What are the reactions to environmentalist demonstrations in museums? Between increasingly strict security measures and online criticism

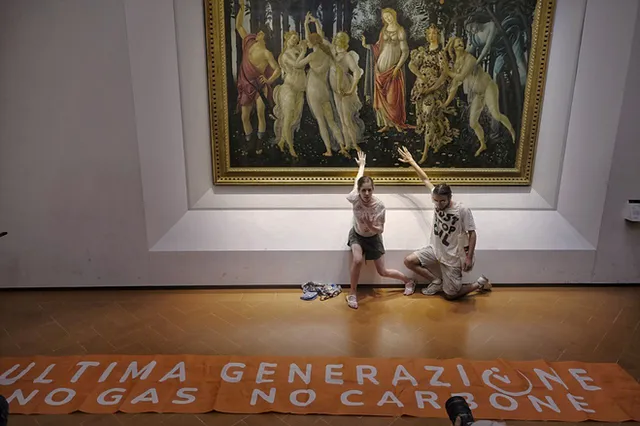

Recently, activists from the environmental group Ultima Generazione in Milan poured eight kilos of flour on a car painted by Andy Warhol that was on display at the Fabbrica del Vapore. In early November, the organization had called for vegetable soup to be poured on the glass of a Van Gogh work on display in Rome, and in recent months many of its members have repeatedly blocked the Grande Raccordo Anulare, one of the busiest streets in the capital. Similar gestures have been carried out in many other countries by organizations such as Just Stop Oil in the UK and Letzte Generation in Germany. In response to these events, several museums - large and small, in Europe and the US - have increased their security measures. But stopping the protests before they happen is more complicated than expected. Mainly because the actions are being carried out in ways that museum security officers are not used to, let alone trained to recognize and respond to in time. The Wall Street Journal reports that several museum facilities in the United States have turned to security agencies that work with airports and major sporting events to train their security officers. A Californian company that specializes in training security guards, Chameleon Associates, for example, has been hired by centres to send their plainclothes staff into exhibitions to behave without warning exactly as a demonstrator would - i.e. by walking around looking for cameras, rushing to the most famous paintings or communicating with their accomplices through gestures. The aim is to teach the guards in the galleries to recognize environmental demonstrations more quickly.

Put more simply, many museums are starting to control much more strictly what can be brought into the exhibitions. At the Galerie Barberini in Potsdam, for example, where two climate activists threw porridge at the glass of a Monet painting, visitors are no longer allowed to bring bags. Recently, guards at the Musée d'Orsay in Paris stopped a woman carrying a small bottle of soup and wearing a Just Stop Oil T-shirt. Museums are also working on adding glass protectors to paintings that do not yet have them. However, the likelihood of the protesters targeting works without this kind of protection seems very slim: «They want to attract attention, but they do not want to get into trouble. So far, what they are doing is not a serious crime if nothing is seriously damaged» a security consultant who worked at the Metropolitan Museum in New York told Artnet. Since no significant damage to artworks has been reported so far, other museums do not feel it is necessary to further strengthen security measures and over-guard galleries: «Museums should be open and safe spaces. In order not to turn them into high-security areas like airports, it is important that we find a balance between security measures that protect our visitors and the preservation of museums as places of freedom» said Christina Haak, deputy director of the National Museums in Berlin.

In all cases, the climate demonstrations in the galleries provoked very strong reactions, both online and among those present. During the initiative at Fabbrica del Vapore in Milan, an Ultima Generazione activist said to a woman who accused her of being deprived of Warhol's art: «In Italy we do not talk enough about climate change: I am much more afraid of it. Look what we have to do for the future of our country». During the demonstrations, activists are insulted, beaten and pushed, and there are countless hate comments on the internet. But according to the climate organizations, this is all 'part of the game': since the aim of the actions is to create conflict, people's anger is a positive sign. For the protesters, the protests are successful if they force millions of people to think about the climate crisis in one way or another, including by confronting the legitimacy or non-legitimacy of the radical actions. There is also growing frustration among environmental groups about the poor results of the peaceful demonstrations. Several organizations facing what they call the activists' dilemma - i.e. the choice between the peaceful but ignored or the attention-grabbing but more extreme approach - are now opting for the more radical path, with all the risks and difficulties that entails. The protesters claim that the time for moderation is over. Nevertheless, this is a "gentle" revolt: they are aware of the need to meet criticism with empathy, and without reacting to insults, they try to steer the discussion towards the environmentalists' cause. It is no coincidence that the political and philosophical reference that most guides the activists is Gandhi and the principle of non-violent struggle.

@eveningstandard Just Stop Oil say ‘We will not be stopped’ #juststopoil #activism #news #london #londonnews #astonmartin #uk #politics #fyp #climate #orange #environment original sound - Evening Standard

However, there is a danger that public awareness of the climate crisis does not emerge until it is too late. This is the reason why the most radical environmental policy positions are only held by a minority, especially in Northern Europe. In 2021, Swedish activist Andreas Malm published 'How to Blow Up a Pipeline', an essay advocating sabotage as a reactionary form of lack of awareness of the climate crisis on the part of governments and the population. Based on this assumption, Just Stop Oil damaged petrol pumps on London's M25 motorway in April last year; as a result, numerous tankers were blocked and at least 275 activists were arrested. In Italy, on the other hand, the most extreme initiatives were those of Extinction Rebellion and Climate Strike, which respectively blocked a bridge in Bologna and stormed Ciampino airport to stop private jets. All events that show that a form of radicalization can also take place for the cause of the environment, and that partly reflect the urgency with which institutions should address climate change and its serious consequences - which are already being felt today.