truly uncompromising, unconventional spirit. until tomorrow, david lynch ~ remembering david with a clip from eraserhead, soundtracked by “in heaven” from his collaborator, friend, and fellow visionary peter ivers #davidlynch #inmemory #peterivers #inheaven #eraserhead In Heaven (Lady in the Radiator Song) - David Lynch & Alan R. Splet

Artistically, Lynch did not actually start out as either a director or a musician. His first true love in art was painting. But one day he realized that the painting on the easel was no longer enough. He wanted to complete it by adding movement and a soundscape: what he wanted most – he would say – was to «hear the wind». This is how his aspiration to become a director arose, and at the same time, the idea of the first true Lynchian sound was born: the whistle of the wind, which we have heard so often in his films. We hear it clearly at the beginning and end of In Heaven (The Lady In The Radiator Song), the only true song in the soundtrack of his first film, Eraserhead.

The rest of the film’s soundtrack was described by Lynch himself as an «industrial symphony,» composed with Splet’s help, who recorded hours and hours of wind noise and combined it with electric hums, metal sheets, and working machinery to capture, as requested by the director, the sonic hell of an industrial city. This sound experience would influence and lay the foundations for the so-called industrial genre, later developed by bands such as Throbbing Gristle and Einstürzende Neubauten, or, in more ambient-adjacent areas, by Coil and Tim Hecker.

The Creative Partnership with Angelo Badalamenti

Another fundamental encounter for Lynch’s musical development was with the Sicilian-born composer Angelo Badalamenti. They met on the set of Blue Velvet (1986), where Badalamenti was initially brought in to serve as a vocal coach for Isabella Rossellini and help her sing the title track that inspired the entire film, Bobby Vinton’s Blue Velvet.

But the affinity between Lynch and Badalamenti was such that the latter ended up composing the entire film soundtrack. There was only one small problem: Lynch did not know the language of musical theory and therefore limited himself to describing the scenes, colors, and feelings, which Badalamenti then had to translate into piano notes. This initially surprising technique solidified over the years, culminating in the absolute masterpiece of the Twin Peaks soundtrack.

But to reach that, another fundamental piece was missing: the ethereal voice of Julee Cruise. Lynch would actually have preferred Elizabeth Fraser, captivated by dream pop after hearing her cover of Song To The Siren by Tim Buckley in the This Mortal Coil project. He would have done anything to have her in Blue Velvet, but being out of budget, Lynch rolled up his sleeves and tried to create something similar with Badalamenti. The result is their first true song written together: Mysteries of Love – music by Badalamenti and lyrics by David Lynch.

A classic anecdote is Lynch’s description to Badalamenti of how the piece should sound: «Play it like the wind, Angelo. It should be a song that floats on the sea of time.» Singing in place of Fraser was Julee Cruise, an old acquaintance of Badalamenti, whose voice – if possible – sounds even more ethereal and dreamlike than the original inspiration. All three were so thrilled that they continued collaborating in the theatrical show Industrial Symphony No. 1 and Julee Cruise’s next two albums, Floating Into The Night (1989) and The Voice of Love (1993). Most importantly, in the cult soundtrack of Twin Peaks.

Between Music and Storytelling

Without delving into the epochal impact the show had on television, we emphasize how much of that impact is also tied to the amazing soundtrack, once again composed by the renowned Lynch-Badalamenti duo, with the sparing addition of Julee Cruise’s voice, used in three emotionally powerful tracks: The Nightingale, Into The Night and Falling. The instrumental adaptation of the latter would become the evocative and unforgettable opening theme of the series, capable of plunging the viewer/listener into a deep sense of peace, nostalgia, and romantic longing: the descending chords are analogous to the act of falling in love and, in Lynch’s world, to the act of falling both physically and metaphysically.

But the centerpiece is the Laura Palmer Theme, the girl around whom the mystery of the series develops. Badalamenti recounted in a video the moment the piece was born: Lynch described what Badalamenti should imagine to extract the notes, first slow and dark, «as if in a forest at night surrounded only by the sound of wind and animals,» then suddenly a celestial opening, the appearance of a girl in the distance approaching, making the melody rise higher and higher on the Fender Rhodes, until reaching the climax, then fading back into darkness. At this point, music is truly magic and its success was remarkable.

