How the phenomenon of “Non è la Rai” anticipated TikTok by 30 years A new idea of television, which ushered in a new era

If on social media Berlusconi’s twenty-year era in Italy has become a source of ironic-nostalgic memes, Millennials (who were just children at the time) still remember the atmosphere of those years. An atmosphere captured on screen by films like Sorrentino’s Loro and Moretti’s Il Caimano, by the entire cinematic body of work of the Vanzina brothers, or by the historical-noir miniseries 1992, which fictionalizes the story of Tangentopoli and features Berlusconi among its protagonists. Beyond actual politics, Berlusconi made his presence felt throughout the country via mass media and television: his was the era of anime and The Simpsons aired at lunchtime, of Striscia La Notizia and its showgirls, of Mike Bongiorno, of Lamberto Bava’s miniseries, of Big Brother and Men and Women. A television era of excess and frivolity that began, perhaps unofficially, with a seemingly light-hearted program that left an indelible mark on the country’s pop culture and, among other things, anticipated social media—specifically TikTok—thanks to a format based almost entirely on spontaneity and improvisation. That program was Non è la Rai. Thirty years after the show ended, considering the vast landscape of 1990s Italian television, few programs have been able to capture the public’s attention, sharply divide viewers, critics, and intellectuals, and represent an entire cultural phase as iconically as Non è la Rai. «It’s still airing today,» Irene Ghergo, one of the show’s writers whom we interviewed, told us, «it’s still modern, it hasn’t aged.» And to fully understand the genesis and impact of this media phenomenon, we need to start with its creator: Gianni Boncompagni, an innovator, provocateur, brilliant and controversial author who knew how to read and anticipate changes in Italian society, turning them into television spectacle.

@atlaskaneyt Ultima puntata non è la Rai 1995 Ambra Angiolini ultima in lacrime #trash #anni90 #mediaset #storia #amore All I Want For Christmas Is You - Mariah Carey

