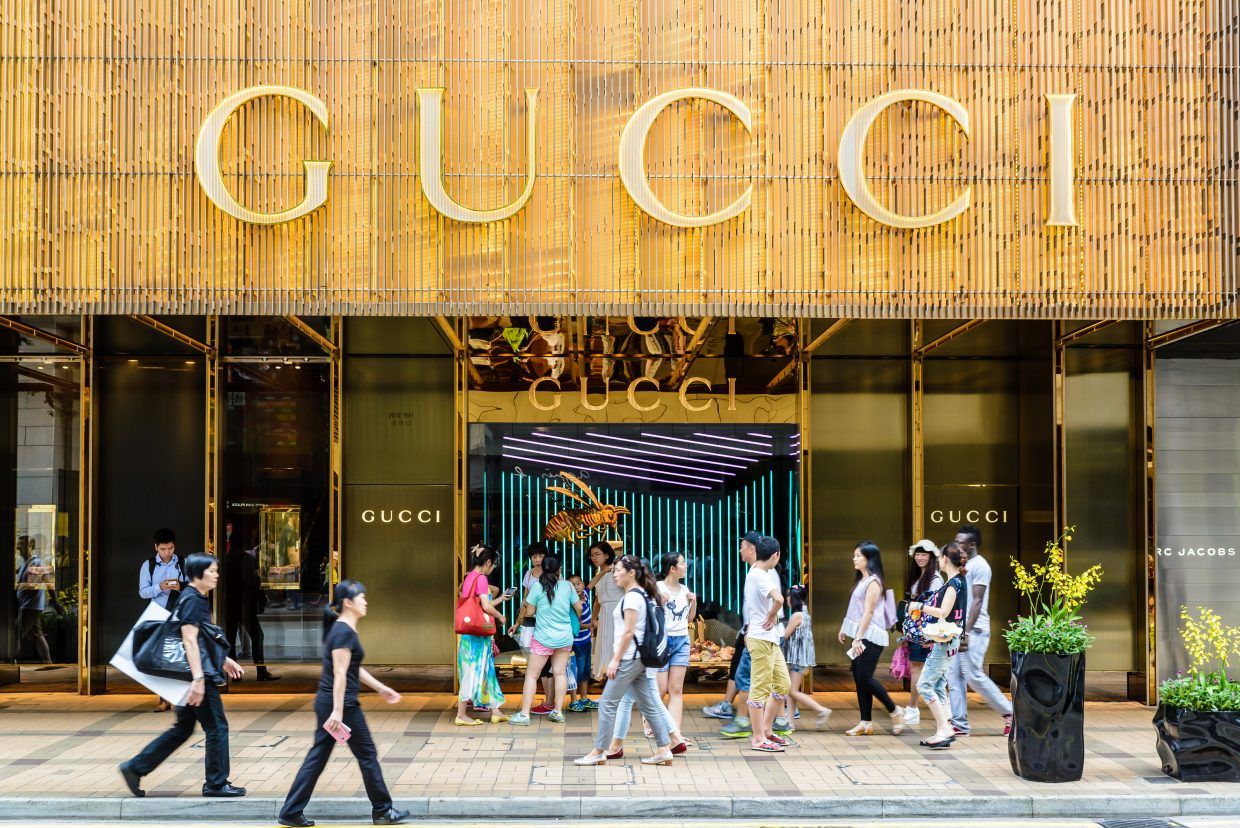

Will revenge spending restart the luxury market? China has returned to spending more than before after reopening, it's not said that the same will happen in Europe

