Was it an “orientalist” fashion month? In times of crisis, luxury industry winks at South and West Asian markets

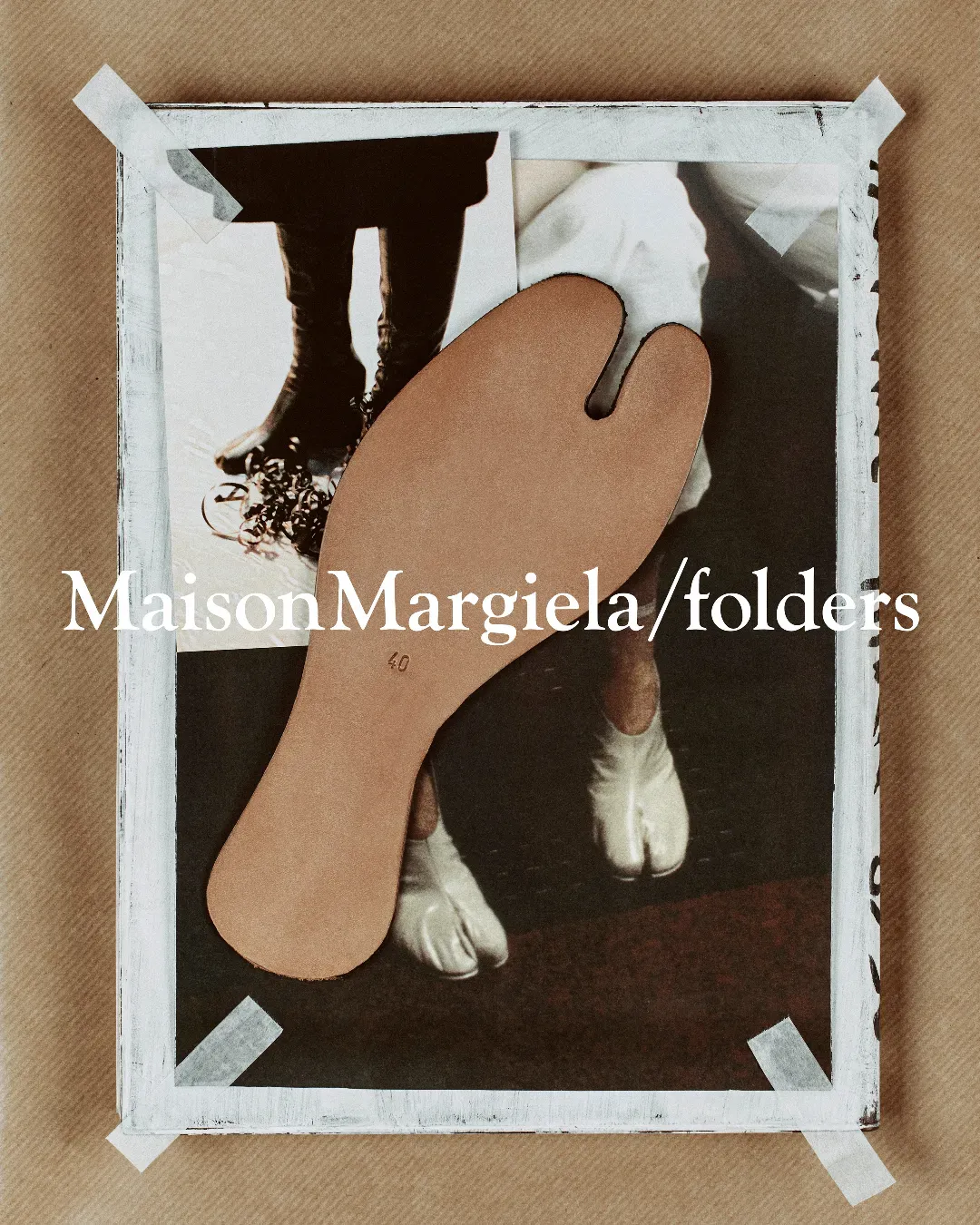

In literature, painting, and music, the term “orientalism” describes a certain attitude that Europeans have held for centuries toward Asian countries, which superficially manifests as an aesthetic fascination with a highly stereotyped concept of the “Orient,” where vastly different cultures and national identities are mistakenly grouped together. As defined in the 1970s by scholar Edward Said, it refers to ideological constructs that, through aestheticization, reproduce the opposition between a civilized world and a barbaric one, trivializing and misrepresenting the cultures they claim to portray. This term resurfaced during the last fashion month, between Milan and Paris, due to the apparent proliferation in various shows of design elements clearly referencing the traditional costumes of several South and West Asian countries — crucially, the same countries that luxury fashion, seeking alternatives to the Chinese market, is now trying to seduce, with India and the Arabian Peninsula leading the way, followed by Southeast Asian nations like Thailand and Indonesia. The issue became particularly notable in the case of Prada, which, despite presenting a mostly neutral collection, faced protests from an Indian artisan association after showcasing a very expensive sandal that was nearly identical to the traditional Kolhapuri sandal. The protest expanded to include Sambhaji Chhatrapati, a former MP and member of the ancient royal family of the Kolhapur region, who called it «new age colonialism», and the matter reached the country's main national media outlets. Official apologies soon followed, in the form of a formal letter to the Maharashtra Chamber of Commerce signed by the Group's heir, Lorenzo Bertelli. But as mentioned, it was an isolated case in a season where vague and cautious references to traditional designs from various Asian countries appeared throughout the looks.

.@Prada responds to the Kolhapuri chappal controversy, acknowledging that the sandals were inspired by traditional Indian footwear. The luxury brand said it is in contact with the Maharashtra Chamber of Commerce, Industry & Agriculture on this topic. pic.twitter.com/pha8qbb03M

— Apoorva Mittal (@Appy2209) June 28, 2025

Before analyzing how many and which references appeared, it is important to note that nearly every brand remained extremely cautious, limiting themselves to subtle allusions without ever crossing into outright appropriation — something that would surely have been called out by those concerned. Brands like Zegna and Louis Vuitton, for instance, cited as seasonal inspirations respectively «the scorching sun and heat of Dubai» and «the multifaceted sensibility of contemporary Indian tailoring: fabrics, cuts, colors, and craftsmanship shaped by a connection to the city, nature, and the vitality of the sun». The