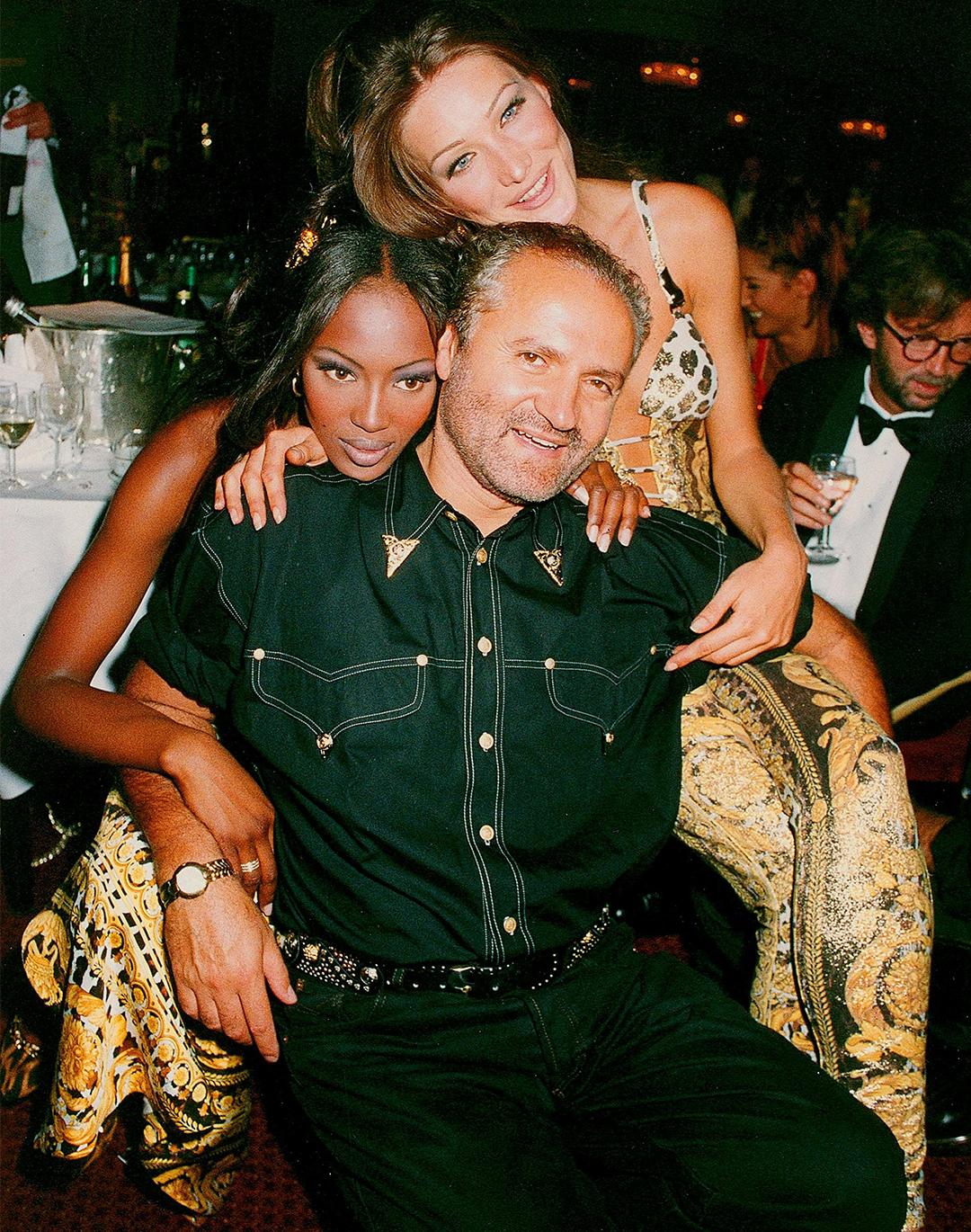

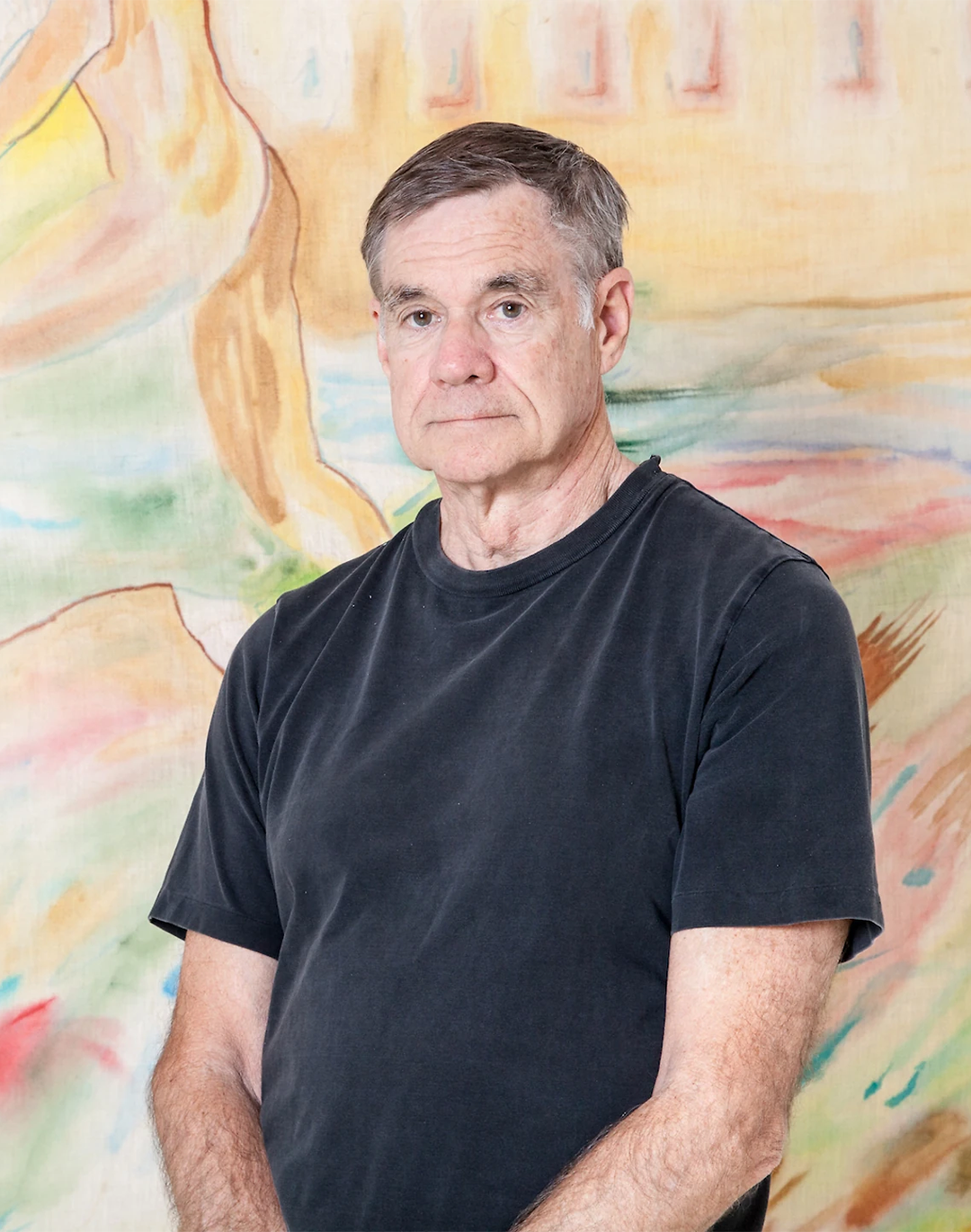

Born in Arezzo in 1932, to a military father and homemaker mother, he lived in Stockholm from age 18 to 28, studied graphic design and photography, worked in radio, and even started a family. Upon returning to Italy in the early 1960s, he entered and won a RAI competition for music programmers, thus beginning his career in public radio broadcasting, where he immediately introduced a new, fresher, more direct and youthful language. Together with Renzo Arbore, in 1965 he created cult programs like Bandiera Gialla and Alto Gradimento before moving to television in 1977 with Discoring, followed in 1980 by Superstar and then the legendary Pronto, Raffaella? with Raffaella Carrà, the first Italian TV program to introduce live call-in games in 1983—a revolution that brought the show to unheard-of viewership peaks, surpassing 9 million viewers. When Carrà left the show, Boncompagni continued, but in the early 1990s, he received an offer from Silvio Berlusconi to bring this moneymaker to Fininvest networks. «Berlusconi understood and gave him carte blanche,» Ghergo tells us. «He was a visionary and gave Gianni confidence in a concept that wouldn’t have been accepted elsewhere. And indeed, the sequin-studded, thigh-baring TV suddenly seemed outdated.» The initial idea was to replicate the format of Pronto, Raffaella? but that was set aside—what was needed was a new product that could reflect the emerging consumer society of post-economic boom Italy. Thus, Boncompagni conceived the idea of a show free of public TV’s pedagogical, cultural or educational ambitions, «completely extemporaneous, unscripted, based on natural talent,» as Ghergo recounts. A show capable of capturing the attention of a new market demographic: teenagers. Non è la Rai was born.

Ironic and irreverent from the title alone, openly opposing the television of sequins, evening gowns, and teased hair and «the marbleized audience» as Ghergo defines it. The first episode of Non è la Rai aired in September 1991 on Canale 5, at noon. Hosting were Enrica Bonaccorti, Antonella Elia, and Yvonne Sciò. In the Centro Safa Palatino studios in Rome, more than 100 girls aged between 13 and 19 («lively,» as Ghergo calls them) took turns dancing, lip-syncing, and participating in call-in games.«It wasn’t a high-ratings format but it was revolutionary,» Ghergo recalls. The set featured a four-seasons-themed stage where the girls performed in rotation, «participating in spontaneous songs and dances.» The format had something entirely new: a chaotic, almost psychedelic energy, generated by the interaction of dozens of exuberant teenagers, a frenetic pace, and Boncompagni’s hyper-kinetic direction, who directed with surgical precision, often speaking directly to the girls through earpieces. The show was a success and got renewed. In 1992, with its second season, the show moved to early afternoon on Italia 1, just in time to be seen after school, and Paolo Bonolis took over hosting duties, while the set transformed into a tropical island with pools, palm trees, and sand. The girls were no longer just extras: they became the absolute