The origins of Harajuku street style: interview with Shoichi Aoki FRUiTS magazine founder recounts the style that defined Y2K in Japan

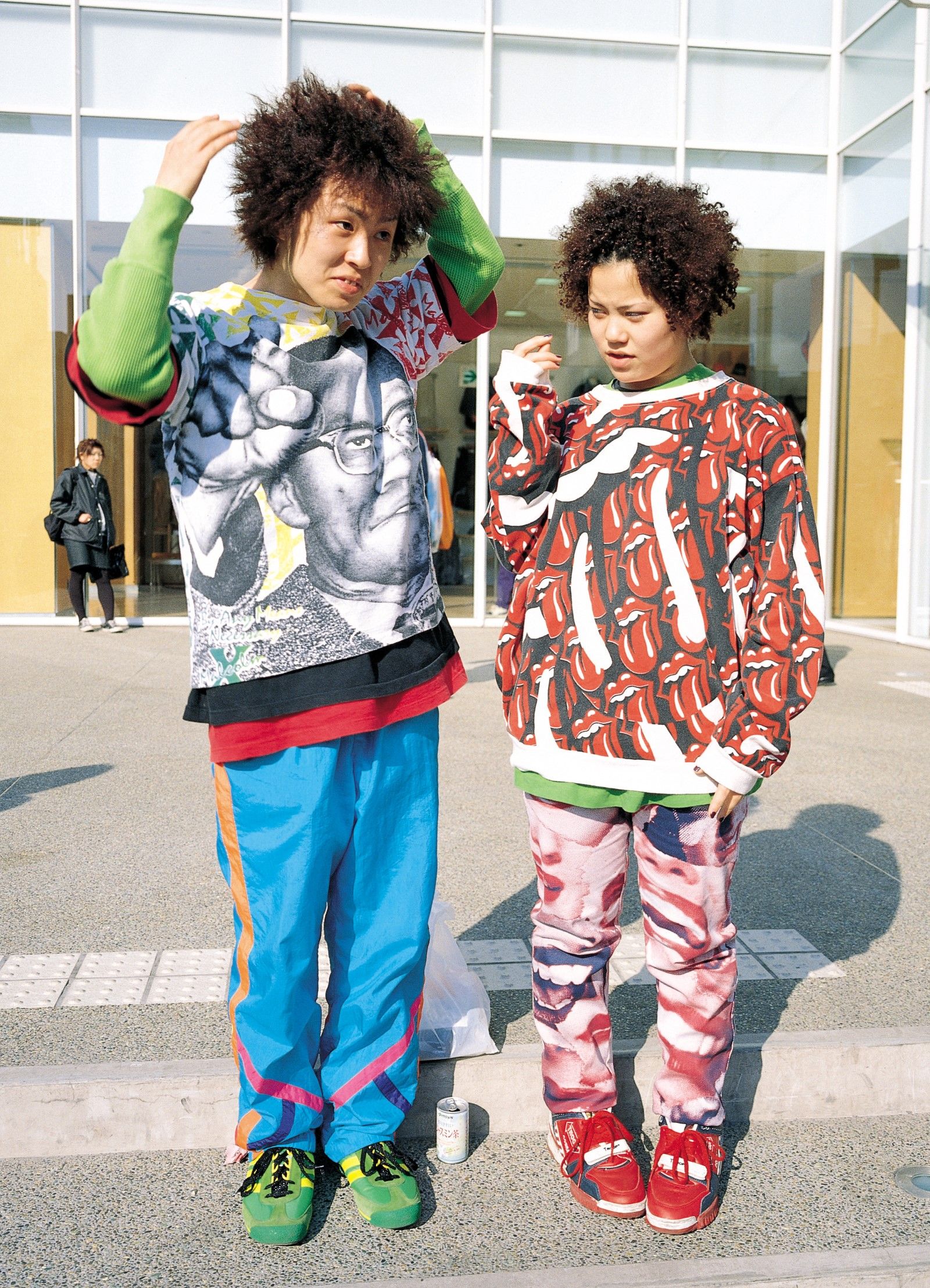

When Instagram still didn't exist and fashion publications told of a muffled and distant world, of fine Parisian salons and Milanese catwalks, there was little space that publishing gave to street fashion. In the 1990s, Shoichi Aoki was one of the first to document the street aesthetics of Tokyo's Harajuku district, narrating it in the pages of the iconic FRUiTS magazine and acting as an ambassador for Japanese streetwear around the world. The Harajuku style was beyond definition: kitsch, colorful, bizarre, unlike anything you'd ever seen before. And the greatest value of FRUiTS magazine was to be a real chronicle of the life of a young and dynamic neighborhood in Japan of that era. It was a cheerful, young magazine that celebrated the local culture by elevating it to the same status as the inaccessible world of couture and, in many ways, foreshadowed that self-expression that would come with Instagram decades later.