In 1992, another turning point came with Fire Walk With Me (1992) – the prequel to Twin Peaks: here Lynch is credited as sound designer and no longer just describes songs or writes lyrics as he had in the past, but for the first time also composes the music himself. This gave rise to his first rock instrumental titled The Pink Room: slow, hypnotic, and sensual, like the scene it accompanies in the film.

Sound Designer Activity

Lynch’s work as a sound designer consolidated with subsequent films, particularly Lost Highway (1997) and Mulholland Drive (2001). The former features a formidable soundtrack, which, in addition to Badalamenti’s orchestrations, includes a selection of tracks curated by Trent Reznor of Nine Inch Nails (future Oscar winner). Reznor recounted that he created the track Driver Down based on the quirky instructions Lynch gave him, similar to the methods he used with Badalamenti. Specifically, Lynch allegedly told him for the final scene: «the sound of a box from which snakes jump out hissing in your face». Lost Highway is also the film where Lynch finally realized his dream of including the much-desired *Song to the Siren* by This Mortal Coil in a scene of dazzling beauty.

In Mulholland Drive (2001), Lynch manipulates Badalamenti’s orchestral tracks as he sees fit to create the desired unsettling effects. In addition to their instrumental pieces, the film also contains a stunning version of Crying by Roy Orbison sung in Spanish by Rebekah Del Rio (Llorando) and other tracks (Go Get Some, Mountains Falling) from Bluebob (2001), Lynch’s first true music project, where he plays guitar alongside the more experienced John Neff. Here we hear Lynch’s unconventional avant-garde guitar – a 1997 Parker Fly, halfway between guitar and synthesizer.

Solo Career

@sleepwalkrecords david lynch albums and soundtracks rest in peace to the greatest director #davidlynch #twinpeaks #twinpeakssoundtrack #crazyclowntime #bluevelvet #moviesoundtrack #davidlynchmusic #cdcollection #fyp #angelobadalamenti #bluevelvetmovie #mullhollanddrive #eraserhead #theelephantman #kylemclachlan #firewalkwithme #losthighway #dune #wildatheart #davidlynchmovies Laura Palmer's Theme (Love Theme from Twin Peaks) - Angelo Badalamenti

At this point, Lynch had only to sing. He officially did so with the soundtrack of his last film INLAND EMPIRE (2006). Lynch not only wrote two excellent tracks, Ghost of Love and Walking in the Sky, but also sang them himself, altering his voice through various effects, since traditional singing was not his strong suit. The film marked the detachment from Badalamenti’s guidance and inaugurated a new vocal collaboration with the alien singer Chrysta Bell, who performed the best song of the set (Polish Poem), and with whom Lynch would work until shortly before his death. Lynch also sang on the Danger Mouse and Sparklehorse The Dark Night Of The Soul (2009) albums, where in addition to overseeing the project’s graphics and videos, he also appeared as a vocalist on a couple of tracks: the poignant Star Eyes (I Can’t Catch It) and the unsettling title track.

At this point, Lynch was truly ready to walk in the world of music on his own. In 2011, he released his first true solo album, Crazy Clown Time, and two years later followed with The Big Dream (2013). Both albums are particularly dark (could it be otherwise?), featuring a raw, industrial blues sound, sometimes sparse. What limited their radio potential was not so much the dark atmosphere as Lynch’s voice, which was not always up to the task. The tracks that stand out the most are those performed by two real singers: Pinky’s Dream in Crazy Clown Time sung by Karen O of the Yeah Yeah Yeahs, and I’m Waiting Here with Lykke Li in The Big Dream.

Lynch’s musical journey continued with the 2017 return of Twin Peaks, where he worked with sound designer Dean Hurley and used the Bang Bang Bar as a device to close each episode with performances by kindred artists (notably, the dream pop of Chromatics and Au Revoir Simone and the return of Rebeka Del Rio and Julee Cruise). The journey culminates with the 2024 album released with Chrysta Bell Cellophane Memories. The final track’s last verses – Sublime Eternal Love – summarize his musical poetics: And the noise turned into music / And the notes had a feeling. David Lynch is no longer with us. But fortunately, there is always music in the air.