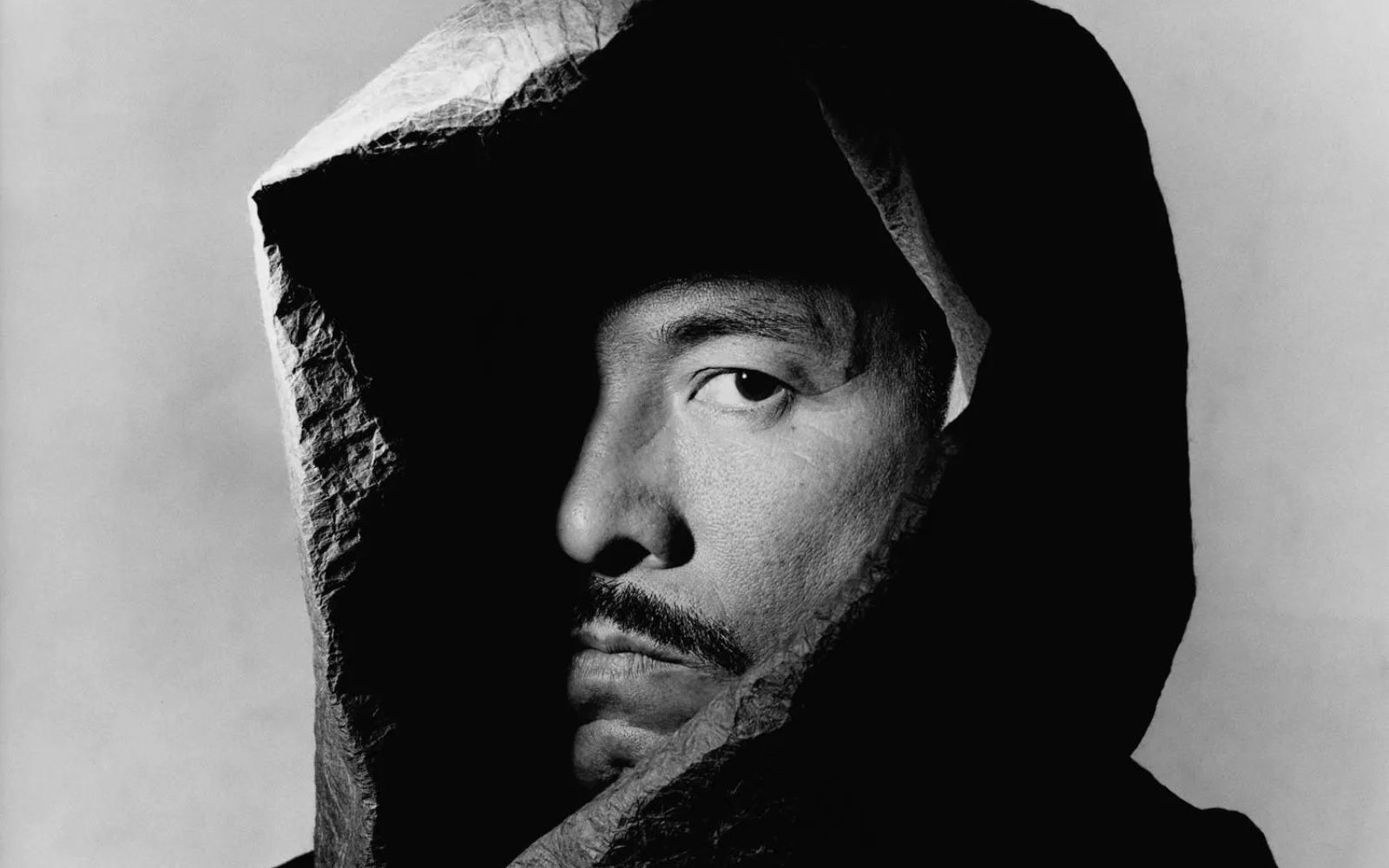

Issey Miyake's cult of pleats He was the wind tailor who wrote the history of fashion

He passed away on August 5, Issey Miyake, in a Tokyo hospital from cancer he had been battling for some time. He pioneered a stylistic vision that translated his thinking into a flowing, concrete aesthetic, combining heritage and hi-tech in recognizable fabrics such as pleating, and was able to maintain a constant sense of balance between avant-garde tailoring, Eastern tradition, and technological experimentation. Shapes and materials were his obsession: even before studying reality in its aesthetic aspects, Issey Miyake was interested in understanding how it works.

An architect's soul with a cult for folds so ingrained that he trained all materials in clothes where the continuous experimentation with geometries and colors was the poetic manifesto of structural minimalism that gave him the title of artist. Even after he left the creative direction of his lines, his supervision ensured an aesthetic cohesion paradigmatic of an approach in which opposites attract and resolve into an inimitable style. The matter was his tabula rasa, the script that allowed him to investigate the relationships between body and dress. He inaugurated a new modeling concept called A-Poc (A piece of cloth), a Spartan theory that it was necessary to use a single piece of fabric to wrap around the body, adapting to movements and transforming accordingly. For Issey Miyake, clothes were pure metamorphosis.

Folding, crumpling, crisscrossing, but most of all pleating: making garments wrapped in small close folds recreating an accordion effect resist the laws of physics. He used a poor fabric such as polyester that, folded with hot presses, guaranteed indestructible performance to pants, pencil skirts, and dresses. This idea of material (im)perfection became the manifesto of his ready-to-wear line in 1993, Pleats please by Issey Miyake, whose poetics found natural ambassadors in dancers and gymnasts. Issey Miyake had succeeded in creating for himself a legion of loyal followers by proposing a form of brutal minimalism that had quite spontaneously broken down boundaries such as gender and seasonality. Not that the importance of the archive, heritage, and contamination had escaped him: his Tebori-designed shirts, a Japanese tattoo-like technique, and his Sashiko-decorated dresses enchanted Vogue USA and Bloomingdale's. The rest is the story of a tailor, an architect, a designer, and a businessman who, while having an elective affinity for the air, remained firmly on the ground.