Supreme and "Kids" The 90's New York skate culture

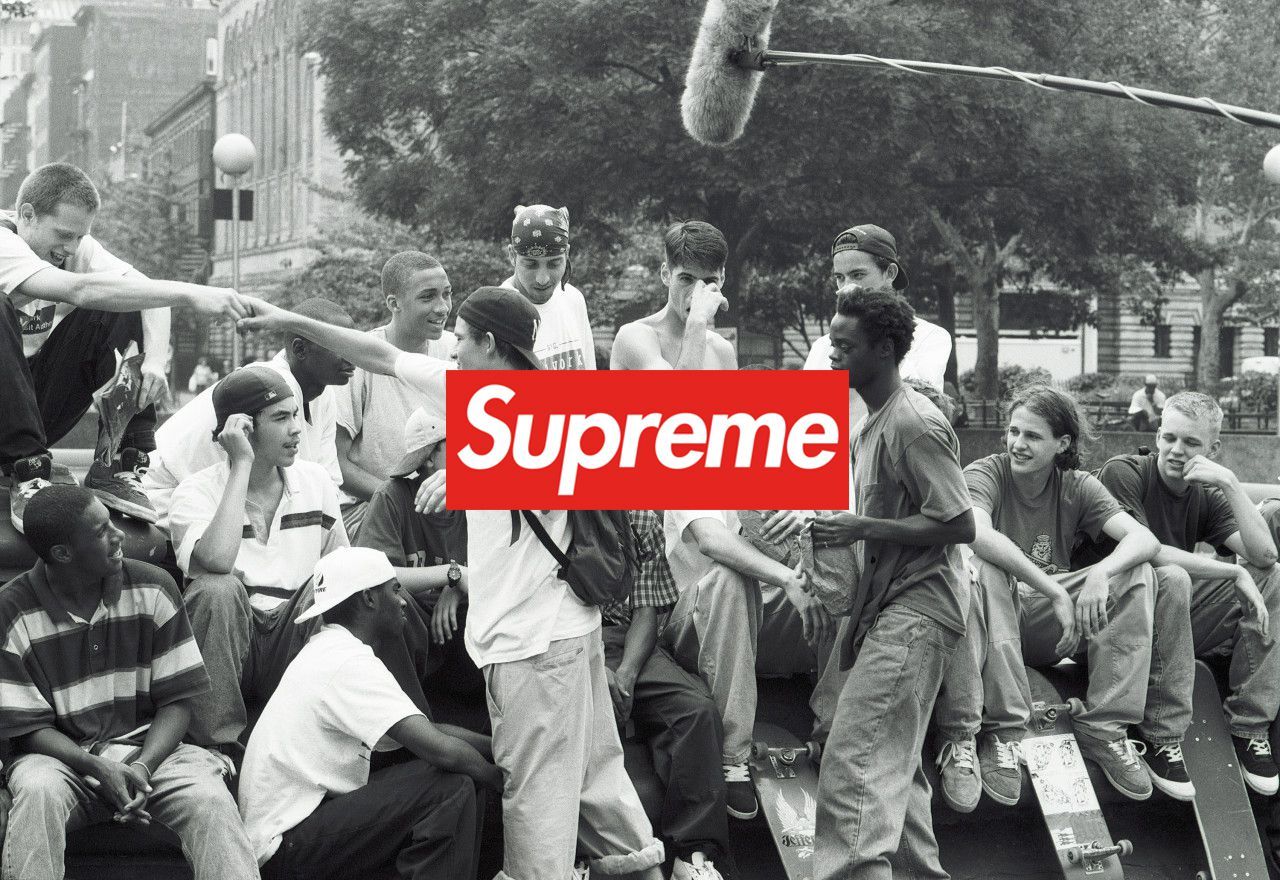

"Daddy Never Understood" by Deluxx Folk Implosion, the song that opens one of the most controversial movies of the 90s, "Kids", written by Harmony Korine (from his pen will arrive other films destined to destabilize criticism and public opinion as "Gummo" of 1997, of which he will also be director and "Ken Park" of 2002), directed by American photographer and director Larry Clark, (whose debut it will mark as a director) and milestone of independent American cinema , is a paean to adolescent anger. Because the theme that I chose to tell the story of Supreme's origins in a different way is anger, which permeated the New York skate culture of the 1990s, captured perfectly in the 1995 film "Kids". The two stories are one inside the other: both are an expression of the New York skate counter-culture of those years and fully represent their aesthetics.

The issue was all about being pissed off.

