In what sense did they discover a “new color” in California? Let's say it exists - too bad you can't see it with the naked eye

At the University of Berkeley, California, a group of scientists has discovered what is described as a completely new color that does not exist in nature and, for now, cannot be recreated outside the laboratory. Named “olo”, this new color is an incredibly saturated blue-green hue, visible only under very specific conditions thanks to sophisticated laser technology. Although it may sound like science fiction, this discovery is the result of years of research on human vision and a meticulous experiment conducted on a limited number of selected subjects. The discovery, recently published in the journal Science Advances, stemmed from a question about the human retina: what would happen if the cells responsible for “seeing” color were stimulated in isolation? Under natural conditions, these cells, called “cones”, are never stimulated alone but work together. There are three types: S-cones for blue, M-cones for green, and L-cones for red. The interaction between these cones produces the full spectrum of colors we perceive. But thanks to a device called Oz, researchers were able to stimulate only the M-cones in isolation, thus avoiding the usual color blending that characterizes our vision. The result was a visual anomaly. All five participants in the study—three of whom were researchers involved—reported seeing a blue-green hue so intense that it resembled nothing found in nature, which was named “olo”. Participants were asked to compare olo to the most saturated teal possible using conventional light. To match the same intensity, olo had to be desaturated with white light, confirming its exceptional intensity compared to known colors.

Ren Ng, co-author of the study and also a subject of the experiment, described the experience to The Guardian as living for years seeing only pastel pink, and then, all of a sudden, seeing red for the first time—the same color family, but a completely different intensity. Despite the excitement, not everyone agrees that olo is truly a new color. Some scholars argue that it is rather an extremely intense variant of an already existing color, achievable only under very precise artificial conditions. But that is precisely the point: the discovery is not only about what olo is, but how flexible the limits of human visual perception can be. The implications of this discovery are not limited to theory. Even though the technology to reproduce olo outside the lab does not yet exist, researchers are optimistic that future developments in display technology may one day make experiences similar to olo possible on screens, in virtual reality, in design, and in digital art. Meanwhile, as explained on WWD, another line of research linked to the University of Berkeley explores tetrachromacy, a rare visual condition in which a person has four types of retinal cones instead of the usual three. This potentially allows them to distinguish hundreds of millions more colors than average. The team is looking for ways to make these new tones reproducible as well, for example in printing or display technologies.

What if some colors are invisible not because they’re rare, but because we physically can’t see them?

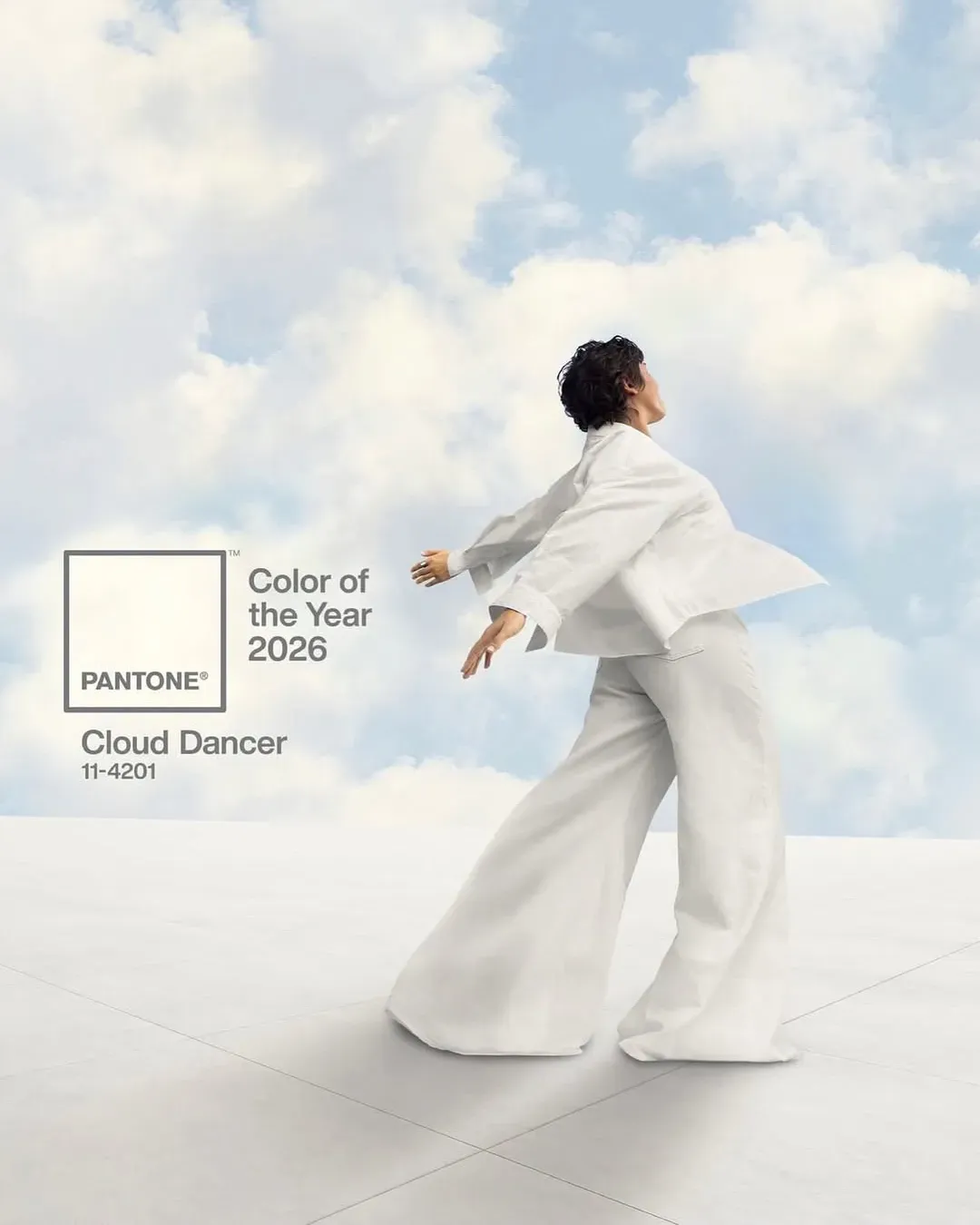

— PANTONE (@pantone) April 23, 2025

UC Berkeley scientists discovered Olo - a hue that can’t be rendered, only experienced.

Olo may never join the Pantone Color System… or will it?https://t.co/sBRGVhw85g pic.twitter.com/rxmbutd7y2

Interviewed about it by WWD, Leatrice Eiseman, Executive Director of the Pantone Color Institute, noted how the mere idea of a new color can spark great media and cultural interest. Although she has not seen olo firsthand, the director predicted that the concept will draw attention to the most saturated blue-greens already existing in the Pantone range and that the current fascination with space exploration could strengthen the connection between colors like olo and the imagery of the cosmos. Eiseman also said that olo may represent this kind of futuristic aspiration because, for now, it embodies what we can only imagine but not yet see. It remains to be seen whether the discovery of this new, peculiar shade will be translated into a realm where the public can actually interact with it or, in other words, whether this discovery will have a real cultural impact or will remain a fascinating and curious chapter in the advancement of optical science.