Undressing the man, a game of gender and identity Charlie Porter explores the concept of masculinity across the spectrum of Jean Paul Gaultier’s work

Masculinity is a question. What makes someone, or something masculine? Why? What happens when those assumptions are subverted? How does it make us feel? How close to the nerve can we sit? These questions have been in the work of Jean Paul Gaultier since the beginning. By the work of Jean Paul Gaultier, I don’t just mean his fashion output since his first collection in 1976. I mean his life’s work: at the age of 5, he turned his teddy bear Nana into his first model, fixing a cone bra to its chest. When Gaultier talks of Nana, he uses the pronoun “he”. The message is clear: from his first days, gender for Gaultier was a site of intransigence.

It is nearly seventy years since Gaultier made Nana the bear his cone bra. It’s forty years since Gaultier first introduced skirts for men, and thirty years since the debut of Le Male, the fragrance with the butch body as a bottle. And yet today, the word “masculinity” is more provocative than ever, particularly with LGBTQ+ rights coming under attack by governments and institutions around the world. We can look to Gaultier for clarity, insight and inspiration. I have been in the presence of Nana the bear. I saw him on display in November 2023 at MoMU, the fashion museum in Antwerp. It was so startling, to come across a teddy bear within a fashion exhibit. I took four photos of Nana on my phone, the bear and the bra, his hairiness juxtaposed with the supposed garment of femininity. Nana has a look on his face like he finds the whole thing hilarious. As a child, masculinity was dangerous for Gaultier. “The other kids at school often made fun of me,” he said in 1990, in the French magazine Actuel. “I didn’t embody the ultimate in masculinity, and it was a real nightmare for me to have to go to gym class or take part in soccer games – I hated it. When the teacher said, ‘Gaultier, you go on that side there,’ the other kids would howl in indignation. They called me ‘the sissy.’ That hurt, and it upset me.”

