Nigo has already changed Kenzo The return of a Japanese designer to the brand was a return to form for its aesthetics

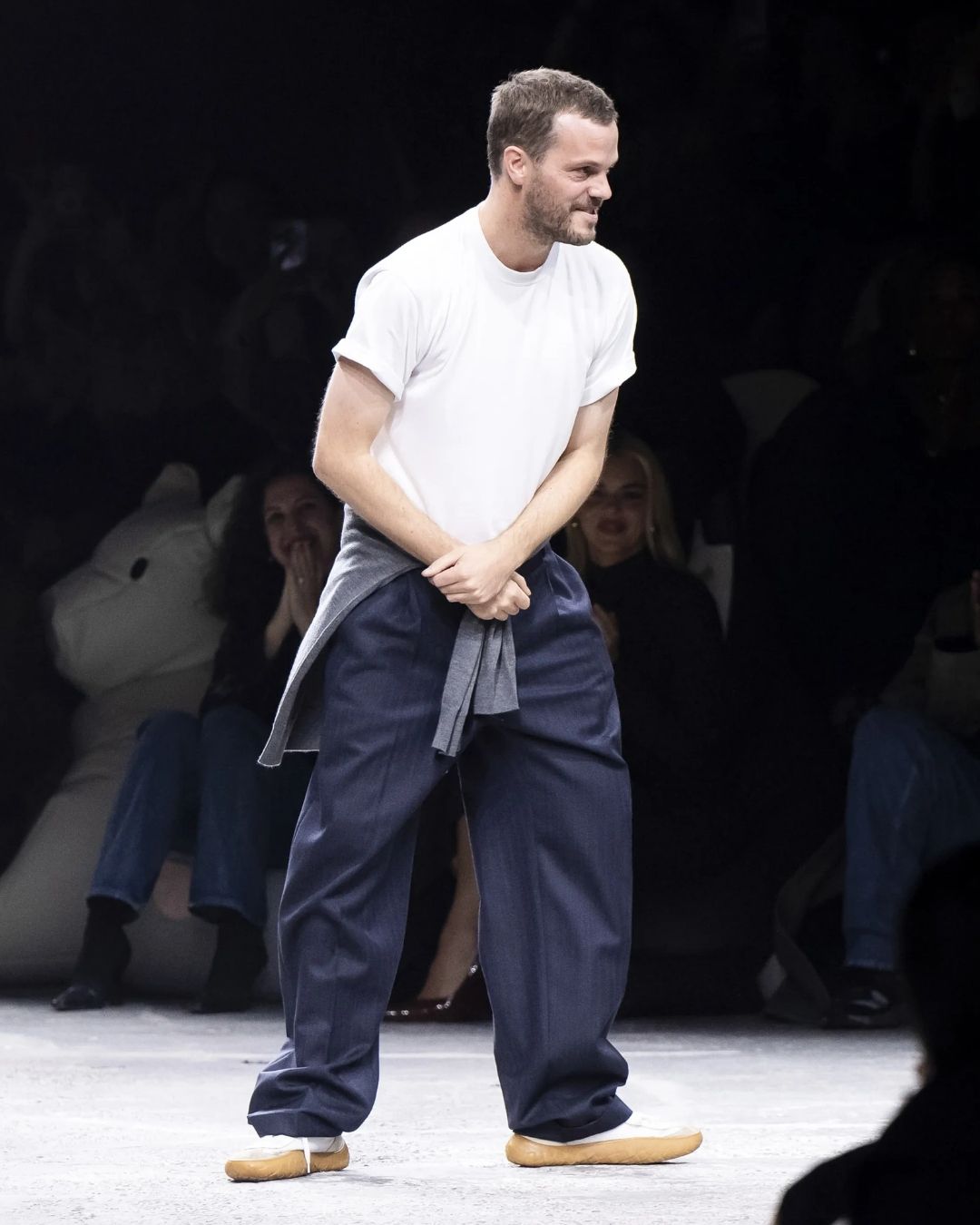

Kenzo is a historic brand and much loved by fashion insiders, especially the one that still remembers the shows organized by the founder Kenzo Takada during the 80s. A legacy that had been lost over time: since 1999, Takada had handed over the creative helm first to Gilles Rosier and Roy Krejberg, then to Antonio Marras until 2011, to Humberto Leon and Carol Lim until 2018 and to Felipe Oliveira Baptista from 2019 until last April. Such a frenetic series of changes of hands that had in fact completely altered the aesthetic language of the brand, which was kept commercially afloat thanks to branded items, perfumes and accessories, but whose identity many had progressively forgotten. For this reason, the announcement that Nigo would be the new creative director of the brand was greeted with great expectation: Nigo is a cultural force, cult designer founder of cult labels, alumnus of the Bunka Fashion College just like Takada, collector of the latter's designs and friend of half of the elite of the hip-hop world. And his collection presented yesterday at the Galerie Vivienne in Paris, location of Takada's very first boutique in Paris, was one of the best shows of the season – a show devoid of particular sartorial acrobatics, but which made a necessary tabula rasa of the past and paved the way for the brand towards the future.

The most interesting part of the collection seen yesterday was the clash of archive, preppy aesthetics and references to Japanese tradition such as haori jackets. The combination has returned the effect of a clean slate arrived after the very artistic works but little in dialogue with the audience of Baptista and above all with the hyper-popular aesthetic, both for better and for worse, of Leon and Lim. Yesterday afternoon they paraded suits, overalls, jeans, sweaters, caps, skirts. All quite practical and everyday items, in some cases also classic-looking but enlivened with the right amount of cultural contamination, capricious inspiration of graphics and details and a gentle wit: from the nonchalant fit of the suits, to the soft but very meticulous formality of the total denim looks, passing through the floral prints designed by Japanese potters and that sense of order and logical sense that also dominates patchwork clothes, there is originality everywhere but also a sense of quiet discretion. Everywhere you can feel the aroma of nostalgia: as Nigo reread the hip-hop culture to build BAPE, now he rereads the '68 French and the vintage world of American aesthetics to build the new Kenzo.

The wide silhouette of the suit and that of the mod uniform revived by color blocking, mixes with the sloping silhouette of the haori jackets - always the haori, converted into blazer, adds a touch of inspiration to the classic suit. The logo becomes a shy little flower, located on the buttons, on the hem of the jackets - infinitely more discreet but also more precious, less shouted. It is the return to the form of a brand that needed just to change one single thing: a creative director-star who could find the center of its aesthetics again and wear with ease and credibility Takada's mantle and his cultural legacy, bringing a concrete vision rooted in reality. After all, the very charm of Kenzo lies in his vision of multiculturalism which, in one way or another, must be part of the brand's connotations not in the form of easy exoticism but of an encounter between different cultures from which the spark of innovation and originality is produced.

Nigo's greatest achievement as creative director of Kenzo has been in part but will be in the future to cancel the last twenty years of the brand not so much to bury them as more to bring to light what was there before. It's no mystery that Kenzo's famous tiger sweater presented during the brand's FW12 show helped the brand stay alive in the years of streetwear-mania. A commercial blessing for which a Faustian price was paid: for a gigantic part of the public that had never known Takada's creations, the entire brand was reduced to a logoed sweatshirt that, once the novelty factor was exhausted, still remained alien to both the streetwear and luxury discourse. A heritage that had had a breakthrough with Baptista, an honest and talented designer, but that could really be resurrected by a successor to Takada who would guarantee a more solid continuity with the past and, ultimately, a concrete credibility and authenticity that the sweatshirts logoed with the tiger had buried as a year ago.