Did we stop believing in influencers? What is deinfluencing, the movement that wants to get rid of aggressive marketing

The era of the influencer is over. The era of influencers is coming to an end. Will the era of the influencer ever end? Something suggests that it will. It is unnecessary to explain who influencers are. They are personalities who are paid by brands to promote their products and persuade their followers to buy with their charisma. They used to be advocates of so-called trends, but today they are sounding boards rather than actual creators. Even though the absolute reign of influencers, brand deals and sponsored stories is undoubtedly Instagram, trends are now born on TikTok and are often 'micro' - i.e. developed within a niche for the audience within that niche and especially for a very short period of time. There are no product limitations. They range from make-up to publishing, from accessories to home care, with no limits. But some of these creators do not want to play the game anymore - and that's why the 'Deinfluencing' movement was born.

@laurenmorgillo #stitch with @eliseeatsplants like pls get help before you end up like me #deinfluencing original sound - LaurenMorgillo

Anti-consumerist aspirations emanating from global activism (think of Buy Nothing Day, launched back in 1995 but revived with renewed vigour and conviction in 2022) arrive on social media, where they are turning into hashtags with enormous follower counts, such as #nobuyyear2023 with 400 thousand views on TikTok and #anticonsumerism with 3 million, while #deinfluencing is even on its way with 50 million and shows no signs of stopping. Vice has registered a whole new anti-consumerist current typical of Gen Z in the so-called CoreCore current, to which Time has also dedicated space, a critical awareness among some users that 'too much is too much'. Deinfluencing aims to put a stop to this breathless cycle of trends, microtrends and viral products. It is a heterogeneous, spontaneously movement under which different types of content fall, from lists of products not to buy to the repetition of mottos and requests in videos not to be pushed into buying. The aim is to make viewers think about the trending phenomenon. Proponents of this movement include former 'influencers' who have come to their senses. Elise Maria says «If you were not around during the beauty Youtuber era, you may need to be warned: Think twice before buying products, especially if they have an expiry date, on the recommendation of people who are paid to sell them to you or have been gifted them. They may even be sincere and give you an honest review, but they could not care less about the cost to the consumer of these products. There will be another one next week, and then another. These people do not care.»

Trust your research, don't trust influencers.