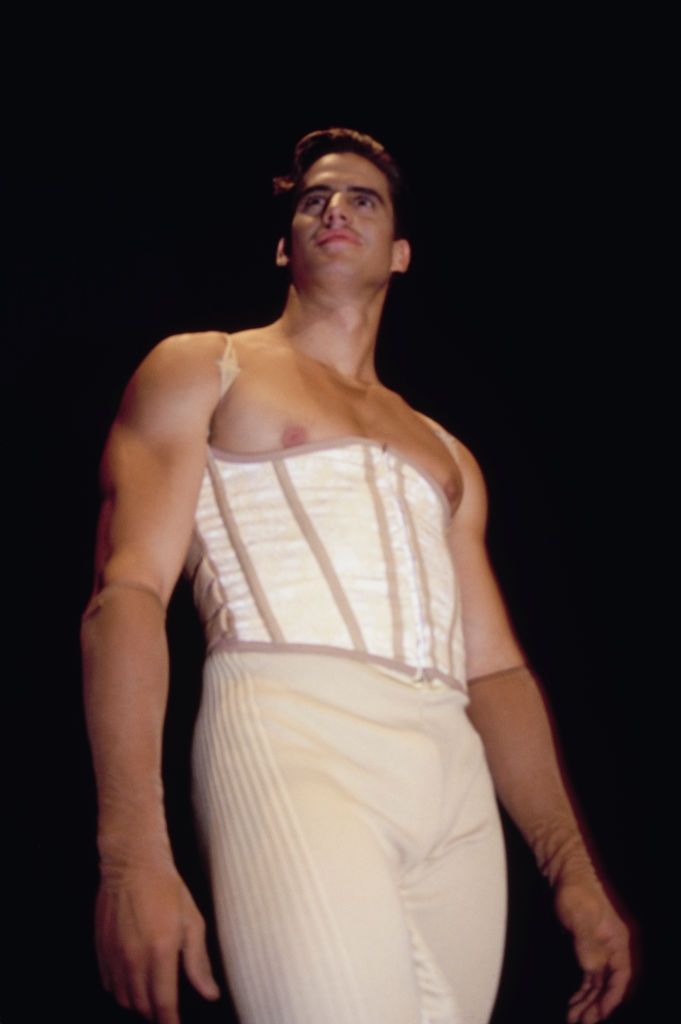

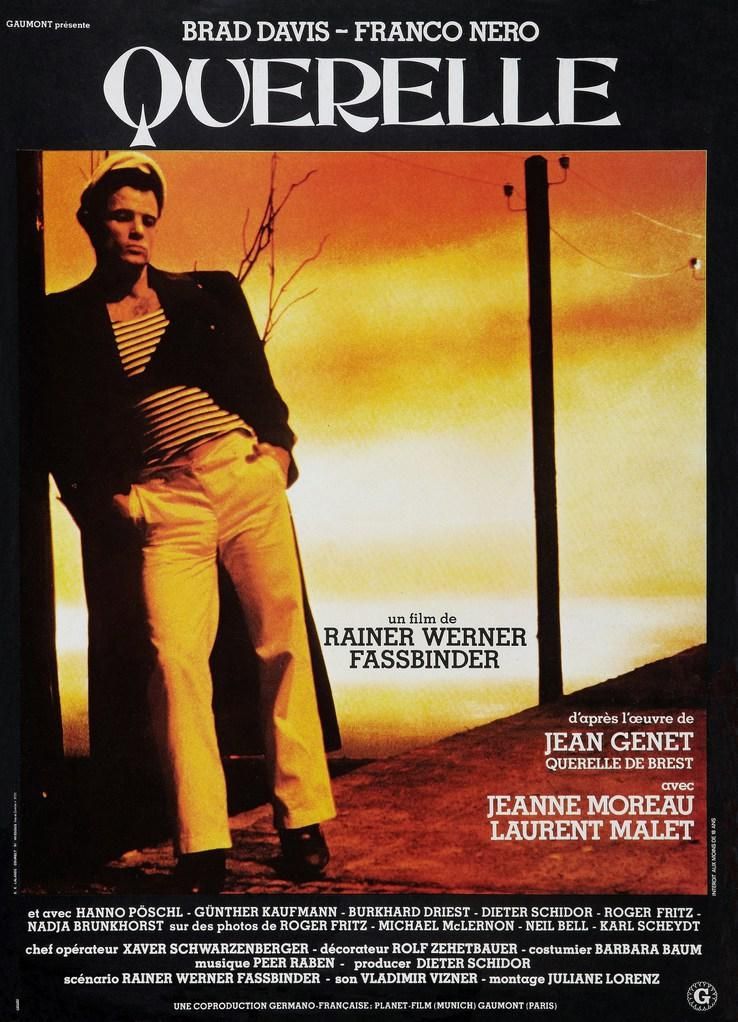

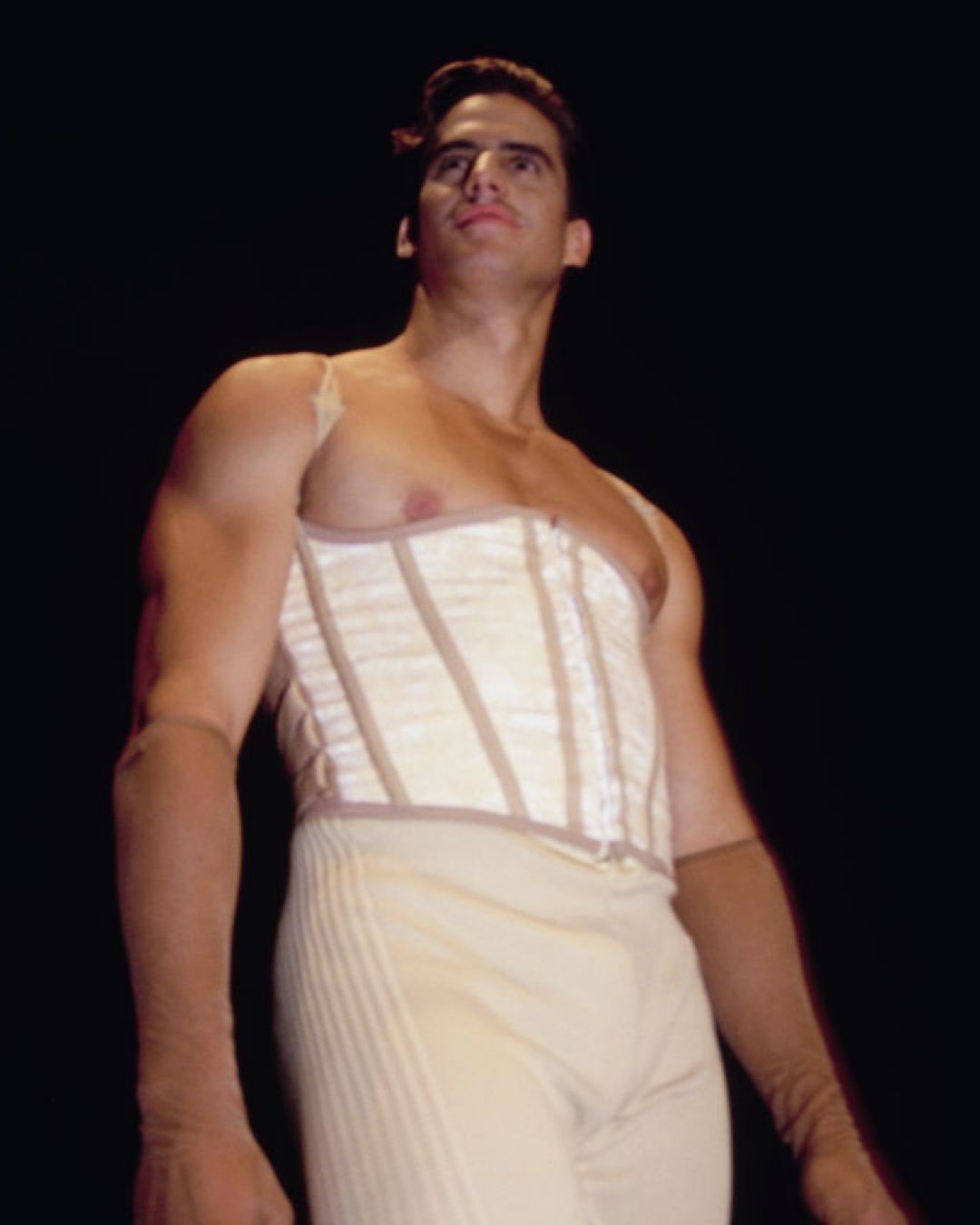

Gaultier’s response was self-protection. He retreated inside himself. “I just holed myself up in my own world,” he said. “I drew all the time. I didn’t have contact with other people.” In his own world, Gaultier self-educated himself in fashion through magazines. His early experiences of masculinity were perilous, yet also shaped him: his rejection of the binary created the space within which his fashion foundations could be formed. The year 1982 was crucial for Gaultier’s understanding of masculinity. It was the year that R. W. Fassbinder’s film Querelle was released, appearing in French cinemas on 8 September, three months after the director’s death. To watch Querelle now is like watching inside Gaultier’s brain, so deeply did it inspire him. It’s there from the opening shot: muscled, butch, sweating sailors, crammed tight together, at work on a stage-set boat deck, with no pretence that it’s sea, the lighting a relentless yellow of permanent sunset. The film is an adaptation of Jean Genet’s 1947 novel Querelle de Brest, a story of beauty and violence, its queerness expressed through toughness. Fassbinder’s film turns the masculine characters into queer iconoclasts, channelled through the impossible beauty of its star, Brad Davis. Masculinity is presented as an aesthetic, a visual language of strength cut by irrepressible vulnerability.

For Gaultier, the film was like a key to unlock the door of masculinity. It is as if Querelle put masculinity into play, becoming a site of interrogation. This questioning of masculinity was vividly apparent in a women’s collection Gaultier presented a month after the film’s debut. His celebrated spring/summer ’83 women’s collection, titled Dada, was a crucial turning point. Many of the looks were overtly feminine, such as slips and corsets. The collection featured the now-famous corset dress, as well as a corset jumpsuit, with the laced body attached to some slim pants, with corset lacing detail at the ankle. But it wasn’t just a collection of femininity. Gaultier played with masculinity in womenswear, particularly in tailoring. He took the classic tuxedo jacket, then elongated it, creating a tailored button-front dress. The Dada collection was shown in October 1982, for delivery to stores in spring 1983. That season, New York boutique Dianne B. commissioned artist Cindy Sherman to create that season’s advertising imagery. These artist campaigns were a signature of the store, appearing in Andy Warhol’s Interview magazine: other artists who made similar campaigns include Robert Mapplethorpe, Peter Hujar and David Wojnarowicz.

