In the tussle between Rome and Milan, Naples won By Walter D'Aprile

In the Italian debate, whenever we talk about the “place to be”, the clash has always been between Rome and Milan. Two very different cities that, for decades, have competed for the title of the country’s “economic capital,” and with it the future of thousands of students, businesses, and creative industries. In terms of GDP, Milan came out on top. A small metropolis, just a seventh the size of Rome, which, despite its scale, over time began to compete on the global market as a creative Mecca, holding its own against Paris, New York, and London. But the match was never truly fair: the breakneck pace of this forced growth, the silent climb in a heavyweight fight, eventually led the city to collapse under the very premise of progress that had fueled its rise.

Between Milan’s growing pains and Rome’s endless scandals, what really tipped the balance was a New York Times piece in 2019 that described Naples as “the quintessential other Italian city.” Never historic enough to rival Rome, never efficient enough to compete with Milan, the Neapolitan capital had long gone from being mocked as the laughingstock of Italy, between “Napoli cholera” and Gomorrah, to being romanticized. Through the lens of Sorrentino and the iPhones of American tourists snapping pictures from ferries, some would say even fetishized.

Tre mesi fa mi sono licenziata perché milano mi stava mangiando viva e vivevo di stress donando anima e corpo ad un’azienda che mi sfruttava e che lavorava per i cattivi del mondo. Dead Line senza senso, mobbing, straordinari non pagati.

— sigh react (@esseressere) June 24, 2024

With the international boom of Elena Ferrante’s saga, My Brilliant Friend, and the post-pandemic revival of “slow living”, Naples suddenly became an idyllic postcard for millions of visitors. Overnight, Neapolitan identity was no longer something to be ashamed of but something desirable, even marketable. The same media that for years only covered Naples in the context of tragedy, or ignored it entirely when speaking of Italian culture, now report on its folklore, its traditions, and its “Neapolitan renaissance.”

Il Post, citing Roberto Napoletano, spoke of a “paradigm shift,” with the editor-in-chief of Il Mattino stressing how Naples had moved from being synonymous with sloth and the deadly sins to a “world-class city of culture leading the South’s economic rebirth and attracting both capital and tourists.” Even Rivista Studio, in its “Gran Turismo” edition, noted how in the early 2000s Neapolitans couldn’t care less about tourism—so much so that “those who would have mugged them fifteen years ago are now ready to rent them a flat.” But perhaps the peak of this performative fascination came with Vogue Italia’s August 2021 issue, The Napoli Issue, a glossy narrative full of binaries and superlatives.

In the end, however, this narrative of Naples, often built by outsiders, transforming it into a slow-life paradise, a creative lab, or a tourist brand, exposes a crucial point: the issue is not so much the cities themselves, but the stories we build around them. It’s a matter of representation, but above all of relationships. Because a city is not just a set of streets, buildings, or landmarks, but the way we live it, the questions we ask of it, and the answers it gives back.

Italo Calvino reminded us in Invisible Cities that whether we think positively or negatively of a place depends on the answers it provides to our needs in the present. For years, following the blueprint of American socio-cultural hegemony, we dreamed of wide boulevards lined with skyscrapers, so tall they blocked the sky. But this tiered model, of vertical levels climbing toward the top of society, inevitably creates discontent—or rather intensifies the frustration of those excluded from the tower.