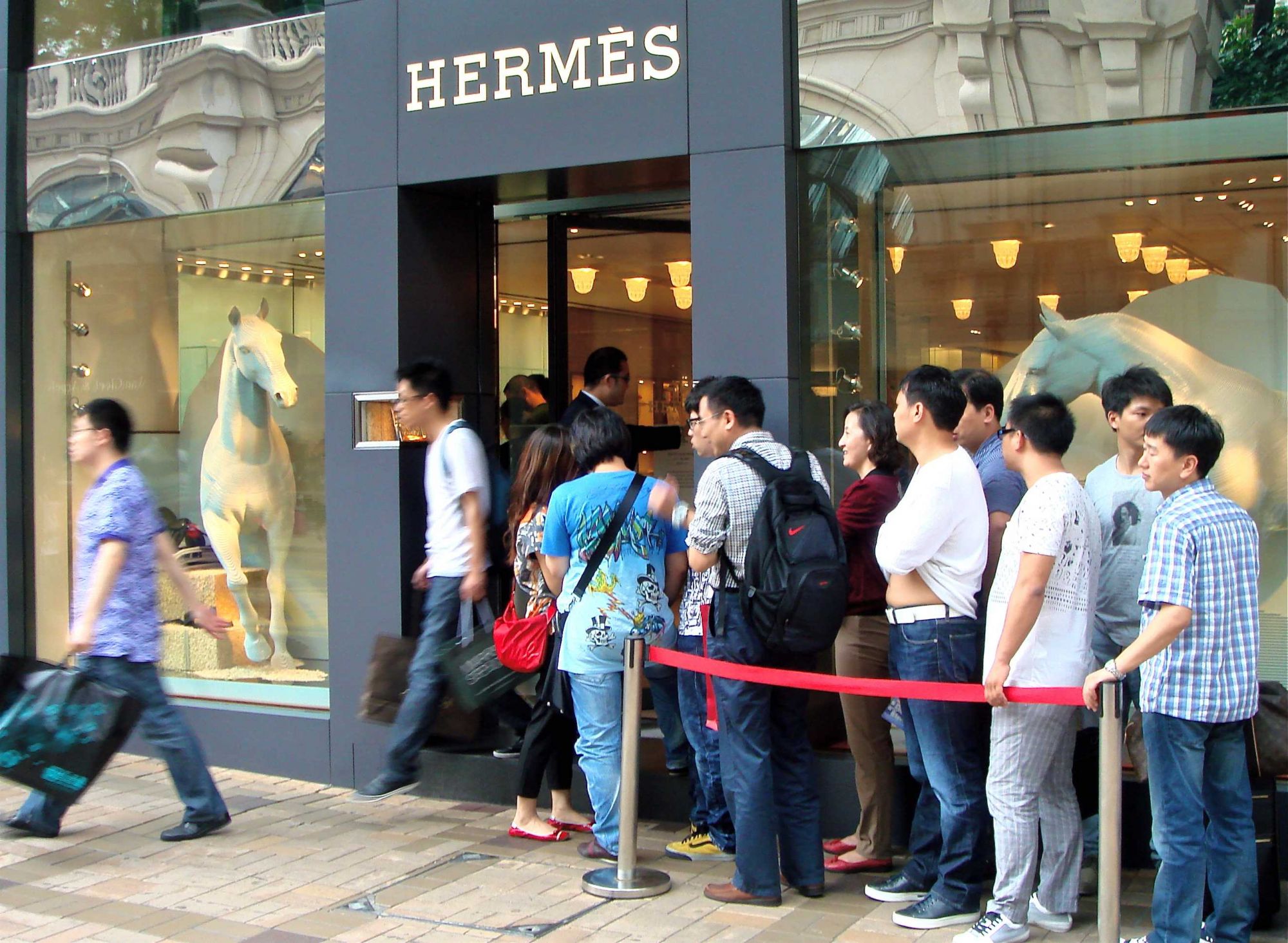

According to a report by WWD, on the day of last Saturday alone, in one of the very first days after the reopening, the Hermès boutique in Guangzhou hauled a total of 2.7 million dollars. This is also a very high figure compared to normal standards, which has opened up the discussion about how the luxury market and its consumers will react to the end of the lockdown. After the SARS outbreak in China caused a similar period of decline in sales in 2003, the end of the epidemic saw the public spend far more than before - a phenomenon called "revenge spending" that occurs when a consumer, after a moment of forced savings, spends "for revenge" more than normal. Many analyst firms are already trying to sort through the first data that emerged from the Chinese reopening to predict whether revenge spending will be the dominant behavior even in the West to breathe new life into an industry that is likely to pay a very high price. Experts have conflicting views on post-crisis consumer behaviour: some believe it won't change anything others argue that the crisis will be a major psychological shock and will radically change drives in luxury shopping.

However, Chinese data is unlikely to be a reliable prediction for the whole world as consumer attitudes in China are very different from Europe: just think of how, according to a report by The Business of Fashion, China was responsible for half the growth of the primary luxury market between 2012 and 2018 continuing to grow from year to year. Secondly, the economic crisis that is due to end the epidemic, which makes it difficult to think that even in Europe there may be intense forms of revenge spending such as those seen in China. But not even in the East did the phenomenon occur in the same way as in 2003, and for a simple reason: its premises have changed.

A report on the attitude of Chinese consumers by Jing Daily ranked three orders of issues related to revenge spending. The first is the awakening of the consciences of younger consumers who, in a health crisis over, and against the background of a thriving economy but in the midst of a slowdown and in the midst of the trade war, would be less inclined to spend on essential luxury goods and opt for more conscious consumption. The second issue concerns sustainability, with a marked preference given by consumers to sustainable brands and supported by social statistics that speak of a very strong increase in online discussions centered on the problems of environmental conservation and ecology. The third issue is nationalistic: a new social sensitivity pushes Chinese consumers to support native brands both as covered in an abandoned heritage in favor of European luxury products, and in the act of solidarity with small independent brands that, unlike commercial titans such as LVMH or Kering, have been crushed by this crisis.

This is precisely what Eugene Rabkin focuses on, which in an article published in The Business of Fashion gives a skeptical view of a radical change in the fashion industry:

“We have conditioned millions of consumers to need a near-constant supply of cheap clothing to feel cool. [...] LResearch shows that despite their stated concerns for sustainability, the majority of Millennials do not shop this way, because sustainable clothes are expensive compared to fast fashion.[...] CWhat may well be missing from the landscape? All those smaller, slower, independent labels [...]. This tragedy, more than enlightened consumers, will shape the post-pandemic fashion world.”.

A vision that may sound cynical but could be realistic. Especially in highlighting how the fashion system in its desire to spread its myth and push the accelerator of marketing has created a huge segment of consumers who want to live the "beautiful dream" of creative directors but can not access products whose prices are anything but democratic and that for this they turn to fast fashion. The vicious circle thus started hardly takes into account the sustainability and durability of the products: to count is the novelty, the ability to replicate the style of a certain brand at a fifth of the price and ultimately the thrill of consumption.

The uncertainty of the future is also given by the fact that the changes brought by the pandemic are as economical as psychological: when consumer psychology changes, shopping habits change. For this reason, the Jing Daily report emphasizes the importance that, in the post-coronavirus world, brands will have to give to communication and interact with an audience more attentive to the environment and more experienced by the economic difficulties caused by the pandemic.