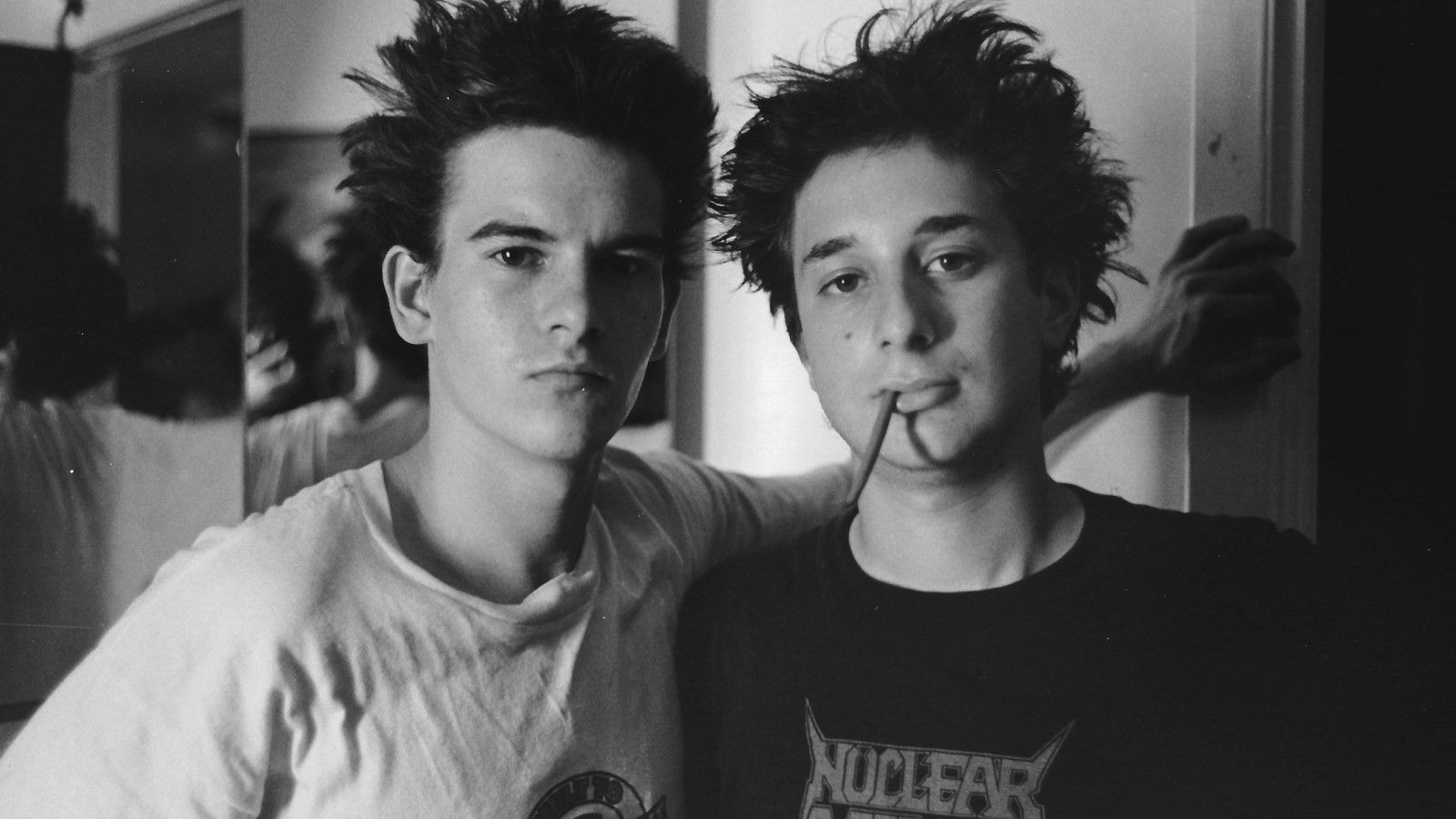

Harmony Korine was pissed off, a 19 year old and skater in Washington Square in a face-changing New York in 1994 (the Washington Skate Park was the heart of New York skateboarding). Rudolph Giuliani has just become mayor of the Big Apple who has focused his entire electoral campaign on the "cleanliness" of the micro-crime that had held New York hostage throughout the 1980s. There was a real crackdown that particularly affected those who made the road their own home. I'm talking about those guys who spent their days sitting on the pavement drinking, smoking weed and skating. Harmony Korine defines the New York skate scene of those years as "very angry".