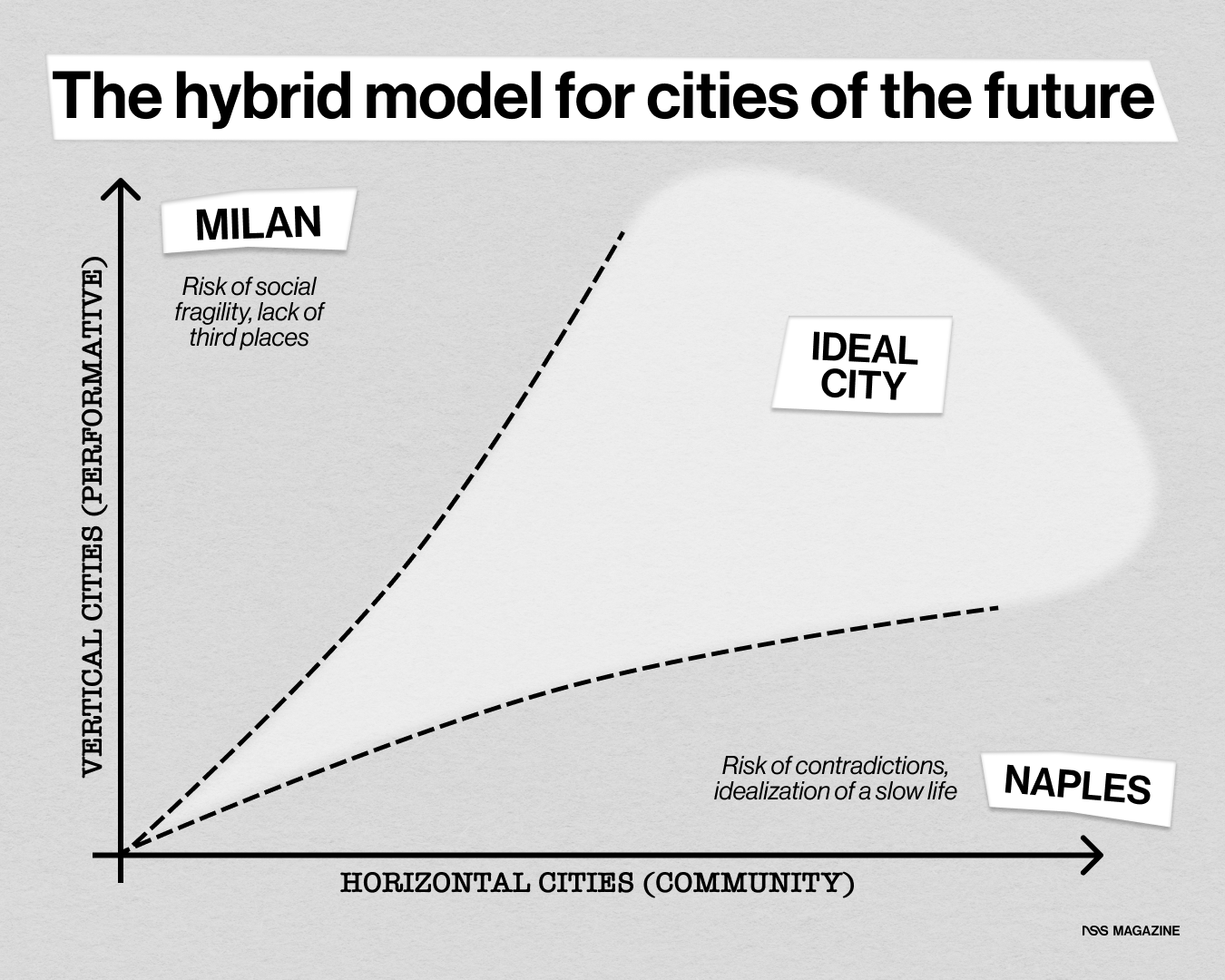

So if today Milan is the vertical city par excellence, its antithesis - the flip side of the same coin, with all its contradictions - is Naples: one of the few cities that lets us imagine a horizontal society. Not just in urban terms, but horizontal in the sense that the city can stretch out, can open up, dreaming of inclusivity and dialogue between the different classes living in it day by day. Naples, almost unconsciously following the Milanese model, has itself become a brand.

Just as we talk about “Ti odio Milano Ti amo,” or use “NoLo” to rebrand North Loreto, we now talk about “brand Napoli.” We talk about “J’adore Napoli”, a pseudo-slow-life dream that places human values above performative ones. Yet these values, which appear to fuel Naples’ revival, must become catalysts for the wealthy and ultra-wealthy, so they invest in the city and finally generate that flow of perpetual capital that allows young Southerners to stay and build the Naples of tomorrow, rather than moving elsewhere. The City and its institutions know this, and they’re trying to act on it daily. The America’s Cup 2027 will surely be a major test to see whether Naples’ horizontal model, carried forward almost unwittingly, learning from Milan’s mistakes, can stand up to the challenge, while Milan pays the price of being the overachiever.

The problem, after all, is not Milan becoming vertical, but a city forgetting it must also be horizontal, expanding not just its buildings but life itself beyond the center. The City knows this and keeps working on it, but the industrialists, the wealthy, and ultra-wealthy do so less, because by Thursday they’re already gone beyond the city walls. And that is the real issue of a place like Milan, or any metropolis designed this way: by Thursday, they start to empty out. Because the rich, the nouveau riche, the ultra-rich—those who insisted on building this vertical city—are also the first to flee to their weekend homes when it becomes unlivable. Not fleeing the city itself, but the image of the city they themselves created.

Of the suspended Milan of Covid, torn between resuming its relentless pace or slowing down, we’re left with only a Catullan odi et amo. What was once the kingdom of opportunity now seems like a kingdom of urban disillusionment, child of a capitalist bourgeoisie forever chasing the ultra-rich and at risk of vanishing in the process. But Milan should not be demonized. Its fragilities run deeper and are more visible than its contradictions. They must be lived with and healed. Fragile Milan is a city too tall, visible from the sky but absent on the street. Yet if we return to the streets, in search of third places, of a humanity lost in the frenzy of building, we might climb again, this time truly inhabiting the upper floors.

Like a brand, the metropolis must, on the one hand, be attractive to investors, but on the other also close to the needs of its consumers, its citizens. Both sides, of course, come with their pros and cons, their flaws and strengths, which must be debated in an open dialogue that first and foremost considers the needs of the community. To explain it better, imagine a Cartesian grid: on the horizontal x-axis sits Naples, and on the vertical y-axis sits Milan.

And we should try to place the different communities critically but constructively within this framework, making the most of the space. Keeping in mind that leaning more toward Naples means accepting Milan’s fragilities, while leaning more toward Milan means accepting Naples’ contradictions. Because clearly, without contradictions, there are no fragilities. And without contradictions, we wouldn’t be human. Precisely because our questions have changed, we now need new answers. Answers that can only come from this hybrid model: yes, vertical, but above all, horizontal.