— rahkai (@rahkainiskala) January 31, 2023

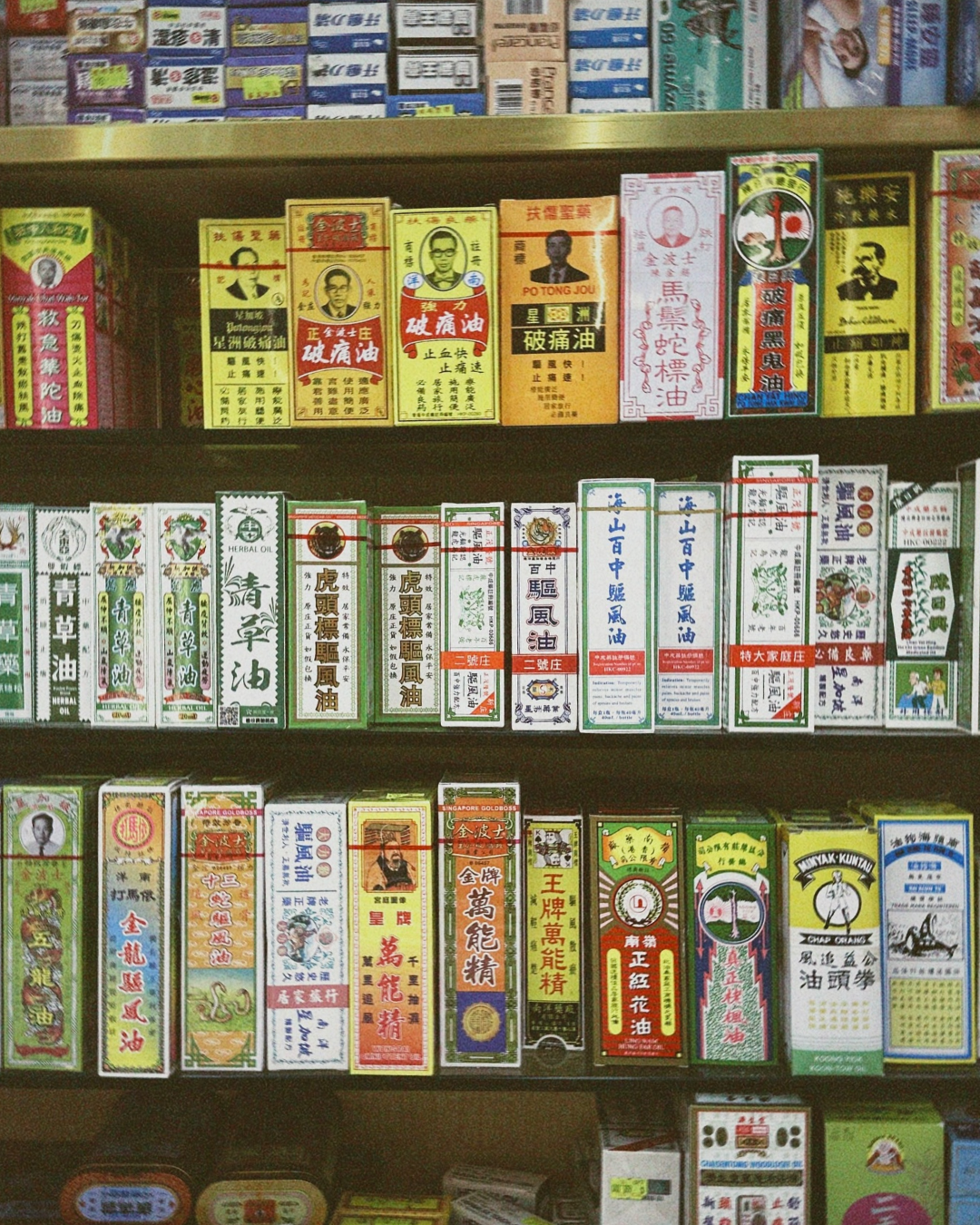

Lauren Morgillo affirms «I would love to get rid of TikTok. It makes me sick. I have a sickness. I have 5 tanning grounds that are the exact same colour, I have 7 blushes, no one needs 7 blushes. We should stop buying everything influencers try to sell us.» User Nidiaries also keeps a proper series on her profile titled 'Trends I did not buy this year even though the internet tried to convince me not to', in which she explains which products she did not buy and why. His lists seamlessly go from electronics to clothes, from Ugg Minis to Apple's AirPods Max, all of which have one thing in common: they have gone viral. Also in the whirlwind of microtrends to tackle are parachute trousers, which James Edward says will not last long. Also in the same boat are Oakley sports sunglasses, which James Edward says will go down long before summer.

The movement has no specific goal, but in its volatility it nevertheless manages to cast the general trend of overcompensation in a new light, without its glamorous façade. Deinfluencing makes it clear that there is something that could be called overcompensation that is in the same camp as burnout, with the effects of mental exhaustion and the difficulty of staying in social networks, with chronic dissatisfaction that comes from not keeping up with trends and aspirational models, with bursts of compulsive shopping that ultimately prove unsatisfying and therefore frustrating. Finally, the urge to compulsive and impulsive buying, especially when it involves large quantities of products purchased on e-commerce sites such as Shein or Wish, which offer cheap but also low-quality goods produced by exploited workers, is particularly demoralizing and insulting when it occurs in disregard of the difficulties faced by a large proportion of potential consumers. It is precisely on this anti-Shein and anti-Shein video hunt that Karishmaclimategirl, for example, has built her career as an anti-influencer by providing timely information about the exploitation of workers that this type of company systematically engages in.

me watching the deinfluencing trend videos on tiktok knowing i have never bought nor have the budget to buy all of these trendy makeup products impulsively

— 珠 (@necrobulist) February 1, 2023

One wonders, of course, what this means for influencers, for brands and for the platforms involved, such as TikTok and Instagram, which also base their revenues on it and which have changed accordingly (just think of the shop tab on Instagram). It would be naïve to think that this is the beginning of the end of an immense business and work that is likely to reinvent itself endlessly, taking new forms and becoming ever more insidious. In any case, deinfluencing appears as a warning light, a symptom of a general malaise (which Highsnobiety has aptly called 'consumer fatigue'), a red flag signalling that something is changing. According to Catalina Goanta, a business professor at Utrecht University who writes about it for The Conversation, one key to this change among content creators could and should be finding more transparency in how they communicate with their user base. And if you can avoid some impulse buys in the process, all the better.