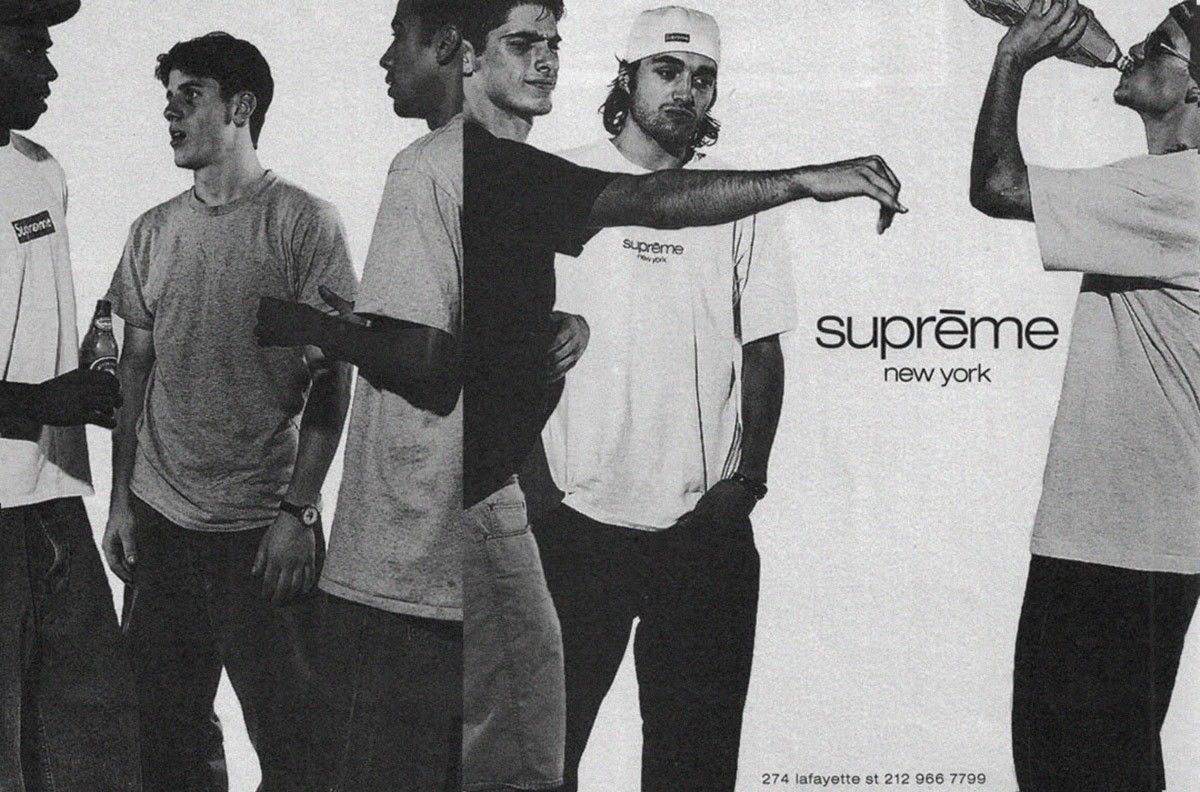

Aaron Bondaroff was pissed off - or as he was defined in the series of photographs dedicated to the most representative characters of the Big Apple Marvels in New York, "A-ron the Downtown Don." While by Vogue he was addressed as the "quintessence of the New Yorker who thanks to his work has influenced and directed the Downtown subculture "- for years the unofficial face of Supreme and one of the guys who "worked, spent time and even lived there "in the store at 274 Lafayette St, between Prince and Houston.

And so did all the others who together with him had made Lafayette their home. They skated and played soccer or whiffle-game (a variant of baseball that is played with a pitted ball) in the traffic, and never left the neighborhood. It was not a store like the others, it was "the last social club" left standing in Little Italy, Downtown, Manhattan. It wasn't suitable for everyone, in fact, the guys who worked there had created a business model that, despite the rough and rude manners, worked because the next day twice as many customers arrived. Whoever entered the shop could not for any reason touch the exhibited goods, if you did you would be thrown out, and outside you would find the others who in the meantime skated and in turn treated you even worse; you were a stranger in a territory that didn't belong to you and in which nobody wanted you; if you weren't one of them. They were the original Supreme skateboarding team. That was their way of being in the world. That way of being in the world that Larry Clark wanted to tell.