protagonists. In 1993 came what Ghergo calls «the great revolution»: Ambra Angiolini, «a very shy, introverted girl whom Boncompagni spotted immediately during a mass audition for Bulli e Pupe,» who not only became the host and face of the show but a pop phenomenon, adored by teenagers and disliked by adults. «She proved to be a true talent and has remained so,» says Ghergo. Through an earpiece («hosts hate it, it’s hard to speak with someone talking in your ear,» recalls Ghergo), Boncompagni fed her jokes, comments, even political statements. Famous is the episode in which Ambra declared, during an election campaign, that «God votes for Berlusconi» while «Satan votes for Occhetto,» sparking a media-political uproar. Ambra also became a singer: her song T’appartengo, written and produced by Boncompagni, topped the Italian charts and earned four platinum records, becoming the soundtrack of a generation.

As always, in Italy, you can’t have a bit of success without upsetting parent associations, Catholic groups, and assorted moralists. Non è la Rai became a target for all the usual suspects: Famiglia Cristiana, Telefono Azzurro, left-wing intellectuals, Umberto Eco, feminists, and child protection groups who accused it of sexualizing the girls, objectifying them with costumes that are harmless today but were then considered guilty of revealing the legs or belly buttons of the young protagonists. «We were unfazed by it,» says Ghergo, and indeed Boncompagni always responded with sarcasm, doubling down on the provocation: he wrote the theme song Affatto deluse in which the girls dressed as brides mock the accusations, and the song Non sono Lolita. And yet, the show’s production could not have been more harmless: «the girls had to follow strict rules: no showgirl makeup, they wore shorts under their skirts, parents were always present, and they had to dress as they would in their everyday lives,» recalls Ghergo. Meanwhile, while the moralists raged, hundreds of fans crowded outside the Safa Palatino studios to see the girls come out. «The amount of mail we received...,» Ghergo tells us. «Thousands and thousands of letters.» A real mass cult formed around the show, with magazines, calendars, CDs, official fan clubs, and merchandising. The program became so powerful that it influenced the fashion, language, and behavior of Italian teenagers. Girls all over Italy imitated the looks, dances, and even the speech patterns of the Non è la Rai stars. It was around this time that the iconic Eternit episode happened, now part of Italian trash TV lore. «I didn’t ask you anything, Maria Grazia» is perhaps only slightly less famous than «That branch of Lake Como that stretches south.» The show had jumped the shark: in 1995, after four seasons and hundreds of episodes, Boncompagni decided to end the program with a final, glossier, less provocative season. «It ended because the enthusiasm had faded,» Ghergo tells us. «He returned to Rai to develop Macao.» But years later, those same fundamental elements, that almost perfect formula of a content so light it nearly approached a vacuum, returned in the form of TikTok: the parallels between the two phenomena are striking.