Here's the translation of the text into English without altering the HTML code: ```html

After twenty years and 233 issues, FRUiTS ceased publication because, according to Aoki himself, "there are no more cool kids to photograph." But a few years later, the Englishman Christopher Tordoff breathed new life into the magazine's photographic archives with the Instagram account @fruits_magazine_archives. The success of the account, which Shoichi Aoki himself contributed to, rekindled the myth of the great photographer in the collective memory: today, the photographer is busy bringing modern Tokyo street style to Instagram through the official account @fruitsmag, presenting the digital re-editions of his historic shots online through e-book sales and the revival of STREET Magazine, another revival of an editorial project, and signing projects like the lookbook for the very recent collaboration of Vivienne Westwood and Palace. Some time ago, nss magazine interviewed both Aoki and Tordoff to learn about the history of FRUiTS magazine and the Harajuku district in the '90s, and how both of them thought of translating this visual narrative into the era of digital media. Shoichi Aoki also curated an exclusive selection of images for nss magazine from the magazine's original archives on the occasion of the interview.

```

SHOICHI AOKI

Harajuku style is a very recognizable aesthetic but also a very site-specific one. How would you explain it to a foreigner that is seeing it for the first time?

Harajuku style is very community driven, evolving from shared ideas and influences. Tokyo is unique, in that it has specific areas where its fashion trends would not be seen anywhere else in the region. For example, Ginza and Aoyama are both well known for high end fashion, where brands like Gucci and Chanel thrive, whereas Harajuku has embraced a kind of “dirty”, yet kitch aesthetic. You would never see Harajuku style on the streets of Ginza no more than you would see Ginza styles in Harajuku.

Was there a phenomenon or a brand that jump-started the Harajuku aesthetic? How was it born?

Harajuku style began around 1996, as far as I can remember. Before that, Japanese fashion brand Comme des Garçons and designer Yohji Yamamoto were the gods of fashion with their minimalist aesthetic and mono colour pallets. This was known as the "DC Boom” and lasted around 15-20 years, before interest began to fade. Then, British fashion brands like Vivian Westwood and Christopher Nemeth started to gain followers, which then opened the way for the Harajuku style we know today, thanks to the rise of exciting young Japanese designers, vintage stores and an economic attitude for cheap items.

Why did you choose to name your magazine FRUiTS?

For me, fruit like oranges and strawberries etc. captured the style, colors and attitude seen in Harajuku at the time. It reminded me of a freshness you can only find in fruit, a style that was poison free, with a refreshing sweetness. A style that could pass as vegan friendly! That is why I chose FRUiTS, the perfect representation of 90’s Harajuku.

Japanese streetwear is often, and rightly so, talked about as a reality in itself, a separeted genre of streetwear. What’s the main difference between European/American and Japanese streetwear?

It all comes down to history and location. European and American fashion has a long history of evolving styles and looks, whereas Japan, with our isolation to the world began to express these styles much later. It wasn’t until around the 1950’s that Western fashion was introduced to Japan, where demand exceeded supply. With so much history of fashion now available, the people of Japan consumed it all at once, giving way to a unique attitude and look that could only be seen as a result of this “catch up”. We are seeing a similar process in China, thanks to the rise of global interconnectivity. It’s actually quite liberating and free to pick and choose styles from history and combine them to create the unique looks that eventually evolved into the Japanese streetwear we see today.

What is the legacy of Harajuku style and how did it impact modern fashion? And where is Japanese streetwear heading to today?