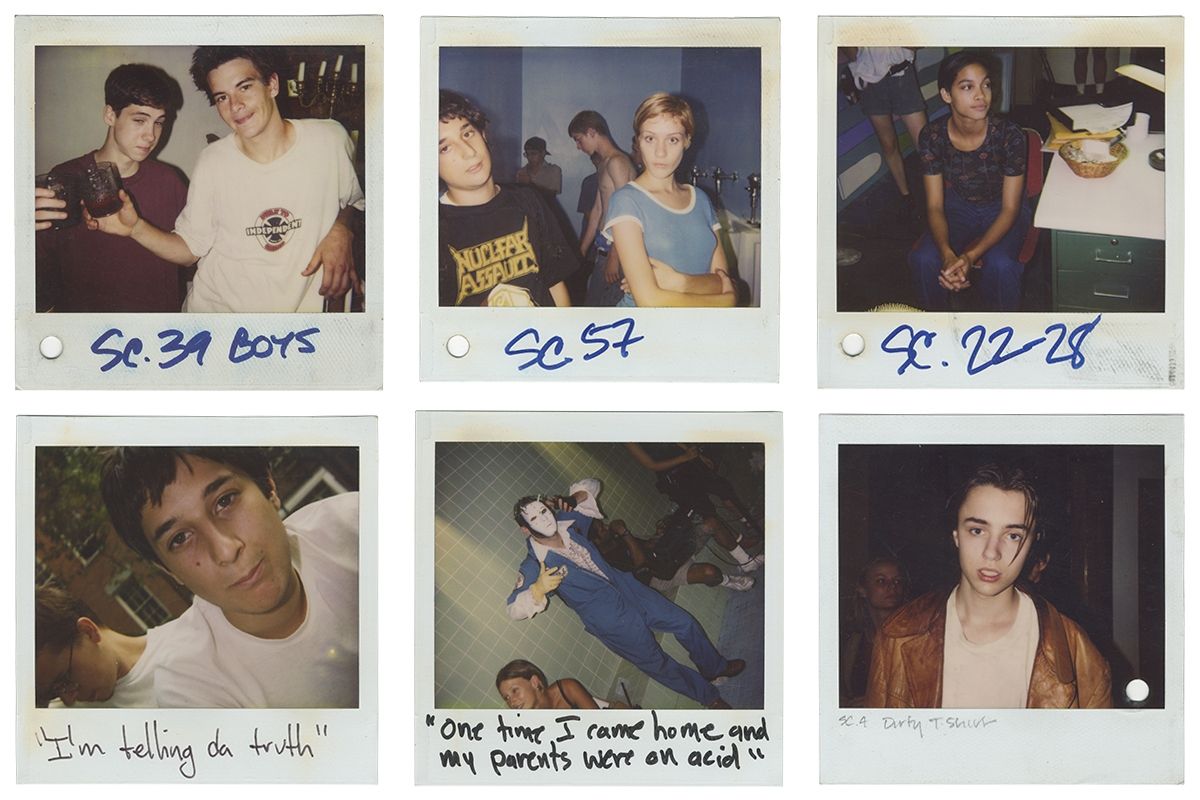

The two stories are so intertwined that four of the skaters from Supreme's original crew: Gio Estevez, Peter Bici, Mike Hernandez, and Justin Pierce all appear in the film. This is because they were all friends of Harmony, who moved to New York from Nashville after graduating to attend a creative writing course at New York University, went skateboarding, spent time going around aimlessly, sleeping on the roofs of the Big Apple with them. They were his friends, those same friends who inspired - Harmony wrote "simply" the truth of what was going on while he was out with the boys - the script of the film, written in 10 days, had only one single draft. And in fact, the film is immediate, direct, strong and simple at the same time speaks in an almost documentary style as it tells the harsh reality of which Korine and the others were protagonists.

The film shows a typical day around a group of teenagers addicted to alcohol, drugs, unprotected sex, petty crime, violence and the impending shadow of AIDS.

Director Larry Clark was fascinated by those guys who went around like "stray dogs" and with his Leica camera tried to capture pieces of their lives. The boys didn't like adults but with Larry it was different. Clark thought their way of dealing with life was cool and worth telling and there was a moment that changed everyone's life: Larry one day sat down next to Harmony and told him he wanted to make a movie and Harmony said that he too wanted to make a film.

At that point Clark realized that the only way to make the film truly authentic was to have it written by those who lived that way every day and knew every situation, every facet and above all the language - a fundamental element that Bondaroff also mentioned in the preface of the book "Supreme: Downtown New York Skate Culture" published by Rizzoli New York.

