We killed the pop music eras Both the fans and the music industry have ruined album rollouts

On Sunday night, Charli XCX posted a video on her TikTok profile where, with great honesty, she told her listeners that she doesn’t want to conclude the era of her album brat. She explained how, in recent days, the posts related to “brat summer 2.0” were ironic but also contained a hint of truth. The British artist has recently reflected a lot on the life cycle in music, especially when projects reach a high level of popularity in mainstream culture. Even though “brat” has been one of the keywords of 2024, Aitchison’s eighth album was released less than a year ago. Its rollout was certainly intense and sparked one of the most relevant moments of mania in pop music over the past ten years, blending elements of various subcultures (including the revival of the 2010s club culture and indie sleaze) and bringing them to the peak of pop. The album saw a deluxe version released a few days after the official launch and a remix album four months later, all within the first 365 days of brat. But why do we already feel so tired of it? Charli XCX’s case is not an isolated one. Since the end of the pandemic, there has been a constant rejection of “pop eras” as they were once conceived. Whereas in the past, radio stations would play singles from an album for almost two years after its release, now it seems that, after an initial moment of obsession, albums are quickly forgotten. What happened?

@charlixcx i’m not readyyyyyyyyyy!

original sound - Charli XCX

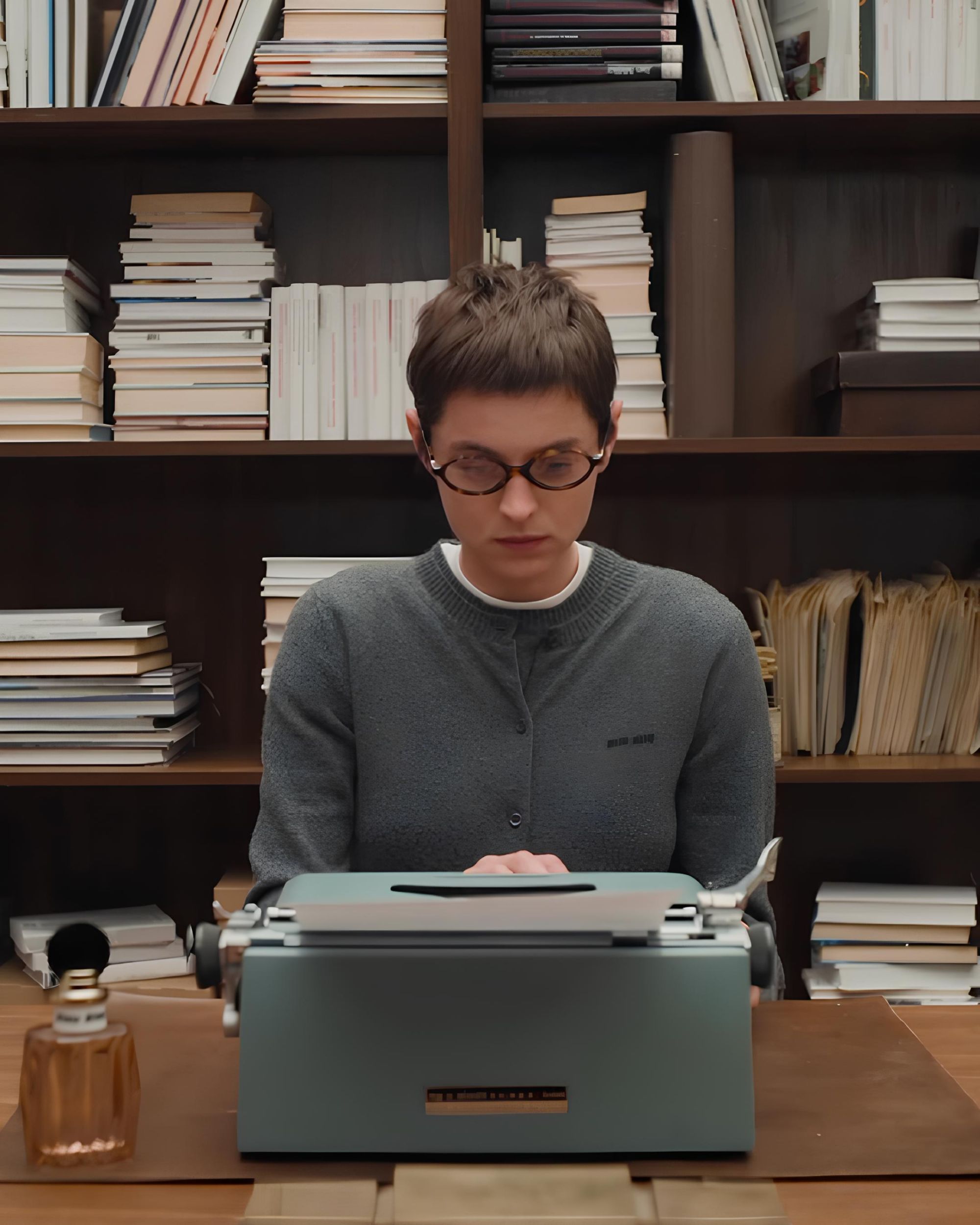

To fully understand the current disastrous state of pop marketing, we need to go back about ten years. The 2010s decade wasn’t just the pinnacle of pop music in terms of quality, but it also represented a bridge between the old physical music model and the modern era of streaming. Until a few years ago, an album’s success wasn’t measured solely by Spotify numbers but also by how many physical copies were sold. And what better way to promote an album than through singles? For years, singles were the lifeblood of a music project’s life cycle, just as important as touring. Take, for instance, 1989 by Taylor Swift, an album that critics and fans have called the “Pop Bible”: its era began with the pre-drop single “Shake It Off” in August 2014 and ended in early 2016 with the last single, “New Romantics”. During that era, seven singles were released from 1989, a number now unthinkable. Swift herself, in her latest project, released only two singles, one of which didn’t even have an official music video. Similarly, the Lemonade era of Beyoncé technically lasted from 2016 to 2019: between the visual album and headlining Coachella, promotion only ended in April 2019 with the release of the Netflix documentary dedicated to “Beychella”, along with a live album. Even for Beyoncé, there’s a clear radical difference between past projects and current ones: while for Lemonade, the artist promoted an entire visual album with five radio singles, for her current project, Cowboy Carter, she chose to promote only two pre-release radio singles, without any music videos.

bring back eras like these pic.twitter.com/Ol8MSlbpJO

— Bill (@KarmaIsAFad) January 11, 2025