For her campaign, Cindy Sherman selected various new season’s pieces that would be stocked in the store, then photographed herself in them, taking on a role in front of the camera. In one image, she wears the Jean Paul Gaultier corset jumpsuit. She faces the camera and makes a mocking pout, as if to poke fun at the presumed poses of fashion. Then, in another image, Sherman wears the Jean Paul Gaultier tuxedo dress. In this image, her head is down, her fists in balls, as if in rage at masculinity. They have become some of Sherman’s most celebrated works, the power of Gaultier’s investigation of gendered garments in the Dada collection still resonant today. It was in his third menswear collection, for spring/summer 1985, that Gaultier declared his greatest provocation against masculinity. The collection was titled And God Created Man, and featured pairs of trousers to which had been attached a wrap, like a skirt. Gaultier stated the design was based on the aprons worn by waiters in Parisian bistros. The shockwaves of the collection went round the world. In a New York Times feature titled “Skirts for Men? Yes and No,” Gaultier told writer John Duka, “Wearing a skirt doesn’t mean you’re not masculine. Masculinity doesn’t come from clothes. It comes from something inside you. Men and women can wear the same clothes and still be men and women. It’s fun.”

Some retailers were less amused. “They’re revolting,” said Selma Weiser, the owner of boutique Charivari. “No, I hate the word ‘revolting’. Skirts for men are disgusting.” Customers around the world disagreed. That season, Gaultier sold 3,000 men’s skirts. It is extraordinary, the commotion caused by a piece of fabric. The crucial word here is “fun”: Gaultier was playful in his approach. He was serious in his mission, saying to another New York Times reporter, Patricia McColl, that “it just seems to me that attitudes toward men’s wear have to be re-examined”. But his provocations came with a lightness, with humour and with charm. In his menswear, Gaultier was an encourager, an enabler. Skirts soon became part of the Gaultier masculine signature, alongside Breton sweaters and strong-shouldered tailoring with a fitted waist. In 1985, Gaultier was invited to the Élysée Palace to meet the French president, François Mitterrand. Gaultier wore a Breton sweater under a double-breasted jacket. With him was his partner in both life and business, Francis Menuge. Menuge was wearing a pinstriped double-breasted jacket with strong shoulders, matched with Gaultier’s skirt-trouser from the SS85 collection. It is a beautiful image, the two of them in this most formal of settings, dressed on their own terms, their own expression of their masculinity.

In 1990, Francis Menuge died of AIDS-related causes. The fashion critic Suzy Menkes wrote that “the designer’s emotional compass was altered by the death in 1990 of his partner Francis Menuge.” It is hard now to imagine the homophobia and suppression of the time, how little space society, including the fashion industry, gave for grieving, or even acknowledging, those who had died from AIDS. I write of Menuge’s death here, in this essay about masculinity, because of vulnerability. Gaultier’s designs for men, with their mix of toughness and softness, recognised that vulnerability is a key component of masculinity. Menuge’s death caused Gaultier to change his approach to work. In 1993, he became co-presenter of the TV show Eurotrash, which poked fun at sex, sexuality, masculinity and gender. Gaultier has said that appearing on the show helped him with his grief, helped him take his mind somewhere else. In the same year, Gaultier launched his first fragrance, Classique, confronting gender by packaging the scent in a bottle the shape of an idealised female body.

Its foil was Le Male, the men’s fragrance introduced two years later. It is extraordinary, and radical, that this masculine vulnerability should then fuel one of the most successful fragrances of the past thirty years. Le Male was created for Jean Paul Gaultier by Francis Kurkdjian, a perfumer who, at the time, was 25 years old. “Le Male reflects the sensitive side of men,” said Kurkdjian, “a facet rarely exploited in perfumery.” The bottle for Le Male is butch: a muscled body covered in Breton stripes. The juice inside is sensual. From the beginning, campaigns for Le Male have been pure Querelle, playing out masculine vulnerability. This is the humanity that Gaultier represents in his work, the compassion, the sensitivity, the questioning. This is what Gaultier can teach us about masculinity, if only we are willing to learn.