A few days ago, to the surprise of many, Bally ended his collaboration with Rhuigi Villaseñor in what looked like an amicable termination of the joint relationship. The peculiarity of the affair lies not so much in the news itself (we are now used to unexpected farewells from creative directors) as in the speed with which the brand and the designer decided to say goodbye. Just a year and a half after his appointment, Rhude's founder said goodbye to the Swiss brand, leaving behind two shows presented during Milan Fashion Week and little else. Rhuigi's departure is just the latest in a long line of farewells that make the question of how much a brand needs a creative director at its helm more topical than ever. In today's fashion world, where people fight over a place on the front page of industry websites, a creative director is certainly a means of keeping attention for a brand high, a media catalyst who can fill the role of front man in a world where teamwork seems to be frowned upon. On the other hand, the creative director is also the one who has to balance the two souls that drive a brand, the artistic and the commercial. Not everyone has broad enough shoulders to carry the burden of such a task and balance values such as heritage, creativity, but also the desirability of one's own work without sinking into the abyss of creative apathy. If the figure of the creative director has become increasingly complex and unstable than in the past, one wonders to what extent it is really a necessity to have one, to which every brand must surrender, and whether it is not in some way the result of a madness born of what fashion is today.

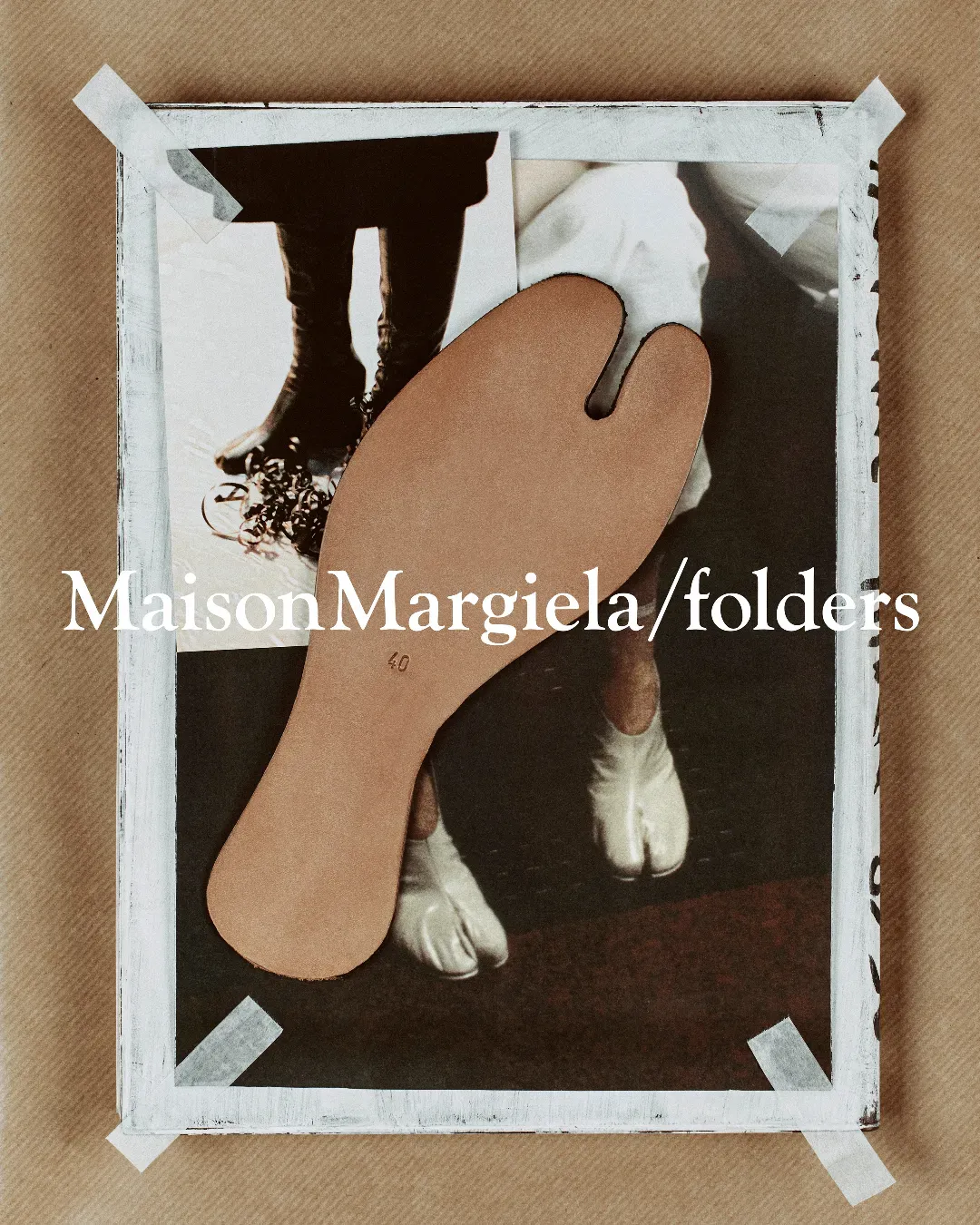

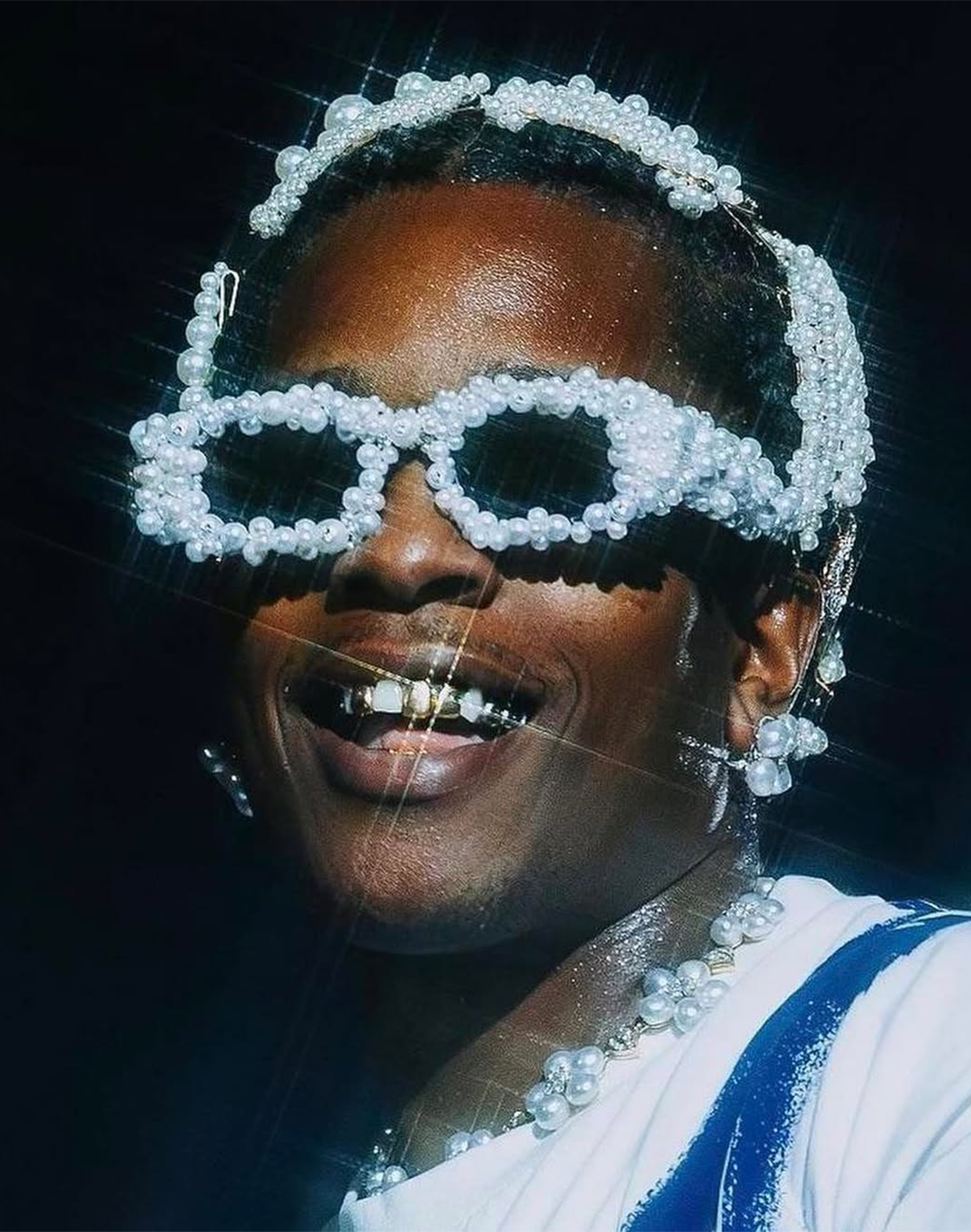

Perhaps it was Lanvin who, a few weeks ago, bade farewell to Bruno Sialelli by announcing an interregnum period during which, among other things, Lanvin Lab will be inaugurated, a project that will involve talents from all over the world as creative partners who could resemble guest designers in some ways. Something similar has also been done by Louis Vuitton, which, before announcing Pharrell Williams as Virgil Abloh's heir, first entrusted the menswear reins to the brand's