As clearly pointed out by the user Flags12345 on the subreddit r/popheads, “streaming killed the post-album single”. The user explains that when an album drops on streaming platforms, the audience can immediately listen to every track, making it pointless to release additional singles for radio play, as the listeners have already consumed the songs. The result is that music “eras” are drastically shortened: the audience consumes the album in a weekend, record labels cash in on the initial streams, and quickly move on to the next project, abandoning anything that doesn’t go viral immediately. This trend confirms how pop marketing over the last five years has become a race solely focused on weekly charts, far from the long promotional cycles of the past. It’s no coincidence that today all artists release new music on Fridays, aiming to gather as many streams as possible over the weekend—when the audience has more free time—to secure a spot on the Billboard Hot 100 chart. This strategy has now saturated the market, as highlighted by YouTuber Camryn Suzanne, especially in 2024, a year marked by the simultaneous return of many big names in the pop industry. But how many of these projects have truly stuck in the collective memory? Suzanne argues that the lack of hype, combined with the absence of strong singles and an incisive marketing strategy, has led most projects to fade into oblivion within less than six months. The absence of a coherent artistic direction and a self-contained universe is slowly killing pop as a genre. Just look at the recent disaster of Katy Perry with her album 143, compared to the masterpiece of 2010, Teenage Dream.

I will forever be a hater of short songs. It's alright if there's one or two songs under 3 mins but you can't make a record with all songs being 2:30. Where is the bridge? Intro? Outro? Like pls make some music that's not made purely for radio

— :: :: (@pretty_infiniti) April 3, 2025

The obsession of record labels with going viral on TikTok has flipped the logic of pop itself. Today, songs are written with the first 15-30 seconds in mind, designed to dominate the For You Page, rather than to be listened to continuously, as Tyler, The Creator also pointed out in recent months after releasing his new album Chromakopia. On Reddit, several fans note that tracks under three minutes have become the norm, with bridges, outros, and third verses cut to maximize replays and, therefore, streams; many refer to this as “musical shrinkflation”, meaning songs feel like incomplete sketches but guarantee more hourly plays and cost less to produce. As a result, the album, once meant to give narrative cohesion to a project, is reduced to merely the frame for the lead single, and once the snippet has made its rounds on social media, the “era” fades away and the artist moves on to the next attempt at a trend. In the endless flow of playlists, listeners skip after just a few seconds if the chorus doesn’t hit immediately; consequently, songwriters and producers start tracks in medias res, cut bridges, and avoid any buildup that demands prolonged attention. In this ecosystem, the album becomes a luxury for nostalgics—a conceptual object that the majority no longer has the time or interest to experience from start to finish (as Beyoncé herself said a few years ago, “nobody makes albums anymore, they’re just projects”). As long as success is measured by the number of loops in a weekend, disposable micro-hits will prevail: fleeting tracks designed to die by Monday, when the algorithm is already demanding the next 90-second fix. R.I.P., dear album.