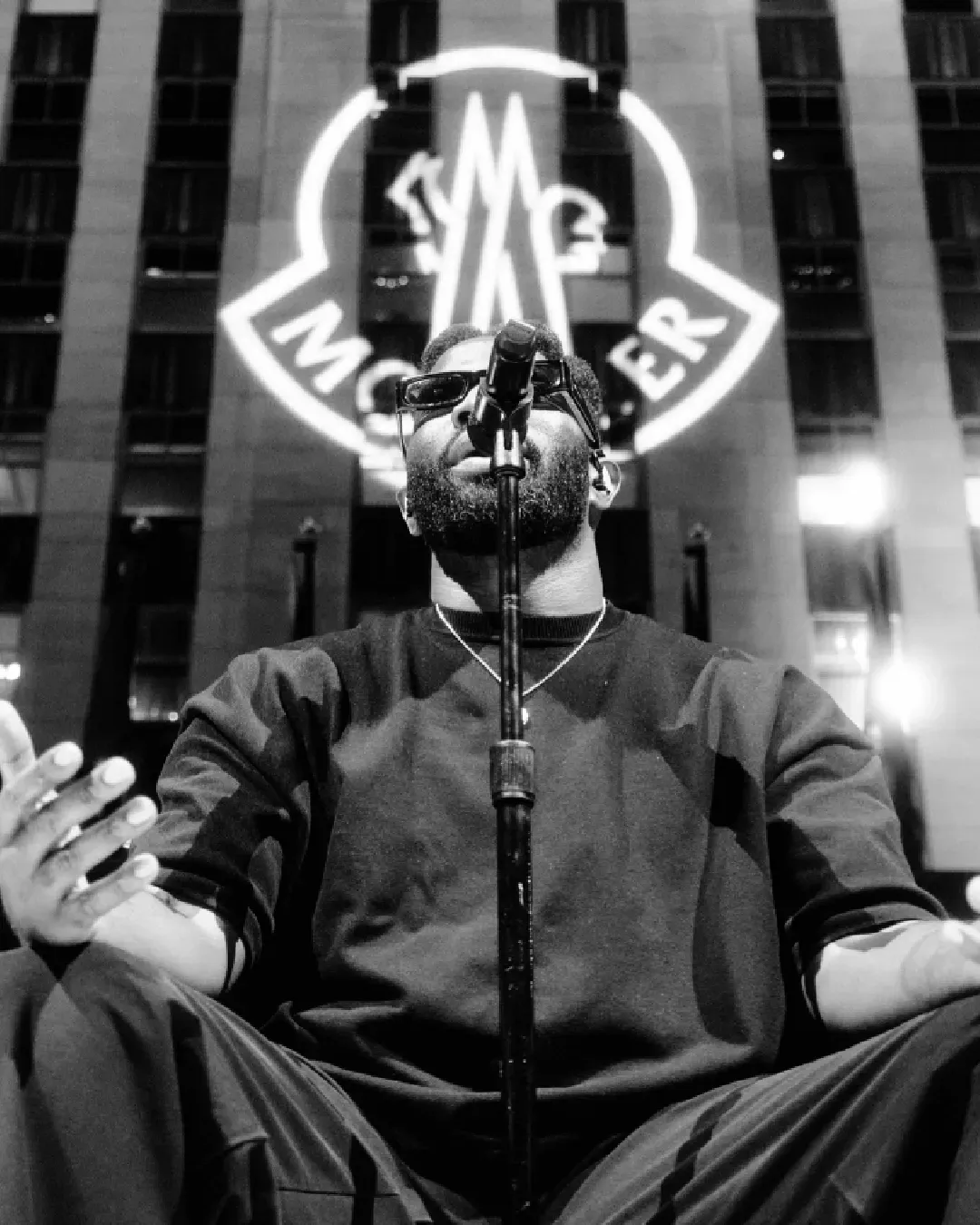

The 90s in New York were a big cauldron where countercultures were born and proliferated thanks to the randomness and confusion of the moment. The Wednesday night parties at the Funkmaster Flex Tunnel were great events. The most important hip-hop parties of the city where skaters, artists, photographers, musicians, rappers, met, mingled and influenced each other. The aesthetics of Supreme and "Kids" is, in fact, the result of all these ingredients.

Filming began in 1994 when James Jebbia opened the first Supreme shop in Lafayette. That was not just a shop, as I tried to explain before, it was an authentic place - as well as the script of the film - all the items for sale were arranged all around the shop and the center was empty so that you could enter with the skateboard. In 1995 that store was the subject of an interesting article by Vogue that tried to compare the Chanel store to 57 Fifth Avenue and that new skate shop in Downtown that had caught the attention of the whole city and that would soon have conditioned the streetwear world with a devastating impact that no one had foreseen.

I previously spoke about the constant anger of teenagers during that time, who more or less manifested this intolerance towards the world by finding ways to calm down from listening to music, to doing sport, studying, playing an instruments or simply growing up. I felt that anger, as many teenagers around the world felt it, and I tried it in the same years and at the same age as those kids who massacred their skateboards in the mid-1990s. I tried to do the same, in a different but difficult context, in the same way, that of the southern Italian province which at the time and still takes so much and returns little. I put on my baggy jeans, my airwalk, my Independent T-shirts and tried to imitate what they really did.