creative team and then hosted KidSuper as guest designer for a collection presented in Paris. On the other hand, the very choice of Williams as artistic director is proof of how the LVMH brand has also chosen not to rely on a designer in its most classic form, but rather on a name capable more of catalysing media attention than of sewing a dress. Looking back then, the examples of creative co-management within a brand are numerous, from the most recent imposed by force majeure to those that have become part of a brand's history. Gucci, for example, in the period of transition between Alessandro Michele and Sabato De Sarno, relied on the creative team of the brand that led it until a few days ago, while Maison Margiela from 2009 to 2014 did not have a real creative director in homage to the philosophy of anonymity that the founder had pursued throughout his career. The same for Ann Demeulemeester, which from the acquisition of Claudio Antonioli until the appointment of Ludovic de Saint Sernin last December had relied solely on the in-house design team, but above all for Bally, which before Rhuigi Villaseñor had produced collections collectively for several years.

There are many examples, many of them successful, like that of Loro Piana, which had stressed last March through the mouth of its CEO Damien Bertrand that the brand did not need to choose a creative director, despite some rumours pointing to this or that name. «Loro Piana has never had a creative director, so I do not think it's necessary at the moment because the definition of the silhouette has already changed» Bertrand had said, stressing that some brands have the luxury of continuing their work freely without necessarily looking for that knockout punch to bring to the catwalk. After all, why should the buyer of a brand that has gone for years without creative direction care about the name that designs the collection? History is full of realities that could break free from the pressures of the fashion system, but instead continue to fall into something that increasingly resembles an exercise in self-destruction. What we can still ask ourselves today is how many more wrong decisions are needed before we make a decisive one.