I think it was Karl Lagerfeld who said “all fashion designers today are influenced by Harajuku”. “Decora” fashion is perhaps Harajuku’s most famous legacy as it has now been exported around the world as the “face” of Harajuku fashion. Where is Harajuku style heading? Up until recently, Harajuku fashion had become quite lazy. It had lost its uniqueness by essentially copying itself. Thankfully, designers Demna Gvasalia and Virgil Abloh broke the deadlock and helped bring around change, with Chinese tourists embracing it first. As a result, Harajuku is becoming interesting again. I feel that we’re now at a very interesting point where these new designers are on the cusp of giving birth to a new and exciting trend that will once again put Harajuku back on the fashion map.

Is there a future for FRUiTS Magazine? Are you planning a revival?

Yes, thanks to the changing face of Harajuku, we now feel it’s time to bring FRUiTS back. We are currently hard at work in creating a media presence that will both effectively tell the story of contemporary Harajuku, while retaining the same attitude that made FRUiTS such a success in the 90’s.

CHRISTOPHER TORDOFF

Tell us the story of the first time you laid your eyes on FRUiTS Magazine. How did it happen?

I was introduced to FRUiTS when Channel 4 (UK) aired a Japanese pop culture season way back in the 90’s. Seeing the street fashion of Harajuku for the first time had a huge impact on me, especially as a teenager expressing myself through Punk and New Wave. Though soon my interests inevitably drifted as I got older.

Your Instagram archive is very nostalgic of the ‘90s Tokyo. What element of that time and place and of Harajuku aesthetic resonates so much with you?

The 1990’s were a very special time for me, they were my hallowed teenage years! Creativity was off the charts with bold fashion trends and the music scene had a real and unmistakable identity not seen since I think. There was a genuine sense of hope for my generation and a positivity that fed into all aspects of creativity. Harajuku was the nucleus of this positive creative boom in Japan, and much like the punk revolution of the late 70’s, it was a time for a generation of kids to shout out who they are and why they’re here.

What was the first question you wanted to ask Mr. Aoki when you met him the first time?

I’ve worked in the publishing industry for a long time so my chief question was “where can FRUiTS go from here?” as a publishing business. From there, our conversation inevitably drifted to social media and the role it plays in documenting the changing face of fashion today. As a result, we decided to “road test” the Instagram generation’s reaction to the archive photos with @fruits_magazine_archives to see if Aoki-san’s original vision is still as fresh and engaging today as it was in the 90’s. Thankfully it is, more so than ever.

Do you think that Instagram could become a suitable platform for a new incarnation of FRUiTS Magazine?

Instagram is a very useful tool in raising awareness, but not so effective in telling the story of Harajuku. FRUiTS isn’t just a collection of street fashion photos, it’s a live narrative of the rapidly changing fashion landscape of Harajuku, so the platform must be able to convey that narrative as effective as the print magazine did. But Instagram is integral to this mission, so the FRUiTS Insta accounts won’t be going anywhere soon.

You talked with Dazed about “the ethos of DIY fashion”. Do you think that that type of ethos has a space on the fashion scene today? And if so, which space is it?

John Galliano said “The joy of dressing is an art” and I guess all artists begin by experimenting. Fashion is expression and the more we want to express ourselves, the more fashion becomes noticeable. This is where “the ethos of DIY fashion” plays its part. It’s thanks to this mindset that the fashion world, from high to low, can function. An evolving process that starts in the street, then is picked up by the catwalk and back to the street again. It’s a fascinating symbiosis.

From a foreigner’s point of view, how did Tokyo change from the ‘90s to now? How did you think the culture shifted?

I think Tokyo, particularly Harajuku became a victim of its own success. Thanks to magazines like FRUiTS and KERA, the world discovered and embraced the styles of Japanese youth subculture and this global popularity fed back into Harajuku to the point of over-saturation. Harajuku became a kind of parody of itself. I lived in London for many years and saw an almost identical transformation happen to Camden Town. Thankfully we are now seeing a resurgence of unique styles with new designers and different attitudes. It all comes back to this evolution and symbiosis that makes fashion so addictive!