collections of both brands, with great sensitivity, did not seek to imitate the costumes of those reference countries but rather to evoke their atmospheres and colors — nonetheless, the Nehru shirts by Zegna, the bags inspired by The Darjeeling Limited by Louis Vuitton, and the pajama stripes (let us not forget that “pajama” is a word of Persian origin) featured in their collections and others, seemed like an attempt at a direct dialogue with audiences from the Indian and Arabian peninsulas.

Elsewhere, at IM Man but also at Emporio Armani, Qasimi, and once again at Prada, there were long, collarless shirts that resembled remixed versions of the classic Indian Kurta, while at Jacquemus, some looks evoked the combination of thawb tunics and taqiyah caps commonly seen in Gulf countries. At Bluemarble, more traditional caftans were featured. In Valentino's Resort 2026 collection, there was a kind of suede djellaba, which reappeared through a series of blouses that, paired with vests featuring geometric decorations, vaguely recalled a mix of Indian fashion and Bedouin costumes. At Dries Van Noten, there were colorful sashes around the waist reminiscent of the fabric hizams used in Yemen to hold traditional jambiya daggers, or the zonnar; and in the same show, there were also large, richly decorated fabric rectangles similar to sarongs, also seen in Junya Watanabe's show, which - along with Walter Van Beirendonck - included, for example, long men’s tunics.

If we can speak of “orientalism,” it is precisely because all these various design touches (be they collars, scarves worn like sarongs, tunic-shirts layered over trousers, or blouse-and-printed-vest combos) seem to evoke a vague and distant horizon—almost that faraway, mythological, and imaginary land that Victorian writers referred to with the erroneous and colonial term “the Orient”: a world where the distinctions between Indian, Southeast Asian, North African, and Arab inspirations blur and flatten into something different and equidistant from all the cultures of origin. Is it copying, a respectful homage, or a brazen seduction? Let future generations be the judge. More than colonialism or post-colonialism, however, one might speak of globalism: these garments, which seem to wink at an ambiguous and composite audience, are not turning national dress into “costumes” but are attempting to create a global wardrobe where the Italian suit, the biker leather jacket, sneakers, or leather lace-ups coexist in a syncretic vortex meant to serve, without distinction, all customers around the world and also to maximize the media impact of runway shows presented to a global audience who will recognize some of the silhouettes without conceptual inconsistencies between fashion that is “Made in Italy” and one with “worldwide distribution.” At the very least, we can say that the brands’ choices reveal their anxieties: will it be possible to find new room for growth in Asia to fuel the expansion of a stalled system?