Ambra Angiolini - T'appartengo (Live at Non è la RAI, 1994) pic.twitter.com/9ZjQDLtupE

— e (@muddytrap) February 22, 2018

The comparison between Non è la Rai and TikTok is not trivial: both are based on a non-scripted format that puts young people at the center, fueled by a tsunami of nonsense, irreverence, trash, and, in parallel, scandal. But it’s precisely in this chaotic mix that their cultural power arises—the ability to create generational phenomena that shake public opinion and enrage purists. In that September of 1991, Non è la Rai arrived like a bolt from the blue: a show antithetical to Rai, built on short segments, live broadcasts, hundreds of lip-syncing teenagers, call-in games, and a directing style that leaned into imperfection and improvisation. Just as today TikTok generates interest and engagement through short videos, often messy, with rapid editing, where nonsense becomes language and anyone can rise to viral fame—think of “very demure, very mindful” by Jools Lebron, for instance. Both encourage young people to participate, to co-create what we now call engagement, to make a show where the value lies not in structured content but in immediate performance. The beating heart is always the same: youth and collective participation. On TV, Boncompagni’s girls felt an excitement similar to that of Gen Z TikTokers, and the “bedrooms” of TikTok are the ancestors of the Safa Palatino studios: micro-fame spaces where a few seconds are enough to become visible, imitated, envied. Even today, a clumsy playback dance recalls the dancing chaos of those live morning broadcasts.

An important aspect that brings the two phenomena closer is their unscripted, irreverent, spontaneous nature. Boncompagni had understood that chaotic editing, aerial shots, mistakes, and strong emotions could generate a collective identity through their immediate realism. TikTok does the same: short videos, loud sounds, improvised choreographies, and “vernacular” speech become a style. The chaos is contained, but it represents the spoken language of a generation that doesn’t want to study, but to perform. It slides toward trash, true, but that very lack of value turns it into value—as we used to say: «nothingness elevated to art.» This “nothingness” has sparked moral panic that perfectly mirrors what happened back then. Today, TikTok is accused of creating addiction, attention disorders, self-esteem issues, of promoting the hyper-sexualization of teenage girls, with calls to protect minors from “absolute evil,” just like in past decades with rock’n’roll, anime, or video games. And yet, as scholars said: panic is cyclical, children seen as “innocent” must be protected, while media innovation becomes a scapegoat. For early ’90s TV it was irreverent lip-sync and screaming girls; for 2025 it’s the unfiltered visual algorithm.

Quando dite "io a 14 anni giocavo ancora con le bambole" per sottolineare la presunta spregiudicatezza delle ragazzine contemporanee rispetto alla vostra antica pudicizia mi chiedo se per caso avevate 14 anni nel 1920. No, perché 30 anni fa c'era Non è la Rai. Per dire.

— Letizia Pezzali (@letipezz) April 28, 2025

Moving on to the topic of subjectivity, both Non è la Rai and TikTok create a new form of visual social network: the former was a TV studio without an audience, a concentrate of adolescent energy. The latter is an infinite feed, personalized by an algorithm that builds a “flow experience” creating a sense of immersion—but both generate addiction and moments of collective ecstasy. On TV, people were glued to the screen to see Ambra declare «God votes for Berlusconi» or to watch her introduce Robbie Williams in studio; today, the equivalent is the video diary with millions of replays, memes, and political references in the endless scroll, where news becomes a microsecond and outrage becomes a viral function. Finally, both phenomena were producers of pop culture moments—sometimes fleeting, sometimes enduring—but always the product of a similar vehicle of superficiality and media exploitability. Both Boncompagni’s “non-educational” television and ByteDance’s mobile social TV marked the same trend: the shift from consuming structured content to a stream of fragments, from cinematic directing to domestic settings, from a “sanitized” audience to wild youth participation. In both cases, the show is built on influence, nonsense, trash, collective belonging, and the inevitable cultural scandal. The difference is that today we all see it, every day, in our pockets. A mix of performative recklessness, youthful protagonism, and moral scandal that defined a generational phenomenon.